Baby Tyrannosaurs Born Ready to Hunt

A new scientific paper published this week suggests that tyrannosaurs were able to hunt and to look after themselves soon after they hatched. In addition, tyrannosaur hatchlings were surprisingly large, perhaps more than a metre long when they broke out of their eggs and if this the case, then tyrannosaur eggs would have been colossal, perhaps larger than any other dinosaur egg known to science.

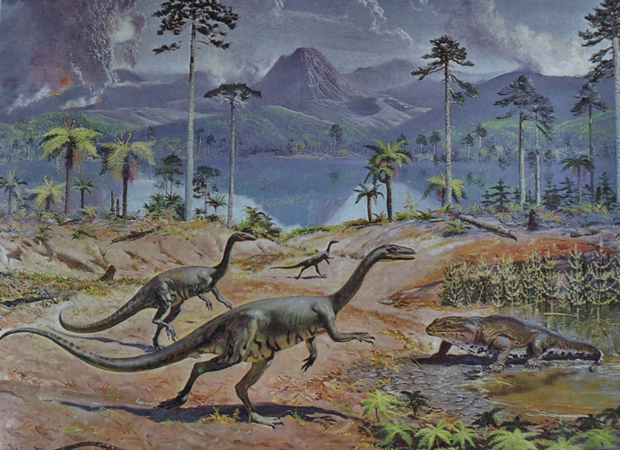

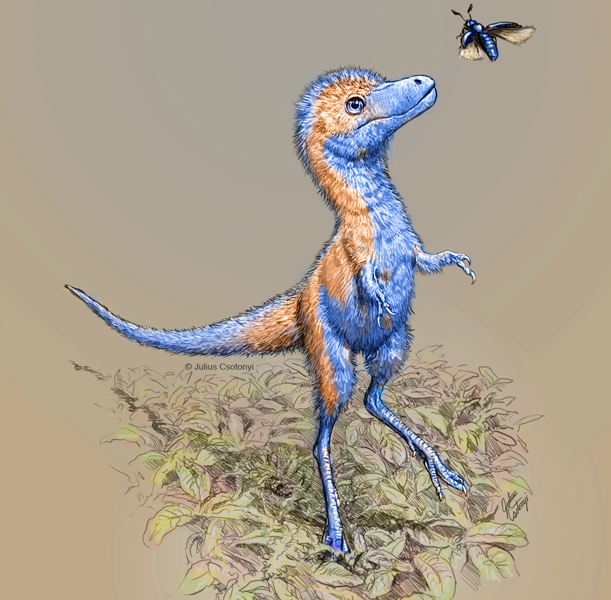

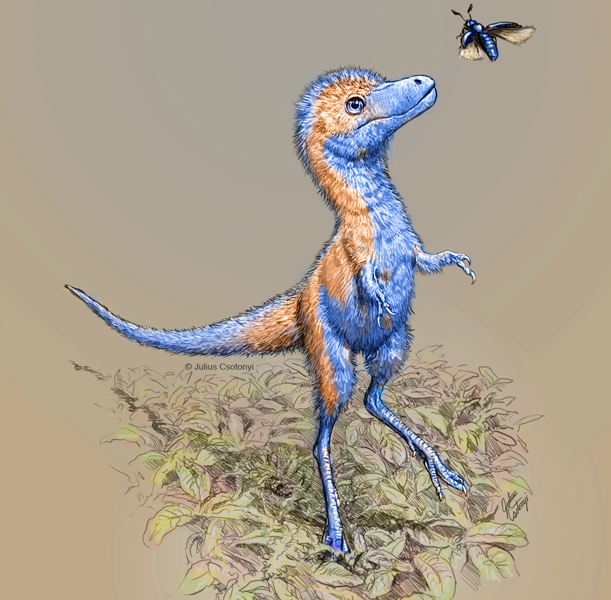

A Life Reconstruction of a Baby Tyrannosaur

A life reconstruction of a juvenile tyrannosaur. This illustration by the talented palaeoartist Julius Csotonyi, depicts a baby tyrannosaur covered in a coat of insulating protofeathers.

Picture credit: Julius Csotonyi

As Big as a Collie Dog

Writing in the latest edition of the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, the scientists which include such eminent figures as Phil Currie, “Jack” Horner and Stephen Brusatte, have written up an on-line presentation from last October which took place at the virtual Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology Conference and they indicate that young tyrannosaurs were big babies. With a length of in excess of 1 metre, that’s about the size of a border collie dog.

