New Research Revises the Way Dinosaurs Look

For Dinosaurs Think “Fuzzysaurs”

A new study suggests that dinosaurs may have been somewhat more fluffy than previously thought. To date, most illustrations of feathered dinosaurs have been analogous to modern, living birds, after all, the majority of scientists believe that birds are living dinosaurs and closely related to a group of theropod dinosaurs (Maniraptora). However, in a paper published in the journal of the Palaeontological Association, a team of Bristol University researchers have revealed new details about feathered dinosaurs, allowing palaeoartists the chance to refine how these animals are depicted.

It seems that dinosaurs may have been quite fluffy, a feathered theropod dinosaur is one thing, but a fuzzy Velociraptor, that may take a little while to sink in.

New Study Gives Anchiornis a New Look

Picture credit: Rebecca Gelernter

The Contour Feathers of Anchiornis

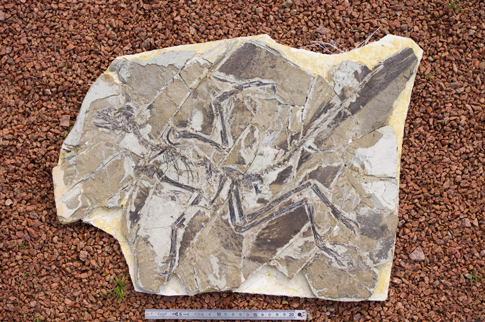

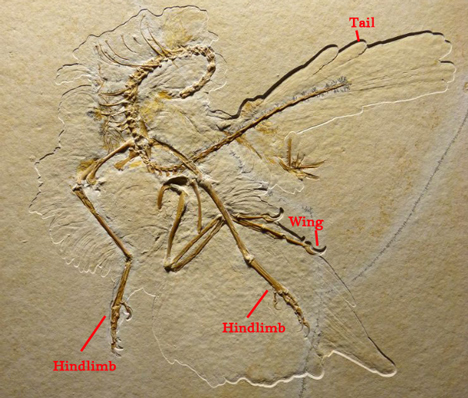

The researchers, which included Dr Jakob Vinther (Bristol University), examined, at high resolution, an exceptionally well-preserved fossil of an Anchiornis (A. huxleyi) comparing its fossilised feathers to those of other dinosaurs and extinct birds. Anchiornis is known from numerous fossil specimens from north-eastern China (Liaoning Province). It is likely that the specimens hail from the Tiaojishan Formation of Upper Jurassic rocks and these fossils are estimated to be around 160 million years old. Where this crow-sized, four-winged creature sits (or should that be perches/or clambers), on the Dinosauria family tree remains open to debate.

The fossils may precede Archaeopteryx by several million years and when first described Anchiornis (the name means “near bird”), was seen as a transitional form, very close to the split between dinosaurs and birds (Aves). Other studies have challenged this placement, with an affinity with the troodontids being proposed.

Currently, the consensus seems to be that Anchiornis is a basal member of the Paraves clade, a part of the Maniraptora that incorporates the dromaeosaurids, the troodontids and the avialans, those dinosaurs that lead directly to birds as we know them today.

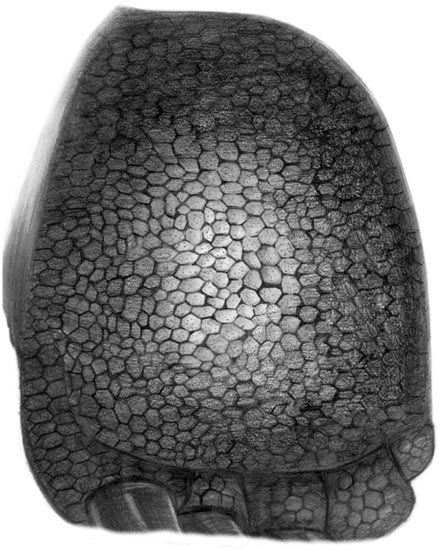

Anchiornis huxleyi – The PNSO Figure

To view the range of prehistoric animals made by PNSO: PNSO Age of Dinosaurs Models.

