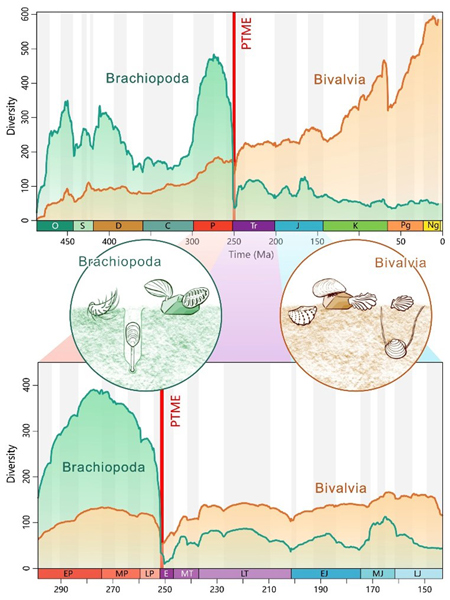

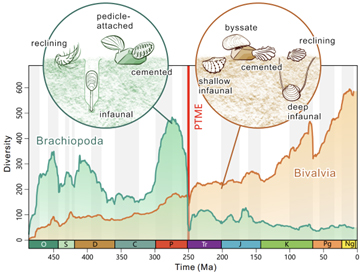

Scientists have used complex statistical analysis to assess one of the most dramatic changes in the history of visible life on Earth. At the end of the Permian, during a mass extinction event there was a dramatic and extensive faunal turnover between brachiopods and bivalves.

One of the biggest crises in Earth’s history was marked by a revolution in the shellfish. Brachiopods, sometimes called “lamp shells”, as some genera superficially resembled Roman lamps, were replaced everywhere ecologically by the bivalves, such as clams, mussels and oysters. This happened as a result of the devastating end-Permian mass extinction which reset the evolution of life 250 million years ago.

Research conducted by palaeontologists based in Wuhan (China) and the University of Bristol, has shed new light on this crucial faunal turnover when ocean ecosystems changed, eventually taking on a more modern, familiar structure that still persists today.

Brachiopods and Bivalves

Life on land and in the sea is rich and forms particular ecosystems. In modern oceans, the seabed is dominated by animals such as bivalves, corals, gastropods, crustaceans, marine worms and fishes. These ecosystems all date back to the Triassic when life slowly recovered from the “Great Dying”. During that crisis, only one in twenty species survived, and there has been long debate about how the new ecosystems were constructed and why some groups survived, and others perished.

Brachiopods were the dominant shelled animals prior to the extinction. However, bivalves thrived afterwards, seemingly better adapting to their new conditions.

Lead author of the study published in “Nature Communications”, Zhen Guo commented:

“A classic case has been the replacement of brachiopods by bivalves. Palaeontologists used to say that the bivalves were better competitors and so beat the brachiopods somehow during this crisis time. There is no doubt that brachiopods were the major group of shelled animals before the extinction, and bivalves took over after.”

Statistical Bayesian Analysis

Co-author Joe Flannery-Sutherland added:

“We wanted to explore the interactions between brachiopods and bivalves through their long history and especially around the Permian-Triassic handover period. So, we decided to use a computational method called Bayesian analysis to calculate rates of origination, extinction, and fossil preservation, as well as testing whether the brachiopods and bivalves interacted with each other. For example, did the rise of bivalves cause the decline of brachiopods?”

The researchers found that in fact both groups shared similar trends in diversification dynamics right through the time of global crisis.

This suggests that these two groups were not really competing or preying on each other. It is more likely that these unrelated groups were responding to similar external drivers such as fluctuations in sea temperature, oxygen levels and acidity.

The bivalves eventually prevailed, and the brachiopods retreated to deeper waters, where they still occur, but in much reduced numbers.

Statistical Analysis to Resolve the Brachiopods and Bivalves Faunal Turnover Issue

Professor Zhong-Qiang Chen (China University of Geosciences, Wuhan) explained that it was very satisfying to see how modern computational techniques helped resolve a long-standing issue in palaeontology.

Professor Zhong-Qiang Chen stated:

“We always thought that the end-Permian mass extinction marked the end of the brachiopods and that was that. But it seems that both brachiopods and bivalves were hit hard by the crisis, and both recovered in the Triassic, but the bivalves could adapt better to high ocean temperatures. So, this gave them the edge, and after the Jurassic, they just rocketed in numbers, and the brachiopods didn’t do much.”

Fossils of over 330,000 brachiopods and bivalves were analysed in the course of this study. The Bristol University supercomputer took weeks to crunch all the numbers. The Bayesian analysis took into account all kinds of uncertainties and aspects of the data to provide an extremely detailed report on the evolutionary changes.

Professor Michael Benton (University of Bristol) concluded:

“The end-Permian mass extinction was the biggest of all time, and it massively reset evolution. In fact the 50 million years after the crisis, the Triassic, marked a revolution in life on land and in the sea. Understanding just how life could come back from near-annihilation and then set the basis for modern ecosystems is one of the big questions in macroevolution. I’m sure we haven’t said the last word here though!”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bristol in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Bayesian analyses indicate bivalves did not drive the downfall of brachiopods following the Permian-Triassic mass extinction” by Zhen Guo, Joseph T. Flannery-Sutherland, Michael J. Benton, and Zhong-Qiang Chen published in Nature Communications.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment