The Amazing Westbury Pliosaur – 8-metre Long Beast with Arthritis

Evidence of Arthritis in Pliosaur’s Lower Jaw

A team of researchers studying the fossilised jawbones of a huge Jurassic marine predator known as the Westbury pliosaur, have found evidence that the monster (believed to be an elderly female), suffered from arthritis in its lower jaw.

A new study by scientists based at the University of Bristol (England) and published in the scientific journal “Palaeontology” has found evidence of a degenerative condition similar to human arthritis in the jaw of a pliosaur, a huge predator that lived 150 million years ago.

Westbury Pliosaur

The two-metre lower jaw, with some of its twenty-centimetre-long teeth still in-situ, shows signs of an arthritic condition, such pathology is extremely rare in fossilised marine reptiles from the mid-Mesozoic. The pliosaur remains, were found in Westbury, Wiltshire and is now part of the vertebrate fossil collection kept at the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery.

Pliosaurs, otherwise known as short-necked plesiosaurs; are believed to have evolved from the Triassic nothosaurs. These marine reptiles had long, narrow jaws, two pairs of broad flippers and some of these creatures evolved into the largest known predators in the fossil record. Lengths in excess of fifteen metres have been suggested for some genera. The Westbury monster was more than eight metres long and was top of the food chain in the warm, shallow tropical sea that this leviathan patrolled. However, as this animal grew older it suffered from a painful lower jaw showing signs of deterioration that is similar to arthritis in our own species.

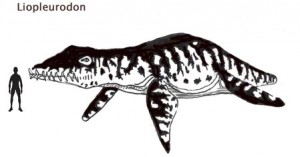

A Drawing of a Marine Reptile – Liopleurodon ferox?

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

To view models and replicas of pliosaurs and other prehistoric creatures: CollectA Deluxe Prehistoric Life Models.

University of Bristol scientist, Dr Judyth Sassoon, became fascinated by the specimen when she saw it in the museum’s collections and studied it for her MSc research project. During her studies, she noticed that it had the signs of a degenerative condition similar to human arthritis, that had eroded its left jaw joint, displacing the lower jaw to one side. The condition may have been painful, but evidently this marine reptile lived with a crooked jaw for many years, as indicated by marks on the lower jaw bone where the teeth from the upper jaw impacted with the lower jaw as the creature bit down. Modern day crocodiles and alligators can suffer from similar conditions, their elongated jaws can also be damaged as these creatures hunt, however these reptiles can survive for many years so long as they are able to catch prey.

An Old Female Pliosaur

There are several signs on the skeleton to suggest that the animal could have been an old female who had developed the condition as part of the aging process. The pliosaur’s large size, and the fused skull bones, suggest maturity. It is identified, very tentatively, as possibly female because its skull crest is quite low, some scientists believe that male pliosaurs had larger, more pronounced crests on their heads, but spotting the girl pliosaurs amongst the boy pliosaurs is still a topic that is hotly debated amongst palaeontologists.

Commenting on the pathology, Dr Sassoon stated:

“In the same way that aging humans develop arthritic hips, this old lady developed an arthritic jaw, and survived with her disability for some time. But an unhealed fracture on the jaw indicates that at some time the jaw weakened and eventually broke. With a broken jaw, the pliosaur would not have been able to feed and that final accident probably led to her demise.”

Professor Mike Benton, a collaborator on the project, added:

“You can see these kinds of deformities in living animals, such as crocodiles or sperm whales and these animals can survive for years as long as they are still able to feed. But it must be painful. Remember that the fictional whale, Moby Dick from Herman Melville’s novel, was supposed to have had a crooked jaw!”

The Westbury Pliosaur (Lower Jaw with teeth fragments)

Picture credit: Bristol University

The picture above shows the pliosaur jaws, with Dr Judyth Sassoon. The jawbone deformity can be seen on the left lower jaw in the area opposite the Doctor’s wrist.

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented that they had seen similar bone deformities in the fossils of many dinosaurs, for example the toe bones of a hadrosaur from Upper Cretaceous deposits of Alberta (Canada) that showed signs of a painful joint condition, however, they were not aware of any other example of this sort of pathology being found in the fossils of a Jurassic marine reptile.

The spokesperson went onto speculate how the condition may have arisen in the pliosaur in the first place:

“Pliosaurs are believed to have been ambush predators, using their huge paddles to propel themselves at their intended victims at great speed, before grasping their unfortunate prey with their immensely strong jaws. Enormous forces would have been involved and it is possible that the lower jaw may have been damaged at some time in the creature’s life which enabled the arthritic condition to take hold.”

The pliosaur from Westbury is an amazing example of how the study of disease (palaeopathologies) in fossil animals can help us to reconstruct an extinct animal’s life history and behaviour and to show that even a Jurassic killer could succumb to the diseases of old age.

Everything Dinosaur would like to thank Bristol University for the information contained in this article.