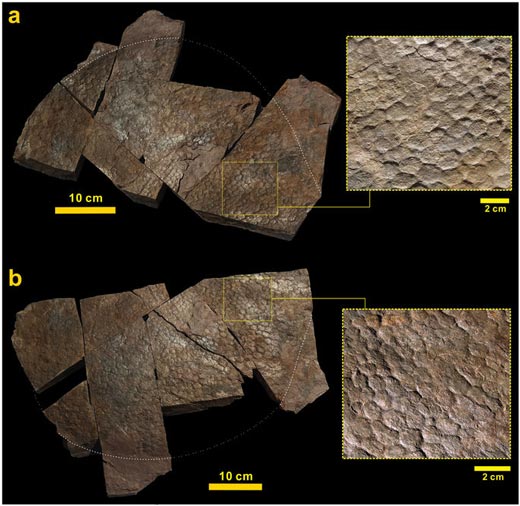

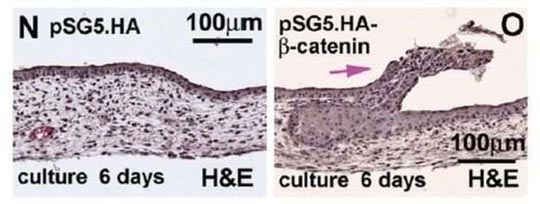

The feathers around the body of Anchiornis, known as contour feathers, revealed a newly-described, extinct, primitive feather form consisting of a short quill with long, independent, flexible barbs erupting from the quill at low angles to form two vanes and a forked feather shape. The scientists conclude that the details of the contour fossils were preserved as some of these feathers became detached from the body during decomposition. When buried and fossilised, this taphonomy made the feather structure easier to analyse.

Fluffy Anchiornis

Such feathers would have given Anchiornis a fluffy appearance relative to the streamlined bodies of modern flying birds, whose feathers have tightly-zipped vanes forming continuous surfaces. Anchiornis’s unzipped feathers might have affected the animal’s ability to control its temperature and repel water, possibly being less effective than the vanes of most modern feathers. This shaggy, fuzzy plumage would also have increased drag when Anchiornis took to the air. It was probably not capable of powered flight, most likely it was a glider, however, these contour feathers lacked the aerodynamic qualities of the feathers of extant birds.

Comparing Contour Feathers – Anchiornis Against a More Recent Fossil Specimen

Picture credit: Bristol University

Having to Compensate for the Forked Contour Feathers

In addition, the wing feathers of Anchiornis lack the aerodynamic, asymmetrical qualities of modern flight feathers. This new study shows that the vanes on the feathers of Anchiornis were not so tightly “zipped” together when compared to those of modern birds. The feathers of Anchiornis would have provided little lift for the animal, so to compensate paravians like Anchiornis packed many rows of long feathers into the wing, in contrast to extant, volant birds where most of the wing surface is formed by just one row of feathers.

Anchiornis had four wings, feathers on the legs as well as the arms and elongated feathers on the tail. These structures would have increased the surface area of the animal assisting with gliding and helping to keep the animal stable in mid-air.

Palaeoartist Works with Palaeontologists

Scientific illustrator Rebecca Gelernter collaborated with researchers Evan Saitta and Dr Vinther, (University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences and School of Biological Sciences), to produce a life reconstruction of Anchiornis (see above). The colour patterns in Rebecca’s illustration are very similar to those in the earlier drawing produced by Julius Csotonyi, details of the feather pigmentation of Anchiornis had been revealed in a previous study, but this new illustration shows a more fuzzy, fluffy prehistoric animal.

Commenting on the new depiction of Anchiornis, researcher Evan Saitta said:

“The novel aspects of the wing and contour feathers, as well as fully-feathered hands and feet, are added to the depiction. Most provocatively, Anchiornis is presented in this artwork climbing in the manner of Hoatzin chicks, the only living bird whose juveniles retain a relic of their dinosaurian past, a functional claw. This contrasts much previous art that places paravians perched on top of branches like modern birds. However, such perching is unlikely given the lack of a reversed toe as in modern perching birds and climbing is consistent with the well-developed arms and claws in paravians. Overall, our study provides some new insight into the appearance of dinosaurs, their behaviour and physiology, and the evolution of feathers, birds, and powered flight.”

Anchiornis Fossil Material (Liaoning Province)

Picture credit: Thierry Hubin

Rebecca Gelernter added:

“Paleoart is a weird blend of strict anatomical drawing, wildlife art, and speculative biology. The goal is to depict extinct animals and plants as accurately as possible given the available data and knowledge of the subject’s closest living relatives. As a result of this study and other recent work, this is now possible to an unprecedented degree for Anchiornis. It’s easy to see it as a living animal with complex behaviours, not just a flattened fossil.”

For an article published in March 2017 that provides further information on Anchiornis research: Very Near to “Near Bird”.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a Bristol University press release in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Additional Information on the Primitive Contour and Wing Feathering of Paravian Dinosaurs” by E. Saitta, R. Gelernter and J. Vinther published in Palaeontology, the journal of the Palaeontological Association.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.