Scientists Suggest “Wing Feathers” Evolved for Courtship

A new study into the fossilised bones of “bird mimic” dinosaurs, a clade of the Dinosauria known as the ornithomimids, by a team of scientists based in Canada has revealed that these dinosaurs too were covered in feathers, just like their maniraptoran cousins. However, the study which examined the fossils of juveniles as well as adults has concluded that wing feather-like structures are only to be found in older, more mature specimens. This suggests that wing feathers may have evolved in some types of dinosaur to assist in courtship displays to find a mate.

Feathers on Ornithomimid Dinosaurs

The ornithomimids (bird mimics) are a group of Cretaceous theropod dinosaurs known from the Northern Hemisphere (North America and Asia). They were named ornithomimids, not because scientists first thought that these reptiles were feathered, but from anatomical studies of their fossilised bones it was clear that these dinosaurs shared a lot of common features with modern ground dwelling birds. They had lightly built skeletons, light bones and as a group they tended to have small skulls, beaks but with jaws mostly lacking teeth, long legs and long tails.

Although ornithomimids had similar body plans individual genera are distinguished by differences in their beaks, the size of the arms and hands and their body proportions. Deinocheirus (Deinocheirus mirificus) is believed to have been a member of the ornithomimids – the largest discovered to date with some palaeontologists estimating this animal to have been about the size of a Tyrannnosaurus rex.

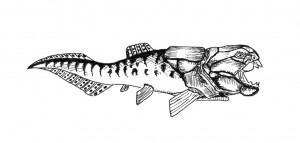

Feathered Ornithomimid – Deinocheirus

Giant, winged theropod.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

A Collaboration Between Scientists

The study, a collaboration between scientists at the University of Calgary and the Royal Tyrrell Museum, both in Alberta, Canada, suggests that feathers associated with dinosaur fossils may actually be found in strata that was previously thought to be too coarse grained to preserve delicate structures such as the filaments from primitive feather-like structures.

Palaeontologists François Therrien (curator at the Royal Tyrrell Museum) and Darla Zelenitsky (University of Calgary) studied a series of Ornithomimus fossils that had been found in Upper Cretaceous strata exposed in the Canadian Province. Ornithomimus was first named and described by the American palaeontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1890.

A number of species are associated with this genus and Ornithomimus seems to have been a particularly widespread ornithomimid with fossils having been discovered all over the western part of North America, from Alberta in the North to Texas in the south. The particular Ornithomimus fossils studied by the Canadian scientists come from the Badlands of Alberta and date from approximately 75 million years ago (Campanian faunal stage).

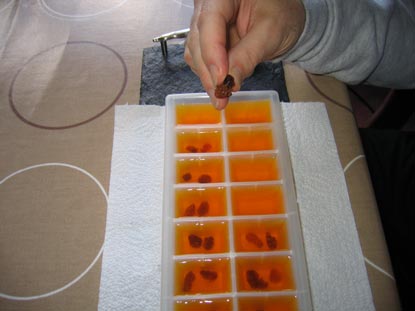

The specimens studied included a juvenile and two adult skeletons preserved in a sandstone deposit. Although the fossils had been known for many years, it was only recently the evidence of feathers was found after the fossil material was subjected to intense analysis using ultra violet light scans and computerised tomography.

It had long been suspected that ornithomimids were covered in downy, insulating feathers but this is the first time that feathered dinosaur specimens have been found in the western hemisphere. The discovery of the feathers re-affirms earlier research that suggested that most if not all ornithomimids were covered in a coat of feathers.

Assistant Professor Darla Zelenitsky commented that this was “a really exciting discovery”. Although many different types of “bird-mimic” dinosaur are known these Canadian specimens are the first to reveal that ornithomimids were covered in feathers, just like other types of theropod dinosaur such as the Dromaeosaurs.

Parents with Wing-like Forearms in the Ornithomimidae

Mums and dads with wings in the Ornithomimidae.

Picture credit: Press Association (illustration by Julius Csotonyi)

Interestingly, the research team noted differences in the feathers between the juvenile and the adult animals. The mature, older individuals had developed larger feathers on their arms, these formed a wing-like structure but clearly adult Ornithomimus were too big to fly, with some specimens reaching over four metres in length.

Associate Professor Zelenitsky explained the significance of this finding by stating:

“This pattern differs from that seen in birds, where the wings generally develop very young, soon after hatching.”

The development of primordial wing structures in adult animals suggests that juveniles and sub-adults did not have these feathered structures on their arms until they had grown up and become old enough to mate and reproduce.

Therrien postulated that:

“The fact that wing-like forelimbs developed in more mature individuals suggests they were used only later in life, perhaps associated with reproductive behaviours like display or egg-brooding.”

The finding of evidence of fossilised feathers in sandstone rocks has potential implications for future discoveries of feathered dinosaurs in North America. Feathered dinosaurs are known from fine grained formations such as those from the Liaoning Province of China. The discovery of traces of feathers on dinosaurs excavated from sandstone, a very common fossil bearing sedimentary substrate suggests that a more detailed examination of existing fossil dinosaurs from sandstone deposits may reveal more signs of dinosaur plumage.

For models and replicas of ornithomimids and other theropod dinosaurs: CollectA Prehistoric Animals (Age of Dinosaurs Popular).

The ornithomimid specimens used in this study will be put on display as part of a larger exhibition on theropods at the Royal Tyrrell Museum. These fossils also indicate that primordial wing-like structures on the arms of dinosaurs evolved earlier than previously thought amongst non-maniraptoran theropods.

Although such structures were never intended for flight, a set of feathery arms would have helped an adult to brood a clutch of eggs, sheltering them and keeping them warm whilst the adult sat on the nest. Once the eggs had hatched than the feathery structures could act as a shade for the youngsters in the nest as well as providing warmth and shelter. If the family went on the move then the adult could use the feathered arms to signal to their offspring, part of the non-verbal communication between a parent and young.

The scientific paper: “Feathered Non-Avian Dinosaurs from North America Provide Insight into Wing Origins” by Darla K. Zelenitsky, François Therrien, Gregory M. Erickson, Christopher L. Debuhr, Yoshitsugu Kobayashi, David A. Eberth and Frank Hadfield published in Science.