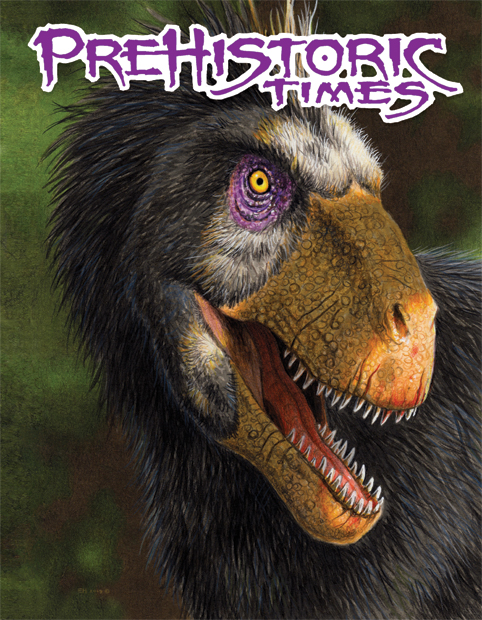

A Model of a Young Tyrannosaurus rex

A young T. rex. Research suggests that Late Cretaceous tyrannosaurs may have been around a metre in length when very young. Rare fossil bones from perinatal tyrannosaurs from North America also suggest that these predators were highly developed and capable of hunting for themselves – precocial development – mobile and relatively fully developed when first hatched.

The model (above) is from the CollectA Prehistoric Life Age of Dinosaurs range.

To view this range: CollectA Prehistoric Life Figures.

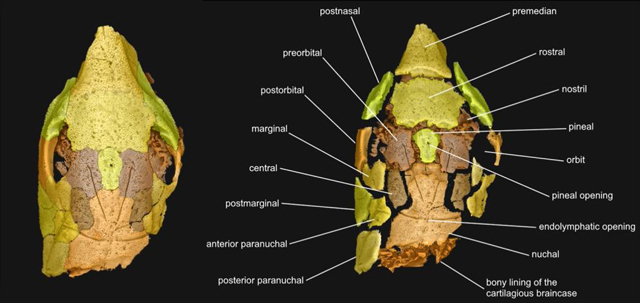

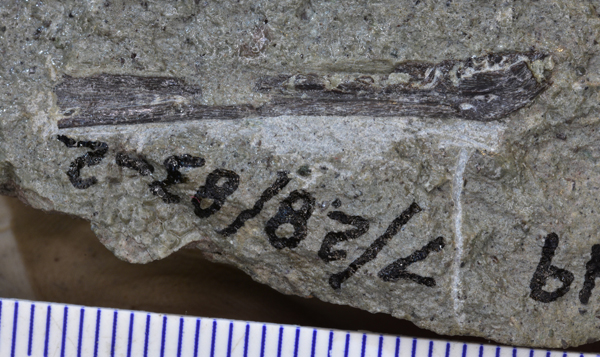

Perinatal Tyrannosaurid Bones and Teeth

Perinatal tyrannosaurid bones and teeth from the Campanian–Maastrichtian of western North America provide the first window into this critical period of the life of a tyrannosaurid. An embryonic dentary (Daspletosaurus horneri) from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana, measuring just 3 cm in length, already exhibits distinctive tyrannosaurine characters like a “chin” and a deep Meckelian groove, and reveals the earliest stages of tooth development. When considered together with a remarkably large embryonic claw bone (ungual) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta and believed to have come from an Albertosaurus sarcophagus, a minimum hatchling size for tyrannosaurids could be estimated by the research team.

Corresponding author for the paper, Gregory Funston (University of Edinburgh), stated:

“It appears that tyrannosaurs were born ready to hunt, already possessing some of the key adaptations that gave tyrannosaurs their powerful bites. So, it’s likely that they were capable of hunting fairly quickly after birth, but we need more fossils to tell exactly how fast that was.”

Tyrannosaur Babies Bigger than Other Dinosaur Babies

The dentary and the claw bone indicate that Late Cretaceous tyrannosaurs were bigger than any other known dinosaur babies. The researchers conclude that they must have hatched from enormous eggs, perhaps exceeding the 43 cm length of largest dinosaur eggs described to date.

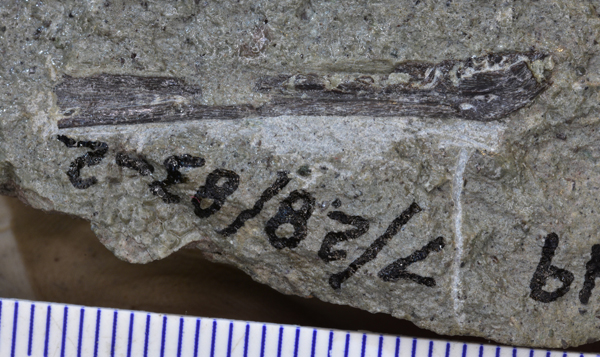

The Embryonic Tyrannosaur Dentary

The fossilised lower jawbone (dentary) of a Daspletosaurus horneri, one of the first baby tyrannosaurs ever discovered.

