Spinosaurids are like buses, you wait for ages for one to come along and then two arrive together. Today, we can announce that two new members of the Baryonychinae have been named and described from fossil remains found on the Isle of Wight. Named Ceratosuchops inferodios and Riparovenator milnerae, their discovery supports the idea of a European origin for the Spinosauridae and suggests that different types of fish-eating dinosaur could happily co-exist in the same palaeoenvironments.

Spinosaurs Had Been Expected

Palaeontologists had long suspected that there were more spinosaurid dinosaurs awaiting discovery in the Lower Cretaceous Wealden Supergroup of southern England. The strata were deposited over large flood plains during the late Barremian and early Aptian stages of the Early Cretaceous and fragmentary fossils, mostly isolated teeth representing spinosaurids have been found. These fossils were usually ascribed to Baryonyx, which was formally named and described in 1986 and provided scientists with the first significant evidence of the body plan and diet of these specialised theropods.

New Spinosaurids Fossil Material

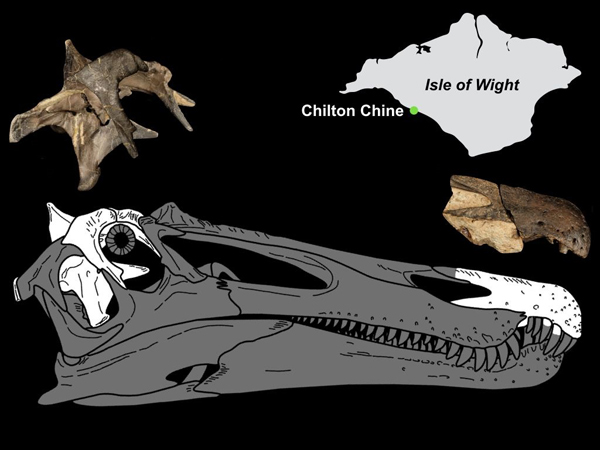

The fossil material was collected by Brian Foster from Yorkshire and Jeremy Lockwood who lives on the Isle of Wight in collaboration with several other local collectors and fossil enthusiasts, from the beach at Chilton Chine from 2013 to 2017, the rapidly eroding cliffs exposed the fossils and it is thanks to this dedicated group of amateur fossil hunters that these important specimens were saved from being washed away by the sea. More than fifty fossil bones were recovered from the site, including a partial tail which was excavated by a field team from the Dinosaur Isle Museum.

Analysis of Bones Undertaken by the University of Southampton

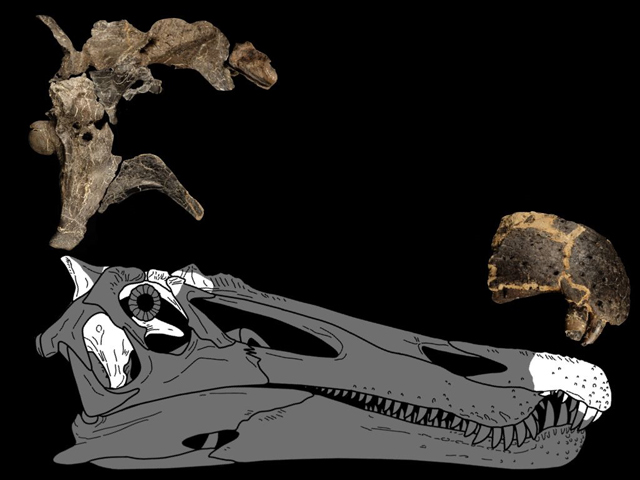

Analysis of the bones carried out at the University of Southampton and published this week in the journal “Scientific Reports” has led to the establishment of two new species of spinosaurids, which have been named Ceratosuchops inferodios and Riparovenator milnerae. Although related to Baryonyx (B. walkeri), these two new theropods might be more closely related to Suchomimus from Africa.

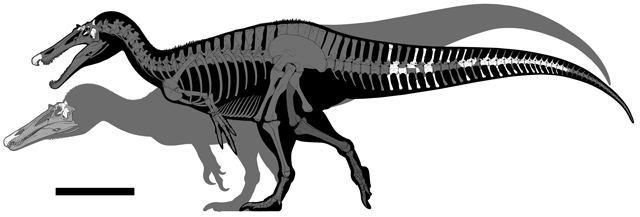

Scientists estimate that Ceratosuchops and Riparovenator were around 9 metres in length and their crocodilian-like skulls were about a metre long.

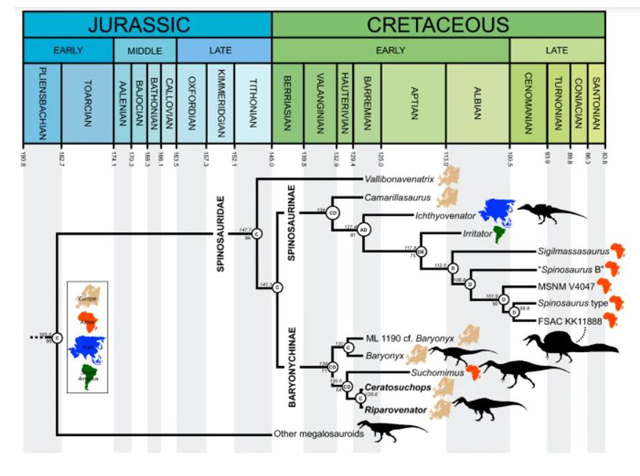

Phylogenetic and Bayesian statistical analysis suggests that Ceratosuchops and Riparovenator are sister taxa and more closely related to Suchomimus than they are to Baryonyx but work on the taxonomy of the Spinosauridae is hampered by a lack of fossil material permitting direct comparison between genera. Most palaeontologists split the Spinosauridae into two separate clades, the Spinosaurinae which includes taxa such as Spinosaurus, Ichthyovenator and Irritator and the Baryonychinae. Ceratosuchops inferodios and Riparovenator milnerae have been classified as baryonychids along with Baryonyx, Suchomimus and an as yet unnamed taxon from Portugal (ML 1190).

