200th Anniversary of the First Ichthyosaur Scientific Paper

This week saw the 200th anniversary of the first scientific description of an animal that was later named as an ichthyosaur. On June 23rd 1814, Sir Everard Home published the first account of the Lyme Regis ichthyosaur that had been found a few years earlier by the Anning family (Mary and her brother Joseph). The paper was published by the Royal Society of London, it had the catchy title of “Some Account of the Fossil Remains of an Animal More Nearly Allied to Fishes than any Other Classes of Animals”.

In the account, Sir Everard Home, an anatomist who held the distinguished position of Surgeon to the King, attempted to classify the fossilised remains of what we now know as a “Fish Lizard”. Reading the paper today, one can’t help but get a sense of utter confusion in the mind of the author.

Ichthyosaur

Sir Everard, had one or two secrets and although two hundred years later, it is difficult to place in context what was behind the paper, after all, at the height of the Napoleonic war there was intense rivalry between the French and English scientific establishments, an assessment of this work in 2014 does little to enhance Sir Everard’s academic reputation.

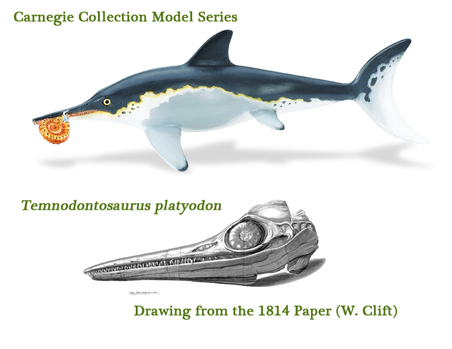

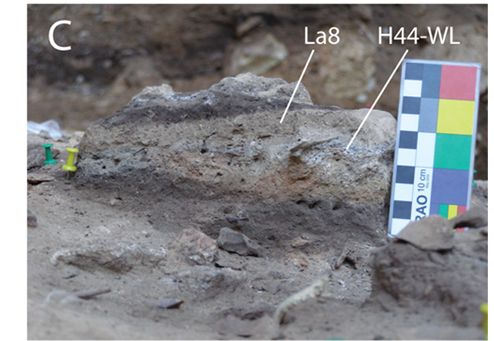

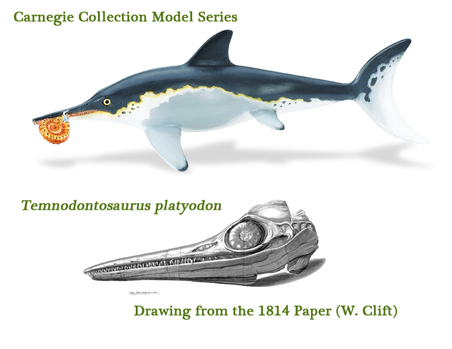

A Model of an Ichthyosaur and One of the Plate Illustrations from the Scientific Paper

The illustration from the paper and a model interpretation of a “Fish Lizard”.

Picture credit: Safari Ltd top and the Royal Society (William Clift) bottom

Back to those secrets. Whilst notable figures in the history of palaeontology such as the Reverend William Buckland was corresponding with Georges Cuvier, the French anatomist and widely regarded as “the founder of modern comparative anatomy”, against a back drop of war between Britain and France, in a bid to understand the strange petrified remains found on England’s Dorset coast, Sir Everard raced into print, to be the first to describe this creature. Just like today, if you are the first to do something than fame and fortune can await. Trouble is, Sir Everard, by a number of accounts, was relatively incompetent. He was also a cheat!

Nascent Palaeontology

In 1771, when the young Everard was a teenager, his sister married John Hunter, an extremely talented surgeon and anatomist who had already built a reputation for himself as being one of the most brilliant scientists of his day. He was able to learn a great deal from his brother-in-law and this coupled with his wealthy background soon propelled the ambitious Everard to the forefront of London society. However, the much older John Hunter died suddenly from a heart attack in 1793 and it has been said that Everard used his brother-in-laws untimely death to his distinct advantage.

Having removed “a cartload” of John Hunter’s unpublished manuscripts from the Royal College of Surgeons in London, Everard began publishing them but under his own name. This alleged plagiarism enhanced the young surgeon’s reputation and led to his steady rise in scientific circles, permitting Everard to gain the fame and good standing amongst his peers that he so craved. Such was his desire to keep his plagiarism a secret, that it is believed that he burnt Hunter’s original texts once they had been copied out. So enthusiastic was he to get rid of the evidence that on one occasion he set fire to his own house.