Picture credit: Gregory F. Funston (University of Edinburgh)

Studying Embryonic Fossil Material

Co-author of the paper, Mark Powers a PhD student at the University of Alberta (Canada), commented:

“Tyrannosaurs are represented by dozens of skeletons and thousands of isolated bones or partial skeletons, but despite this wealth of data for tyrannosaur biology, the smallest identifiable individuals are aged three to four years old, much larger than when they would have hatched. No tyrannosaur eggs or embryos have been found even after 150 years of searching—until now.”

The study, focused on the two fossils representing perinatal development of tyrannosaurids. The ungual was found near Morrin in the province of Alberta, whilst the dentary came from Montana. The ungual is approximately 71.5 million years old, and the jawbone a little older at around 75 million years old.

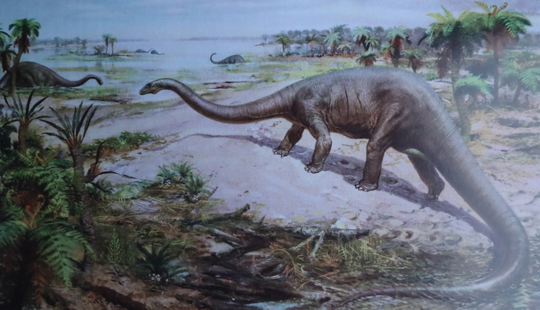

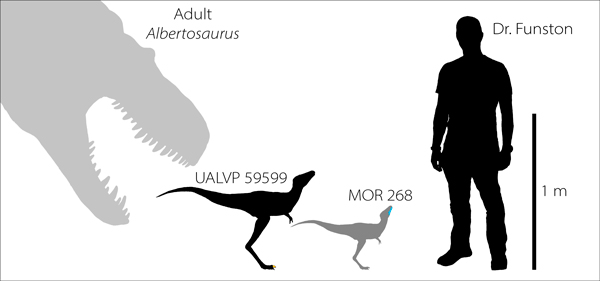

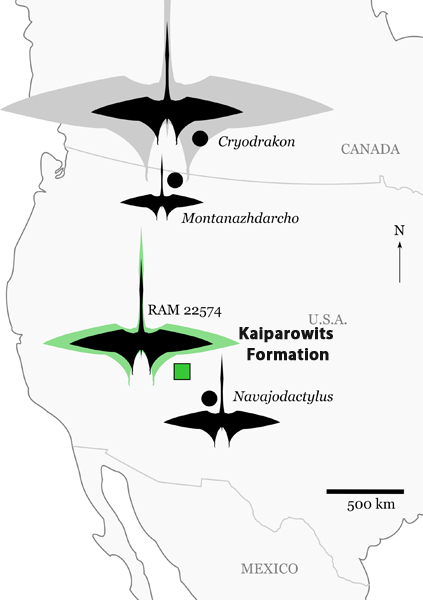

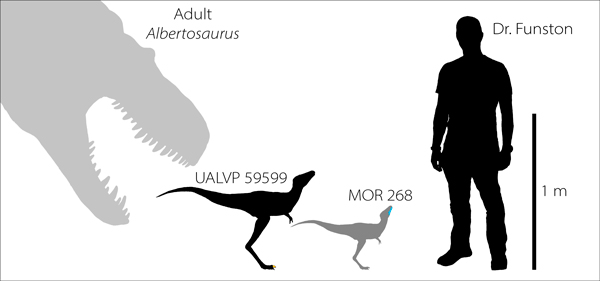

Comparing the Tyrannosaurid Fossil Material with Dr Funston and an Adult Albertosaurus

This diagram compares the size of a full-grown Albertosaurus with that of palaeontologist Greg Funston and the two dinosaur embryos whose toe claw and jawbone were identified in a newly published study.

Picture credit: Gregory F. Funston (University of Edinburgh)

Mark Powers, who completed the research as a master’s student supervised by Phil Currie added:

“The discovery of embryonic material is a huge find in our efforts to understand how some of the most popular and charismatic dinosaurs began their life and grew to immense sizes. It provides a much-needed—and until now, missing—data point depicting the starting point for tyrannosaur growth.”

Surprising Results

The researchers were surprised to find that the small tyrannosaur teeth in the lower jaw were distinct from the teeth of older tyrannosaurids. They had not developed true serrations running along the cutting edges. In addition, the toe claw (specimen number UALVP 59599), came from an animal estimated to be about 1.1 metres long, whilst the tiny jawbone (MOR 268), came from a tyrannosaur around 71 cm in length.

The size estimates for perinatal tyrannosaurs based on this study reinforce the work of the late American-Canadian palaeontologist Dale Russell, who back in 1970 provided some of the first insights into tyrannosaur development and ontogeny. This study was published in a special issue of the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences which honours the contribution made to vertebrate palaeontology by Professor Russell.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Alberta in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Baby tyrannosaurid bones and teeth from the Late Cretaceous of western North America” by Gregory F. Funston, Mark J. Powers, S. Amber Whitebone, Stephen L. Brusatte, John B. Scannella, John R. Horner and Philip J. Currie published in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.

Visit the award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.