Anthracosuchus balrogus Giant Palaeocene Crocodile Named in New Research

Columbian Giant Crocodile – Anthracosuchus balrogus

Vertebrate fossils from a coal mine in north-eastern Columbia have provided palaeontologists with a fascinating insight into life in the tropics in the first few million years after the Cretaceous mass extinction event. The dinosaurs may have gone but preserved in the Cerrejón Formation are the remains of giant reptiles who were the apex predators within this rainforest community. A paper has just been published in the scientific journal “Historical Biology” that reports on the discovery of yet another large crocodile genus from this locality, one that probably preyed upon giant turtles, it in turn may have been hunted by Titanoboa, the largest snake known to science.

“Living Fossils”

Crocodiles may be referred to as “living fossils”, a term that most palaeontologists dislike as it suggests that organisms do not change much over time. True, the basic body plan (bauplan) of the crocodilians may not have changed much since the early Mesozoic, but the fossil record shows that crocodiles evolved to occupy a vast array of ecological niches. This new discovery, a crocodile named Anthracosuchus demonstrates this as it had a blunt, short snout, in direct contrast to its long-snouted close relatives.

The new species lived in what was an inland, freshwater environment, an extensive tropical floodplain that was covered in dense jungle and crossed by a number of large rivers which led into the nascent Caribbean Sea. South America was an island, there was also a substantial marine intrusion to the west of the Cerrejón Formation, this marine environment stretching into what is now central Bolivia. Reptiles dominated the ecosystem and at 4.8 metres in length Anthracosuchus, with its very powerful jaws was probably a top predator.

Views of Skull Material Ascribed to this Genus (A. balrogus)

Picture credit: Alexander K. Hastings et al

Anthracosuchus balrogus

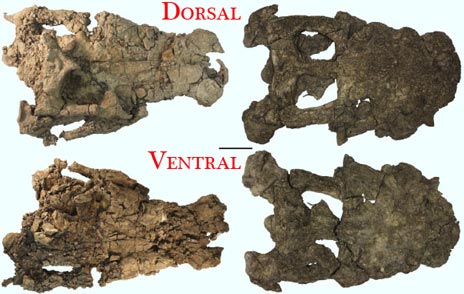

The picture above shows two of the four fossil skulls assigned to this new genus. The top images are a view of the skulls looking down onto them, viewing the top (dorsal view), the two images underneath are views of the underside of the skulls (ventral view). All the fossil material including limb bones, teeth and osteoderms (armoured scales) were excavated from a clay layer immediately below a layer of coal in the Cerrejón mine.

The fossils date from 58-60 million years ago (Palaeocene). This crocodile has been classed as a member of the dyrosaurid crocodiles, a widely dispersed group of Late Cretaceous/Palaeocene crocodiles that, for the most part are marine and characterised by long, narrow snouts. Here is a member of the Dyrosauridae, with a very different snout and one from strata laid down inland. These types of crocodile are now extinct, it is believed an ancestor of the dyrosaurids was the mighty Sarcosuchus whose fossils are associated with Cretaceous aged strata from Niger (Africa).

Discovered in 2005

The first skull of this new dyrosaurid was discovered in 2005, but the skull was missing its front end. The back of the skull indicated that this type of crocodile probably had a blunt, short snout. This was confirmed in 2007 when a second skull, this time with its front end intact, was found. Two more skulls were excavated later on that year, making the total number of individuals known to be at least four.

The new species of crocodile was discovered by a team of University of Florida researchers, led by Jonathan Bloch, Associate Curator of Vertebrate Palaeontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, Alexander Hastings (Florida Museum of Natural History), assisted by Carlos Jaramillo, a palaeobotanist with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. All specimens of the new taxon are deposited at the Museo Geológico José Royo y Gómez, Colombian Geological Survey, Bogotá, Colombia. Casts of these specimens are also deposited at the collections of the Florida Museum of Natural History.

“Coal Crocodile”

Anthracosuchus means “coal crocodile”, a reference to the fossil remains being found adjacent to a coal seam. The trivial or specific name is derived from “Balrog”, a fiery demon that features in Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings”. Balrog inhabited the deep mines of Moria, so since this crocodile’s fossils have been found in a mine, the trivial name is very apt.