And so to the published account of the ichthyosaur. Sir Everard explained his willingness to examine the fossilised remains by writing:

“To examine such fossil bones, and to determine the class to which the animals belonged comes within the sphere of enquiry of the anatomist.”

Describing Fossil Remains

In the paper, Sir Everard describes the fossil remains in some detail, although his descriptions lack the academic rigour found in other papers later published by Cuvier, Mantell and Owen. The author states that the fossil material was found in the Blue Lias of the Dorset coast between Charmouth and Lyme Regis, the fossil discovery having been made after a cliff fall. The paper claims that the skull was found in 1812 with other fossils relating to this specimen found the following year. The role played by the Annings in this discovery is not mentioned by Home. This assertion itself, may be inaccurate.

Many accounts suggest it was Joseph Anning who found the four-foot-long skull in 1811, as to whether Mary was present at the time, we at Everything Dinosaur remain uncertain. Although Mary and Joseph together are credited by many sources for finding other fossil bones related to this specimen in 1812.

The potential mix up in dates, pales when the rest of Sir Everard’s paper is reviewed. At first, the idea that these bones represent some form of ancient crocodile is favoured. Embryonic teeth ready to replace already emerged teeth were noticed.

However, to test this theory one of the conical fossil teeth was split open. He mistook evidence for an embryonic tooth ready to replace a broken tooth in the jaw as an accumulation of calcite and hence, Everard wrongly concluded that this creature was not a reptile. The sclerotic ring of bone around the eye reminded the anatomist of the eye of a fish, but when the plates were counted that make up this ring of bone (13), he commented that the fossil may have affinities with the bird family as this number of bones is found only in eyes of birds.

Anatomy Like a Fish

The position of the nostrils and the shape of the lower jaw is considered to be very like those seen in fish. The freshwater Pike is mentioned, although there are other parts of the skeleton that seem to confuse Sir Everard still further. The shoulder blades both in their shape and size are reported as being similar to those found in crocodiles, part of the fossil material is even compared to the bones of a turtle.

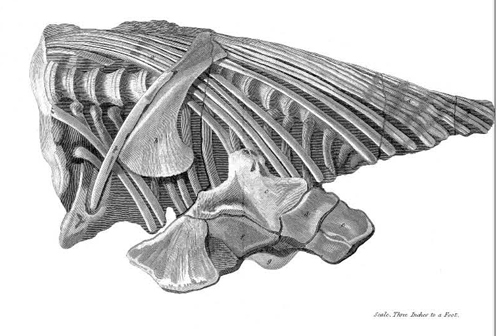

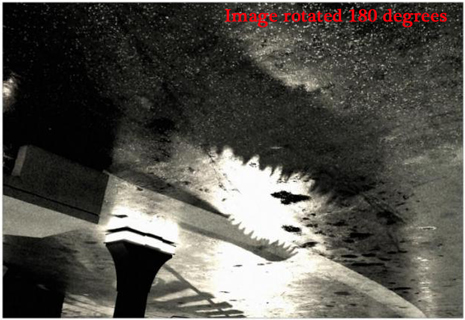

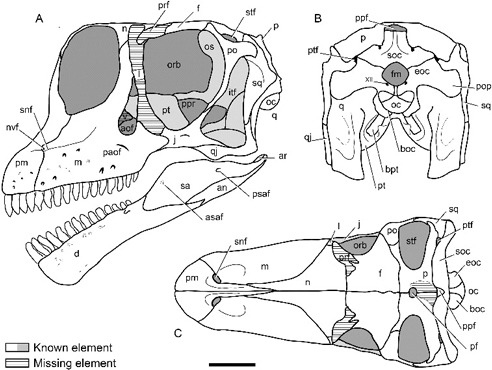

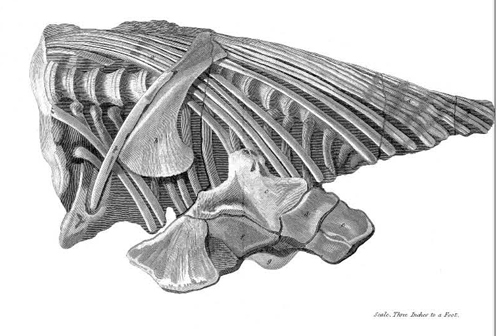

One of the Illustrative Plates from the Original Paper

One of the illustrations by William Clift.

