Largest Silurian Vertebrate Discovered to Date

Megamastax – Silurian Equivalent of “Jaws”

A team of scientists from Flinders University (Adelaide, South Australia) and the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology (Beijing), have announced the discovery of a new genus of primitive fish from the Silurian-aged deposits of Yunnan Province (south-western, China). There have been a number of ancient fish species described from Chinese excavations in recent years, but there has been nothing like this fish ever found before, for a start it is at least three times as big as any other Silurian vertebrate and it had a mouth and teeth designed for eating other marine creatures. This was the Silurian equivalent of Tyrannosaurus rex, an apex predator that swam in a warm, tropical sea some 423 million years ago.

The prehistoric predator has been named Megamastax amblyodus, the name means “big mouth with blunt teeth”, one of the lead researchers and authors of the scientific paper on this new carnivore, Dr Brian Choo, describes Megamastax as a member of the sarcopterygians or lobe-finned fish, the group of jawed vertebrates that are believed to have given rise to the tetrapods (four-legged, land animals and our own ancestors).

Scientists now think that the sarcopterygians evolved in the Late Silurian and rapidly diversified, out competing the jawless fish (the agnathans). Fossils found in Yunnan Province in the late 1990s proved that the sarcopterygians did indeed have Silurian origins and they did not evolve in the later Devonian as previously thought, however, the discovery of a relative giant throws up some intriguing questions. For example, did the sarcopterygians evolve earlier, or did they diversify extremely rapidly giving rise to a myriad of new forms including apex predators.

An Artist’s Illustration of Megamastax amblyodus

Picture credit: Dr Brian Choo

Three specimens have been found so far, the largest had a jaw seventeen centimetres long and a total body length of around one metre. In the picture above, M. amblyodus is pictured attacking and feeding on a shoal of agnathans (Dunyu longiforus). This discovery challenges the assumption that large vertebrates did not evolve until the Devonian, Dr Choo commented:

“It’s always been thought that Silurian fish were all small because, until now, no fossils of species more than 30 cm or so in length have ever been discovered. But from the site in Yunnan, near the city of Qujing, we uncovered a diverse collection of jawed fish from Silurian sediments, including the new Megamastax, a predator vastly larger than any other vertebrate known from this age.”

Not only does this new fossil discovery change views on marine ecosystems, but it adds a twist to the current debate about the palaeoclimate of Earth. With only small vertebrates found, scientists thought that there was not enough atmospheric oxygen to permit the evolution of large back-boned animals.

Dr Choo, a post-graduate research fellow at Flinders University explains:

“As modern large fish tend to be more sensitive to oxygen availability than smaller ones, the apparent absence of big Silurian fishes has been used to calibrate some models of Earth’s atmospheric history, with supposedly lower oxygen levels restricting body size prior to the Devonian. However, evidence of a one- metre-long fish swimming about 423 million years ago strongly refutes the idea.”

Megamastax would have competed with larger genera of eurypterids (sea-scorpions) for food resources, some palaeontologists have argued that it was the evolution of large, jawed fishes that led to the demise of many forms of marine arthropod, including the sea-scorpions and many types of trilobite. The rocks that make up the Silurian deposits of Yunnan Province were formed in a shallow sea that made up part of the colossal Panthallassic Ocean that covered virtually all of the Eastern Hemisphere. Yunnan Province lay at the bottom of this shallow sea some more than a thousand miles west of its current location.

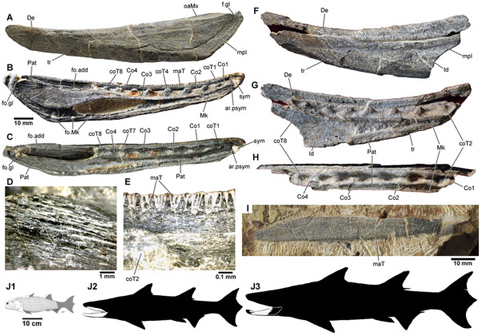

Holotype Fossil Material, Jaws and Teeth in Close Up

Picture credit: Dr Choo et al

The picture above shows pictures of the holotype jaw (IVPP V18499.1) in various views (A) lateral view, outside of jaw, (B) lingual (inside of the mouth view), (C) dorsal view, from the top and (D) close up of marginal teeth. Picture (E) shows a close up of the dentition if viewed from the inside of the mouth – lingual view. Figures F to H show views of the second partial jaw recovered (F = lateral, G = lingual, H = dorsal). Picture I shows the third jaw fragment (V18499.3) viewed from the side (lateral view).

The drawings labelled J1 represents a genus of Silurian fish found in the same layer of strata as M. amblyodus, Guiyu oneiros, G. oneiros may have been the prey. Drawings J2 and J3 represent suggested silhouettes for this new Silurian predator, the smaller sized specimen (J2) is based on smaller jaw fossils, whilst J3 is based on the largest jaw fragment found.

Key to Diagram

Co 1–4, coronoids 1–4; coT 1–8, coronoid teeth 1–8; De, dentary; fo.add, adductor fossa; fo.gl, glenoid fossa; fo.Mk, Meckelian foramen; Id, infradentary; mpl, mandibular pit line; maT, marginal teeth; oaMx, overlap area for maxilla and quadratojugal; Pat, prearticular; sym, area for parasymphysial plate; tr, indented track bordering splenial.

Dr Choo added:

“While by themselves, these fossils do not give an exact indication of what the atmosphere was like in the Silurian, they are still a significant new piece of the puzzle that will be incorporated into further research. These new fossils from Yunnan represent one of the earliest well-documented vertebrate faunas and demonstrate that fish from the latter part of the Silurian were already big and varied, clearly the result of an extended span of evolution. Unfortunately, the only fossils of jawed fish from much older sediments are a few tantalising fragments. There is a much deeper history about which we currently know very little.”