Large Mammals with Small Brains Prone to Extinction

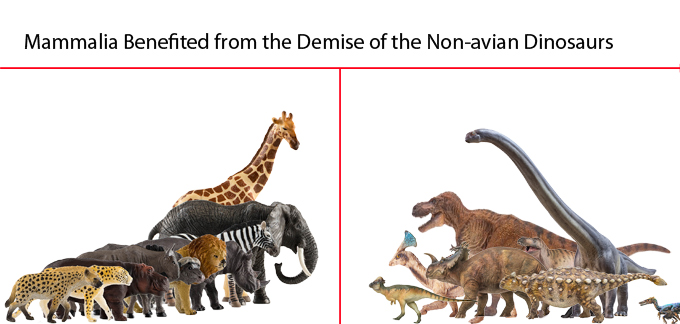

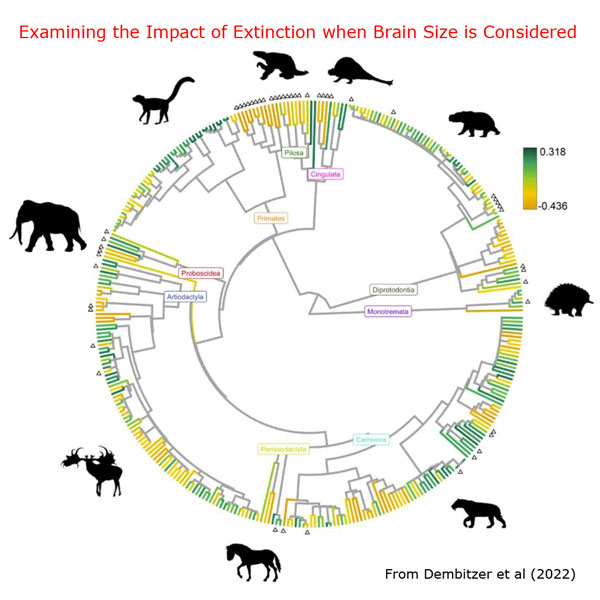

Scientists from the University of Tel Aviv in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Napoli have published a study that suggests having a small brain relative to your body size predisposed Late Quaternary mammals to extinction. If you were a “smart” mammal, with a relatively big brain in proportion to your body size, you were less likely to become extinct.

A soft toy Megatherium. The newly published research suggests that mammals with relatively small brains in proportion to their large bodies for example, many members of the Order Pilosa such as the ground sloths, were more likely to go extinct in the Late Quaternary.

The Extinction of Megafauna

The Late Quaternary is marked by a drastic global extinction event, mainly of large-bodied, land mammals. Causes proposed for these extinctions include overhunting by an increasing human population, particularly in areas such as the Americas and Oceania where modern humans had been largely absent previously. Earlier papers had proposed that species with traits that make them less prone to human hunting (arboreal, nocturnal, or forest dwelling) were more likely to survive.

However, the rapid decline and extinction of large, terrestrial animals is linked to the end of the last glacial period (25,000 to 12,000 years ago) which saw dramatic climate change. The research team hypothesised that the large mammals that survived the extinctions might have been endowed with larger brain sizes than those that perished. Larger brains might have helped these animals to adapt better and to cope with the wild fluctuations in climate.

To test this idea, the scientists assembled data on the brain size of 291 living mammal species plus 50 more that went extinct during the Late Quaternary.

The team found that models that used brain size in addition to body size predicted extinction status better than models that used only body size. It was concluded that possessing a large brain was an important, yet so far neglected and rarely studied characteristic of surviving megafauna species.

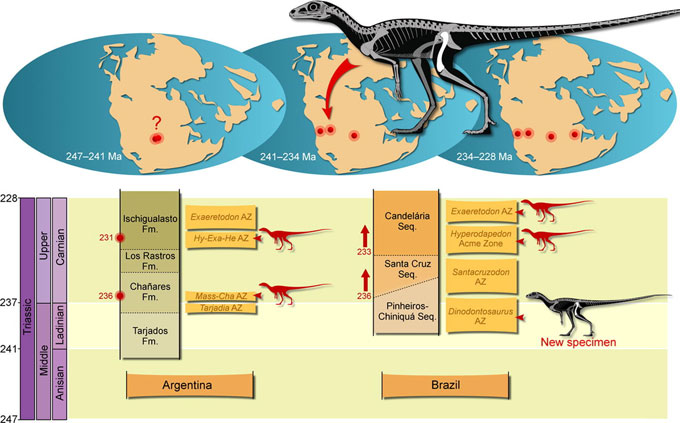

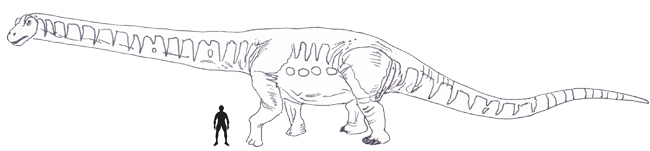

The phylogenetic tree used in the brains size relative to body size paper. Terminal branches are colored according to residuals of endocast volume versus body mass regression with order as a random effect (large brains: green; small brains: gold). Large mammals with proportionately large brains such as monkeys record a lower level of extinction compared to other types of mammal. Picture credit: Dembitzer et al.

Picture credit: Dembitzer et al

Implications for Large Mammals Living Today

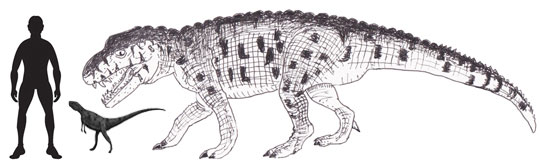

One prominent feature shared by many extinct taxa was their large body size. In mammals, body size is correlated with several traits, including low population density, small population size, long lifespans, extended gestation periods along with prolonged inter-birth intervals and low fecundity.

Brain size is strongly correlated with body size as well and yet, mammals of similar size can have greatly different brain sizes.

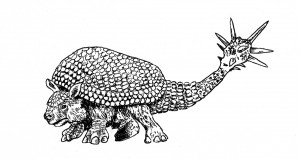

Members of small-brained orders may not have possessed the behavioural flexibility needed to cope with a changing climate and/or the arrival of Homo sapiens. Glyptodonts such as Doedicurus (order Cingulata), with their large bodies and small brains died out in the Late Quaternary. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

In studies of modern birds and mammals, large brains have been found to improve survivability as these animals can modify their behaviour and adapt to rapidly changing environments and new threats such as an expanding human population.

When considering which animals around today might be under the most severe threat of extinction, brain-size should be considered when calculating the risk factors.

The paper published as an open access document in “Scientific Reports”

The scientific paper: “Small brains predisposed Late Quaternary mammals to extinction” by Jacob Dembitzer, Silvia Castiglione, Pasquale Raia and Shai Meiri published in Scientific Reports.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Dinosaur Toys and Models.