Paper credit: Royal Society (William Clift)

The paper concludes by stating:

“These particulars, in which the bones of this animal differ from those of fishes, are sufficient to show that although the mode of its progressive motion has induced me to place it in that class, I by no means consider it wholly a fish, when compared with other fishes, but rather view it in a similar light to those animals met with in New South Wales, which appear to be so many deviations from ordinary structure, for the purpose of making intermediate connecting links, to unite in the closest manner the classes of which the great chain of animated beings is composed.”

Our baffled author had described a few years early the Duck-billed Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) after specimens were brought back from eastern Australia. Sir Everard is referring to the Platypus when he writes of “those animals met with in New South Wales”.

A Pilloried Paper

Much of the French scientific establishment (and a significant number of British scientists) pilloried this paper. The difference being, the French who were at war could do it openly, however, in Britain, such was the power and influence of Sir Everard Home, no one dared challenge his assumptions openly.

It was perhaps because of Sir Everard’s influence and strong standing within the Royal Society, that the Reverend William Buckland along with the Reverend Coneybeare supported by up and coming geologists such as Henry de la Beche published a rival scientific paper on the Annings’s discovery in the journals of the Geological Society. This paper correctly identified that the fossils were reptilian.

Sir Everard, although ridiculed by other academics continued to work on the puzzling ichthyosaur specimens. Five years after his 1814 paper, he thought he had finally solved the mystery as to this strange creature’s anatomical classification. A new vertebrate to science, referred to as a “Proteus” had been described by a Viennese doctor some years earlier. This was a blind, amphibian of the salamander family (Proteus anguinus) that lived in freshwater streams and lakes deep in caves. Sir Everard mistakenly concluded that the Lyme Regis fossils were a link between the strange Proteus and modern lizards. From then on he referred to the 1814 specimen as a “Proteosaurus”. However, this name never was accepted by scientific circles as the moniker Ichthyosaurus (Fish Lizard) had been erected a year earlier by Charles Konig of the British Museum where the Ichthyosaur specimen resided.

Ironically, as our knowledge of the ichthyosaur Order has grown over the years, so the Lyme Regis specimen has been renamed. It is no longer regarded as an Ichthyosaurus, as the fossils indicate a creature more than five metres in length, much larger than those animals that make up the Ichthyosaurus genus today. In the late 1880s it was renamed Temnodontosaurus (cutting tooth lizard). The Lyme Regis specimen, studied all those years earlier by Sir Everard Home, was named the type specimen with the species name Temnodontosaurus platyodon.

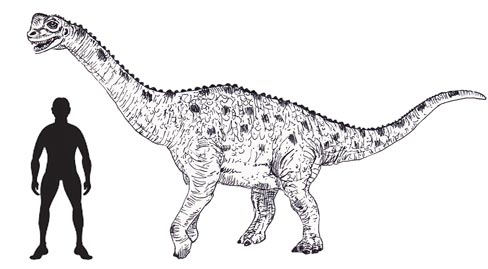

A Close up of the Head of a Typical Ichthyosaur

An Ichthyosaurus with an ammonite that it has caught.

Picture credit: Safari Ltd

For models and replicas of marine reptiles and other prehistoric creatures: Wild Safari Prehistoric World Models.

The 1814 paper might say more about the petty rivalries and snobbery that dogged British scientific circles than it adds to our knowledge of the Ichthyosauria. However, there is one final point to be made. Accompanying the notes were brilliant illustrations of the fossil material, carefully and skilfully prepared by the naturalist William Clift.

The child of a poor family from Devon, William had shown a talent for art from a young age. His illustrative skills were noticed by one of the local gentry, a Colonel whose wife happened to know Anne Home, the sister of Everard who had married John Hunter. When John Hunter was looking for an apprentice to help classify and catalogue his growing collection of specimens at the Royal College of Surgeons, Clift was recommended. He quickly rose to prominence and despite being hampered by the removal of many of John Hunter’s manuscripts by Everard, Clift’s reputation grew and grew. His daughter, Caroline Ameila Clift married Professor Richard Owen (later Sir Richard Owen), the anatomist who is credited with the naming of the Dinosauria and the establishment of the Natural History Museum in London.