Hadrosaurs – Tough Teeth for Top Chewing According to New Research

Research into Hadrosaur Dentition Provides Clue to the Group’s Success

One of the most successful groups of large, land animals known to science are the Hadrosauridae, a group of ornithischian (bird-hipped), plant-eating dinosaurs that evolved from the iguanodontids during the Cretaceous geological period. These animals evolved into many families and genera, some species grew up to twelve metres in length or more and they dominated terrestrial ecosystems across the Northern Hemisphere up until the demise of the Dinosauria 66 million years ago. A new study examining the dentition of hadrosaurs, suggests their teeth were one of the reasons for their evolutionary success.

Dentition of Hadrosaurs

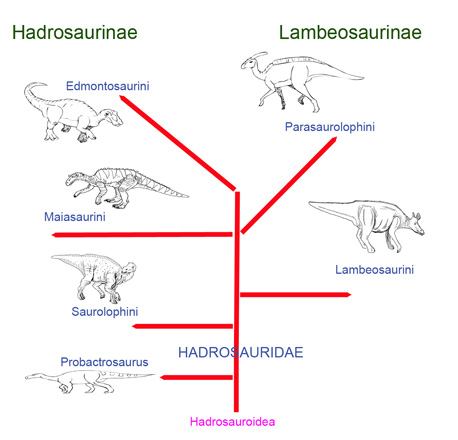

This type of dinosaur, commonly called “duck-billed” dinosaurs as they all had horny beaks is classified into two major taxons – the Lambeosaurinae and the Hadrosaurinae. Lambeosaurs, dinosaurs such as Parasaurolophus, Corythosaurus and Olorotitan had hollow, ornate head crests. The Hadrosaurinae, animals such as Gryposaurus, Maiasaura and Edmontosaurus lacked the often flamboyant crest. Instead, these dinosaurs had flat, crestless heads or their snouts were ornamented with bony lumps or solid crests.

Taxonomic Relationships in the Hadrosauridae

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Differences Between the Clades

There are other differences between these two clades of dinosaurs. For example, the Hadrosaurinae generally had broader jaws and wider beaks than their Lambeosaurinae cousins. This suggests different feeding habits with the narrow-beaked lambeosaurs being more selective feeders. Both types of hadrosaur had many hundreds of closely packed, diamond shaped teeth in their jaws, some specimens had over 1,400 individual teeth in their mouths. These teeth formed a “dental battery”, interlocked teeth to form a very efficient grinding surface to help these animals tackle tough plant material. The upper and lower tooth batteries were angled so that when the mouth was closed the teeth formed a natural grinding surface. For many years palaeontologists had known that these animals were very efficient processors of plant food, perhaps a clue to this groups’s success but new research proposes that the structure of the teeth themselves made these dinosaurs much more effective consumers of plants than most of today’s grazers.

To view models and replicas of hadrosaurs (lambeosaurines and Saurolophinae): Ornithischian Dinosaur Models (Safari Ltd).

Super Efficient Plant-Eaters

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

A team of American scientists led by biologist Gregory Erickson of Florida State University (Tallahassee), have been testing the grinding capabilities of eighty-five-million-year-old duck-billed dinosaur teeth and examining their internal structure. Their research shows that the hadrosaurs evolved extremely sophisticated teeth, more sophisticated than modern mammalian herbivores such as bison, horses and elephants.

Using teeth supplied by the American Museum of Natural History (New York), the research team created models of the jaws of these types of dinosaurs and subjected the teeth to diamond abrasion to simulate wear on the tooth surface as a result of grinding up plant material. The teeth were then examined under light and electron microscopes and the degree of wear calculated.

Hadrosaur Dentition

Picture credit: D. Gregory Erickson

The study demonstrates that unlike most mammalian molars and pre-molars which are composed of four major tissues that wear at different rates, creating coarse, roughened surfaces to help break down tough plants, the duck-bills evolved a six tissue dental composition which improved the teeth’s ability to grind up food.

Tough, strong teeth designed to tackle plants has evolved repeatedly in the ungulates and other mammal groups. However, a similar innovation in dental complexity occurred much earlier in the history of life on Earth, with the hadrosaurs. Most reptilian teeth are not as complex, it seems that as the iguanodontids gave rise to the hadrosaurs so the teeth of these animals evolved into extremely efficient grinders. The external layer of enamel being supported by layers of other tissue such as dentine. Importantly, the researchers also discovered that the way tissues were distributed varied substantially within each individual tooth. Each tooth in the dental battery would assume a different function as the morphology and the grinding surface of the tooth changed as it became worn. Different surfaces would be exposed as the teeth migrated across the grinding and chewing surface of the jaw, before eventually falling out to be replaced with new teeth that emerged from the jawline.

The morphology and structure of the teeth would have enabled these herbivores to grind up tough plants such as horsetails, ferns, conifer needles and the newly evolved flowering plants. Most reptiles have much more simple teeth structures and the scientists are not sure how such dentition evolved. The lack of transitional fossils between iguanodontids and hadrosaurs is hindering the team’s progress as they search for answers in the fossil record.

Referring to hadrosaurs as “walking pulp mills“, Gregory Erickson and his research colleagues have declared the duck-billed teeth lined jaws as one of the most sophisticated grazing and grinding mechanisms ever to evolve in terrestrial mega herbivores. Their teeth are more complex and better adapted to grinding than most of the large plant-eating mammals found today.