University of Southampton PhD student, Chris Barker, the lead author of the study commented:

“We found the skulls to differ not only from Baryonyx, but also one another, suggesting the UK housed a greater diversity of spinosaurids than previously thought.”

Ceratosuchops inferodios

The first specimen has been named Ceratosuchops inferodios, which translates from the Latin as the “horned crocodile-faced hell heron”. With a series of low horns and bumps ornamenting the brow region the name also refers to the predator’s likely hunting style, which would be similar to that of a (terrifying) heron. Herons famously catch aquatic prey around the margins of waterways but their diet is far more flexible than is generally appreciated and can include terrestrial prey too.

Riparovenator milnerae

The second new species to be named Riparovenator milnerae, translates from the Latin as “Milner’s riverbank hunter”, the species name honours the highly influential British palaeontologist Angela Milner who sadly, passed away in August. Angela, along with her colleague Alan Charig, studied and named Baryonyx (B. walkeri) and her work at the London Natural History Museum has done much to improve our understanding of theropod dinosaurs. It seems a fitting tribute to Dr Milner, for someone who was so involved in helping us to understand Baryonychids that a member of the Baryonychinae should be named in her honour.

Many Large Predators in the Ecosystem

When looking at modern food webs, the number of large predators is normally limited by the available range of prey items and other resources such as space for territories and suitable breeding sites. Whilst there are many predators on the African plains, the apex predatory position tends to be occupied by just one species – Panthera leo (lion). In the forests of India, it is another big cat that occupies the apex predator position Panthera tigris (tigers). In several dinosaur dominated ecosystems another picture emerges, where at least two, equally sized and contemporaneous large theropods seem to occupy the apex predator role. Major dinosaur-fossil-bearing geological formations have revealed that several different types of large, carnivorous dinosaur co-existed.

Examples of Multiple Types of Theropod Dinosaur Predator from a Single Geological Formation

- Dinosaur Park Formation (Canada – Upper Cretaceous) – Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus.

- Morrison Formation (Western United States – Upper Jurassic) – Torvosaurus, Allosaurus, Saurophaganax, Ceratosaurus, Marshosaurus etc.

- Lourinhã Formation (Portugal – Upper Jurassic) – Lourinhanosaurus, Torvosaurus, Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus, plus possible megalosauroids and abelisaurids.

- Huincul Formation (Argentina – early Upper Cretaceous) – Mapusaurus, Gualicho, Skorpiovenator etc.

- Shaximiao Formation (China – Middle to Upper Jurassic) – Sinraptor, Yangchuanosaurus, Gasosaurus, along with megalosauroids and other metriacanthosaurids.

Commenting on this phenomenon co-author of the scientific paper Dr David Hone (Queen Mary University) stated:

“It might sound odd to have two similar and closely related carnivores in an ecosystem, but this is actually very common for both dinosaurs and numerous living ecosystems.”

The presence of two or more spinosaurid taxa in the same geological unit (Wessex Formation) is therefore not without precedent and may in fact be typical. Furthermore, the Wessex Formation has revealed several other completely unrelated theropods that shared the environment with the spinosaurids, Eotyrannus (tyrannosauroid), the allosauroid Neovenator and at least one other, as yet unnamed large tetanuran.

Early spinosaurids may have been more generalist hunters, eating a varied diet, including fish and terrestrial prey. Only later did more specialised taxa adapted to underwater pursuit predation evolve, such as Spinosaurus. However, the degree of specialisation to an aquatic life in spinosaurids remains hotly debated and the evolutionary sequence by which aquatic adaptations came about remains unknown.

A European Origin for the Spinosauridae?

The discovery of these two new members of the Spinosauridae family and the subsequent analysis conducted by the research team supports the theory of a European origin for this family of theropods. They postulate that spinosaurs first evolved in Europe and dispersed into Asia and Western Gondwana (northern Africa and Brazil) during the first half of the Early Cretaceous. The range over which these types of dinosaurs roamed then begins to contract, by the Cenomanian faunal stage, spinosaurids are only present in north Africa.

New fossil discoveries might change our understanding of the origins and eventual extinction of these enigmatic carnivorous dinosaurs, but based on the current fossil record, rising sea levels during the Cenomanian may have reduced the number of suitable habitats available. This may have contributed to the extinction of the Spinosauridae.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the University of Southampton in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “New spinosaurids from the Wessex Formation (Early Cretaceous, UK) and the European origins of Spinosauridae” by Chris T. Barker, David W. E. Hone, Darren Naish, Andrea Cau, Jeremy A. F. Lockwood, Brian Foster, Claire E. Clarkin, Philipp Schneider and Neil J. Gostling published in Scientific Reports.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment