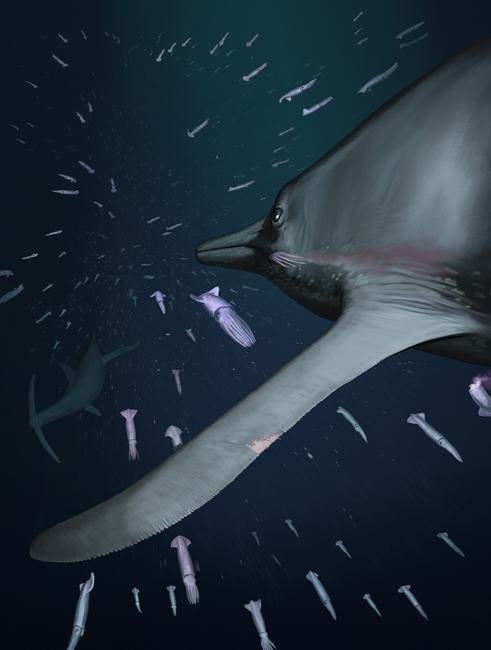

A remarkable fossilised ichthyosaur flipper has provided new insights into the hunting behaviour of ancient marine reptiles. The study, published in the journal “Nature” reveals that the giant ichthyosaur Temnodontosaurus trigonodon relied on stealth whilst hunting in the darkness. The metre-long front flipper was equipped with flow control structures that probably served to suppress self-generated noise as this megapredator hunted in dimly lit pelagic environments.

Life reconstruction of the giant Jurassic ichthyosaur Temnodontosaurus trigonodon hunting in the depths. The artwork highlights the winglike flipper, and the unusual structures observed in the fin. Picture credit: Joschua Knüppe.

Picture credit: Joschua Knüppe

Temnodontosaurus trigonodon Flipper Study

Temnodontosaurus was a large ichthyosaur. Size estimates vary, however, some individuals may have exceeded ten metres in length. Researchers have named several species within the genus. While fragmentary remains of unusual “fish lizards” had previously been excavated along the Dorset coast, it was the discovery of a metre-long skull by Joseph Anning at Lyme Regis in the autumn of 1811—followed by vertebrae and ribs found by 13-year-old Mary Anning in 1812 that prompted the first formal scientific study and description of an ichthyosaur. More than two centuries later, these enigmatic marine reptiles continue to yield unexpected insights and discoveries.

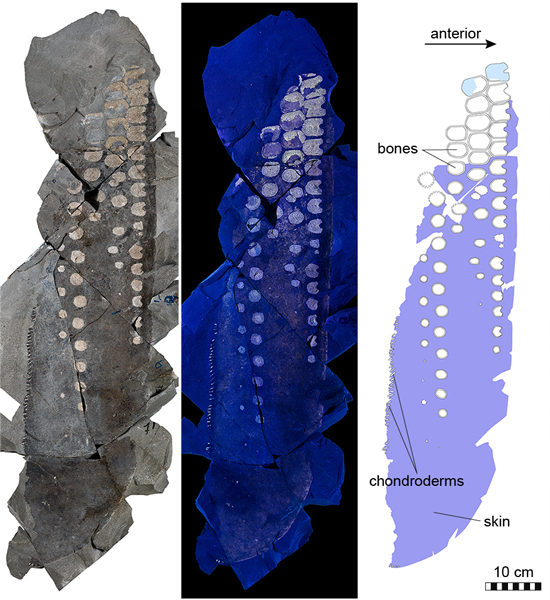

The fossilised flipper (specimen number SSN8DOR11) was collected from a temporary exposure of dark, laminated limestone (Lower Toarcian Posidonia Shale) of southwestern Germany. The partial front flipper preserves soft tissue structures and has been studied by an international team of researchers led by Dr Johan Lindgren from Lund University in Sweden. The research was undertaken in collaboration with Dr Dean Lomax, an 1851 Research Fellow at the University of Bristol, who has been working on the fossil for about six years. Dr Lomax is one of the world’s leading ichthyosaur experts.

Dr Dean Lomax and Dr Johan Lindgren, together with fellow researcher Sven Sachs, examining one part of the Temnodontosaurus trigonodon flipper at Lund University, Sweden. Picture credit: Katrin Sachs.

Picture credit: Katrin Sachs

Dr Lindgren, who has pioneered research into marine reptile soft tissues commented:

“The wing-like shape of the flipper, together with the lack of bones in the distal end and distinctly serrated trailing edge collectively indicate that this massive animal had evolved means to minimise sound production during swimming. Accordingly, this ichthyosaur must have moved almost silently through the water, in a manner similar to how living owls—whose wing feathers also form a zigzag pattern—fly quietly when hunting at night. We have never seen such elaborate evolutionary adaptations in a marine animal before.”

The remarkable fossil flipper specimen (SSN8DOR11) shown left, under UV light (centre) and in a line drawing (right). Picture credit: Randolph G. De La Garza, Martin Jarenmark and Johan Lindgren.

Picture credit: Randolph G. De La Garza, Martin Jarenmark and Johan Lindgren

“Silent Swimming”

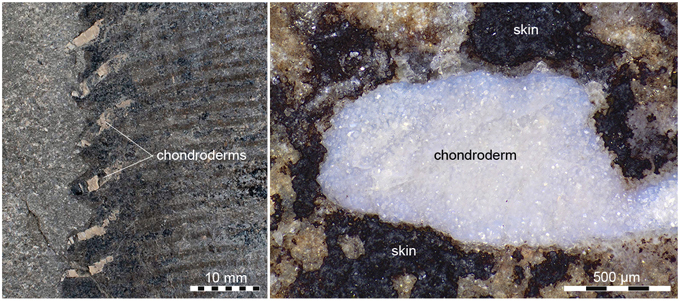

Although there are many exceptional ichthyosaur specimens with soft-tissue preservation, most soft tissues are associated with the fossilised remains of much smaller dolphin-sized species. This is a remarkable discovery, it represents the first-ever soft tissues associated with a large-bodied ichthyosaur. In addition, the research team have identified unique structures never observed before in an aquatic animal. The crenulated trailing edge of the wing-shaped flipper being reinforced by novel, mineralised, rod-like structures. The researchers have named these structures “chondroderms”.

Dr Dean Lomax, who is also a palaeontologist at the University of Manchester, said:

“The first time I saw the specimen, I knew it was unique. Having examined thousands of ichthyosaurs, I had never seen anything quite like it. This discovery will revolutionise the way we look at and reconstruct ichthyosaurs (and possibly also other ancient marine reptiles) but specifically soft-tissue structures in prehistoric animals.”

Novel cartilaginous integumentary structures. To the left, light micrograph of the crenulated trailing edge in SSN8DOR11. Note that each serration is supported by a centrally located chondroderm. To the right, magnified image of a distal chondroderm. Picture credit: Randolph G. De La Garza, Martin Jarenmark and Johan Lindgren.

Picture credit: Randolph G. De La Garza, Martin Jarenmark and Johan Lindgren

The team postulate that this huge predator relied on underwater stealth, or “silent swimming” while hunting in the depths, in much the same way that owls as nocturnal predators have almost silent flight.

Eyes as Big as Footballs

Temnodontosaurus had the largest eyes of any vertebrate known. The eye sockets of some specimens are more than twenty-five centimetres in diameter. These huge eyes lend further support to the theory that Temnodontosaurus hunted under low-light conditions, either at night or in deep waters.

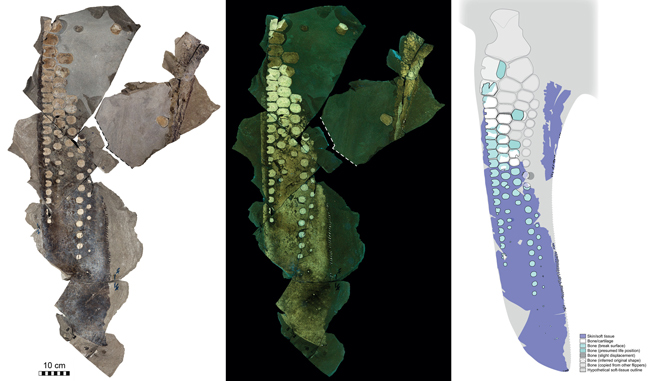

Spectacular, 183-million-year-old soft-tissue fossil (SSN8DOR11; Paläontologisches Museum Nierstein, Nierstein, Germany): an isolated wing-like front flipper of the giant predatory ichthyosaur Temnodontosaurus (T. trigonodon). Photograph (left) and shown under UV light (centre). Line drawing (right) providing a representation of the metre-long flipper. Picture credit: Randolph G. De La Garza, Martin Jarenmark and Johan Lindgren.

Picture credit: Randolph G. De La Garza, Martin Jarenmark and Johan Lindgren

The remarkable fossilised flipper was discovered by fossil collector Georg Göltz, a co-author on the new study. Amazingly, Georg made the find entirely by chance whilst looking for fossils at a temporary exposure at a road cutting in the municipality of Dotternhausen, Germany. The fossil consists of both the part and counterpart (opposing sides) of almost an entire front flipper. Georg continued to look for more remains, but no other fossil material was found.

As the proximal part of the fin is absent, it has been speculated that the flipper could have been ripped off by an even larger ichthyosaur. The specimen was shown to palaeontologist and study co-author Sven Sachs (Natural History Museum, Bielefeld). Dr Sachs immediately recognised the rarity of the find.

A multidisciplinary research team employed a variety of sensitive imaging, elemental and molecular analyses to examine the unique preserved structures. This involved high-end techniques such as synchrotron radiation-based X-ray microtomography at the Swiss Light Source SLS at PSI and Diamond Light Source, time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry and infrared microspectroscopy, along with the reconstruction of a virtual model using computational fluid dynamics.

To recreate the stealth hunting behaviours of a marine reptile that lived more than 180 million years ago is remarkable. Furthermore, by studying the fin morphology, scientists could find ways of reducing our impact on modern marine soundscapes.

Going Back to Mary Anning

For Dr Dean Lomax, this astonishing study harks all the way to back to the days of pioneering palaeontologist Mary Anning and her older brother Joseph.

He stated:

“In a weird way, I feel that there is a wonderful full-circle moment that goes back to Mary Anning showcasing that even after two hundred years, we are still uncovering exciting and surprising finds that link back to her initial discoveries.”

Dr Lomax added:

“The fossil provides new information on the flipper soft tissues of this enormous leviathan. It has structures never seen in any animal, and reveals a unique hunting strategy thus providing evidence of its behaviour, all combined with the fact that its noise-reducing features may even help us to reduce human-made noise pollution. Although I might be a little bias, in my opinion, this represents one of the greatest fossil discoveries ever made.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bristol in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Adaptations for stealth in the wing-like flippers of a large ichthyosaur” by Johan Lindgren, Dean R. Lomax, Robert-Zoltán Szász, Miguel Marx, Johan Revstedt, Georg Göltz, Sven Sachs, Randolph G. De La Garza, Miriam Heingård, Martin Jarenmark, Kristina Ydström, Peter Sjövall, Frank Osbæck, Stephen A. Hall, Michiel Op de Beeck, Mats E. Eriksson, Carl Alwmark, Federica Marone, Alexander Liptak, Robert Atwood, Genoveva Burca, Per Uvdal, Per Persson and Dan-Eric Nilsson published in the journal Nature.

Visit the website of the award-winning palaeontologist and author Dr Dean Lomax: Palaeontologist Dr Dean Lomax.

Leave A Comment