Theory on How T. rex tackled Triceratops for Dinner

Scientists Publish Theory of T. rex Feeding Behaviour on Triceratops

It seems that most dinosaur films and television programmes feature a battle between meat-eating and plant-eating dinosaurs. Viewers can’t get enough of these huge, extinct reptiles battling one another and now a team of researchers at the Museum of the Rockies (Montana, United States) have published a rather gory paper explaining how Tyrannosaurus rex may have fed on Triceratops. The scientists postulate that this tyrannosaur ripped the head off its victim so that it could feast on the large neck muscles that were in place immediately behind the Triceratops bony neck frill.

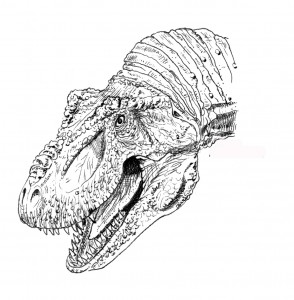

Tyrannosaurus rex

Denver Fowler at the Museum of the Rockies and his colleagues studied a total of eighteen Triceratops specimens from Montana’s Hell Creek Formation, some of which showed the characteristic Tyrannosaurus bite marks. There are a number of Triceratops skulls in the fossil record that show signs of tooth marks and punctures made by the characteristic “D-shaped” teeth of a tyrannosaurid. In a paper presented at the recent annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology, the team graphically illustrated how a dead Triceratops may have been decapitated by a feeding Tyrannosaurus rex.

Gruesome Theory Concerning Tyrannosaurid Feeding Behaviour

Picture credit: Mike Fredericks

Signs of injuries and disease in fossils is known as pathology. Palaeontologists have studied the fossilised bones of both the plant-eating Triceratops and the meat-eating tyrannosaurids and there is a lot evidence to support the theory that T. rex attacked and fed upon this particular horned dinosaur. However, in this new study the researchers were interested in working out what the marks and scars on the bones of this particular horned dinosaur said about the way in which a tyrannosaur may have fed upon a Triceratops carcase.

The Museum of the Rockies

The Museum of the Rockies team were intrigued to discover that many of the puncture and pull marks were on the bony neck frill of the fossil specimens they studied. Triceratops had a very large skull, it was protected by three horns on its face, (the name Triceratops means “three horned face”). It had a short nose horn and two further, much larger horns over the eyes. These horns could grow to be more than a metre long in mature adults. Scientists have long speculated that the horns and frills of ceratopsians performed many functions. They may have been brightly coloured, an aid to visual communication amongst herd members. The horns and frills may have also been used in intraspecific combats, for example, two Triceratops fighting together over mates or social status. These facial ornaments were also defensive structures, very useful when you share the same environment as thirteen-metre-long tyrannosaurs with an ability to swallow up to seventy kilogrammes of meat in one mouthful.

T. rex Feeding – A Scenario

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The skull of Triceratops was very heavy and in comparison to the rest of the body it did not have a lot of meat on it. The neck frill would not have offered a lot of nutrition, so why the bite and pull marks?

A Study of Ceratopsian Skulls

An analysis of the fossilised Triceratops skull material revealed deep, parallel groves on the neck frill, suggesting that a feeding Tyrannosaurus rex may have used its immensely strong jaws and neck muscles to pull on the frill in order to reposition the carcase for feeding or indeed to move the corpse. Many predators today; after they have made a kill attempt to drag the corpse of their victim to a concealed place so that they can feast in peace without being disturbed by scavengers or worse still, a bigger predator coming along and chasing them away from their dinner. Leopards for example have been known to drag the body of a gazelle up into a tree so they can feed without being disturbed by lions. Perhaps T. rex attempted to move their victims so that they could eat without the risk of being attacked by other tyrannosaurs. However, the prospect of dragging a seven tonne “dead weight” any distance would have been quite daunting and it would have wasted a lot of energy, perhaps the pull marks indicate where the body was torn apart – a sort of how to eat a Triceratops – one chunk at a time scenario.

Tyrannosaurus rex Feeding Habits

If T. rex was attempting to reposition its prey then the scientists speculate that the bony neck frill would have prevented the carnivore from accessing the large muscles on the neck of Triceratops. The team have proposed that this nasty predator probably used its teeth and jaws to pull on the frill in an effort to get at the meat behind the frill.

The gruesome conclusion made by the palaeontologists is that the easiest way to get to the large neck muscles is to pull the head right away from the body. In this academic paper, it is postulated that T. rex ripped the heads of its Triceratops victims.

Further evidence to support the “heads-ripped-off-Triceratops” theory was found by the scientists when they examined the joint that attaches the neck to the skull. This ball and socket joint, known as the occipital condyles showed signs of bite marks on the anterior surface. The scientists concluded that such marks could only have been made if the head had been removed from the body.

The problem with this rather gruesome area of research is that we cannot rely on observations using extant animals (animals alive today) to support this theory. The Tyrannosaurus rex versus Triceratops predator prey relationship involves a biped attacking a quadruped. As we humans (H. sapiens) are the only true biped amongst the Mammalia alive today finding evidence to support this theory in the natural world is very difficult. Wolves attack horned bison but observations of a wolf pack’s behaviour suggests that they avoid attacking the head and neck region and prefer to try to bring down their quarry by attacking the hind legs. A wolf weighs fifty times less than a large bison, whereas an adult T. rex and an adult Triceratops were much more evenly matched in terms of body mass. Scientists do not know whether tyrannosaurs were solitary hunters or pack animals, if they were pack animals then this would suggest differences in hunting and feeding strategies.

Moreover, there are a number of Triceratops skulls preserved in the fossil record for palaeontologists to study. Other parts of the Triceratops anatomy, the front legs for example are rarely found in the fossil record. It has been speculated that the front legs rarely fossilised as this part of the body of a Triceratops was readily consumed as the carcase was broken up.

Bite Marks on Neck Frills

The Museum of the Rockies team point to the fact that the bite marks on many of the neck frills show no signs of healing. This, they suggest indicates that these injuries occurred after the Triceratops had expired and provide evidence of feeding behaviour. Unfortunately, an attack by a tyrannosaurid as it attempted to bring down its prey, would have resulted in extensive bite marks too. If the attack proved fatal then these wounds which were inflicted during the fight between these two protagonists could be easily confused with those pathologies caused as a result of feeding.

For models and replicas of Tyrannosaurus rex, Triceratops and other famous dinosaurs: Nanmu Studio Jurassic Series Dinosaurs.

It seems that we may never know the exact methods used by tyrannosaurs to maximise their feeding with the minimum of effort when it came to eating a Triceratops, however, this new research “heads” us in an interesting direction.

The scientific paper: “How to eat a Triceratops: large sample of toothmarks provides new insight into the feeding behavior of Tyrannosaurus” by D. Fowler, J. Scannell, M. Goodwin and J. Horner published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.