A number of crocodile fossils have been found at the Cerrejón site, to read about the discovery of another, related crocodile species: New Crocodile Species in Columbian Mine.

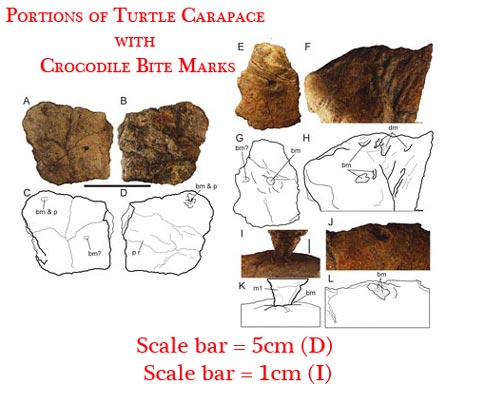

Remains of turtle shells, discovered in close proximity to the crocodile fossils, show signs of damage. There are scratches, most likely made by teeth and also at least one example of a healed bite mark. The scratches and bite marks match the profile of the teeth of A. balrogus, this suggests that this crocodile, related to long-snouted dyrosaurids, adapted to an inland habitat and a diet of turtles.

Fossilised Turtle Carapace Showing Traces of Crocodile Bites

Picture Credit: Alexander K. Hastings et al

The picture above shows a fragment of shell (A) and a line drawing (C) viewed from above (dorsal view). Picture B and the line drawing D, are the same fragment but this time, viewed from below (ventral view). Potential bite marks (bm) and bone regrowth after a bite (bm&p) are illustrated.

Damage to a Turtle Shell

Picture E and line drawing G are of a fragment of turtle shell viewed from the top that shows further damage, once again bite marks (bm) are indicated. Picture F and its associated line drawing H show another fragment, bite marks and drag marks (dm) are illustrated. Picture I and drawing J show a tooth from Anthracosuchus balrogus is analogous to the damage seen on the turtle shell fragments. Image J and L shows a turtle fragment viewed from the top (dorsal) with bite marks.

Coeval with Titanoboa

This crocodile certainly had a very powerful bite, however, it shared its environment with the largest snake known to science, the immense Titanoboa (T. cerrejonensis). At more than three times the size of Anthracosaurus this constrictor may have preyed upon adult crocodiles. Anthracosaurus in turn, may have hunted and eaten immature Titanoboas. Battles between these large reptiles would have been a spectacular sight.

Titanoboa Tackles a Large Anthracosuchus

Picture credit: Florida Natural History Museum

To read about the discovery of Titanoboa: Titanoboa – Giant Prehistoric Snake of the Palaeocene.

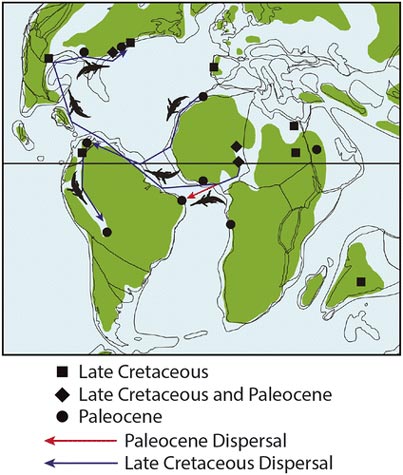

The Dyrosauridae are one of the very few types of large, marine reptile that survived the Cretaceous mass extinction event. The discovery of a broad-snouted genus in South America will help scientists to identify how these creatures adapted to new environments. It will also help them to piece together how these crocodiles dispersed across much of the globe from their African origins. Fossil evidence suggests that during the Cretaceous, when the Atlantic ocean was not as wide as it is today, there were a number of dispersals of marine dyrosaurid crocodiles from Africa to the Americas. This trend seems to have continued into the early Cenozoic, with migrations east to west during the Palaeocene epoch.

Researchers Map the Dispersal of Dryosaurid Crocodiles from Africa

Picture credit: Alexander K. Hastings et al