A superbly preserved and almost complete specimen of the pterosaur Tupandactylus navigans has enabled researchers to get a better understanding of the body of this Brazilian flying reptile. The skull too, with its exquisite preservation has provided new data on the amazing super-sized sagittal crest associated with this genus.

Confiscated in a Police Raid

The fossil specimen (number GP/2E 9266), was confiscated in a police raid at Santos Harbour, São Paulo State (Brazil), along with several other beautifully well-preserved fossils. Unfortunately, illegal fossil collection and sale of specimens on the black market is an increasing problem in Brazil. However, the successful raid prevented this hugely significant pterosaur fossil from ending up in the hands of a private collector.

The specimen is now housed at the Universidade de São Paulo (Brazil) and most of the researchers involved in the scientific paper are also based in Brazil, except for Octávio Mateus (Museu da Lourinhã, Portugal). Writing in the on-line, open access journal PLOS One, the scientists conclude that this specimen is the best-preserved tapejarid skeleton discovered to date. Their analysis has shed new light on the anatomy of this Tapejaridae family.

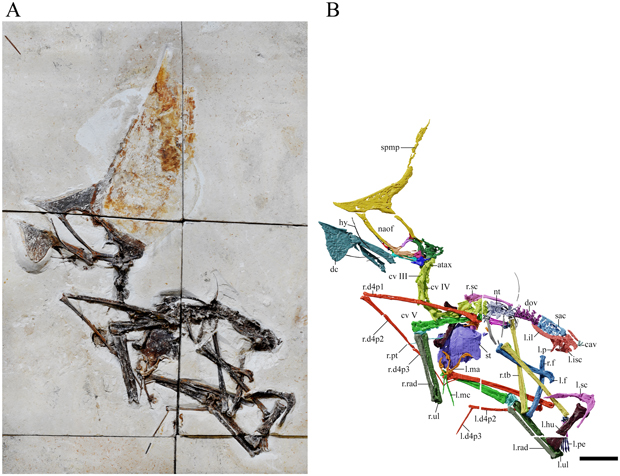

CT Scans

The pterosaur fossil is comprised of six limestone slabs. As this fossil was collected illegally, its provenance is unknown. However, by studying the yellow-stained, laminated limestone matrix, the research team were able to confidently assign the fossil to the Aptian-aged Crato Formation. The fossil took a trip to the local hospital in São Paulo, to enable CT scans to be undertaken. The subsequent three-dimensional models generated enabled the scientists to reconstruct the body of Tupandactylus for the first time. Prior to the discovery of this fossil, most Brazilian tapejarids had been described based on isolated skull bones.

Tupandactylus and a Remarkable Head Crest

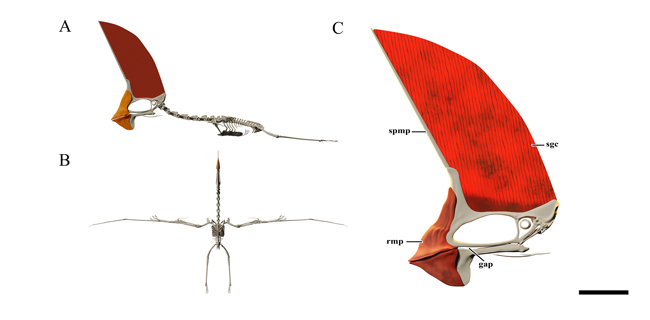

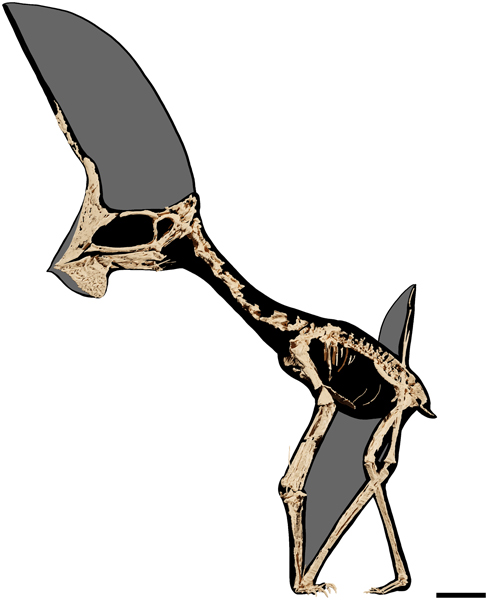

Soft tissue from the huge crest on the top of the head, extends to more than five times the actual height of the skull. Analysis of the crest enabled the research team to confirm differences between Tupandactylus navigans and the closely related T. imperator. Specimens of T. navigans tend to be smaller than T. imperator and it had been speculated that just one species was represented with the differences between T. imperator and T. navigans being explained by sexual dimorphism. Thanks to the exquisite preservation of this fossil specimen the research team were able to identify several anatomical traits that support the idea that Tupandactylus navigans and Tupandactylus imperator are indeed separate species.

Different colour patterns seen in the sagittal crest do not represent fossilisation of any colour patterning but may have occurred due to oxidation of the material. However, a more detailed analysis of the soft tissues associated with GP/2E 9266 is currently being undertaken.

Tupandactylus navigans

Tupandactylus navigans was named and scientifically described in 2003 based on a study of two fossil skulls (Frey, Martill and Buchy). At the time, it was postulated that the huge head crest could have been used as a sail to help with flight stability and assist with aerial propulsion. For this structure to work in this way, the neckbones would have had to be robust, relatively short and supported by powerful tendons to combat stresses imposed on the neck. With an almost complete, articulated skeleton to study, the scientists led by Victor Beccari (Universidade de São Paulo), discovered that this pterosaur had a long neck, long limbs and relatively short wings (estimated wingspan 2.7 metres).

The enormous crest probably did not play a role in aiding powered flight. Such a huge structure may well have hindered this pterosaur’s aerial abilities.

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“The sagittal crest of Tupandactylus may have evolved due to sexual selection pressure, females showing a bias towards males with larger crests. The crest may have been used for display or to denote maturity, status or fitness for breeding. Many living birds sport crests, wattles and other structures, perhaps adult T. navigans sacrificed some aerial ability by growing enormous crests in a bid to attract mates.”

For models and replicas of pterosaurs and other prehistoric creatures: Prehistoric Animal Models.

Spotting a Notarium

The front five dorsal vertebrae form a notarium which helps brace the chest and counter the stresses on the torso created by the flapping of the wings. This structure is found in living birds and some types of pterosaur but this is the first time, as far as Everything Dinosaur team members are aware, that a notarium has been identified in a tapejarid.

he scientific paper: “Osteology of an exceptionally well-preserved tapejarid skeleton from Brazil: Revealing the anatomy of a curious pterodactyloid clade” by Victor Beccari, Felipe Lima Pinheiro, Ivan Nunes, Luiz Eduardo Anelli, Octávio Mateus and Fabiana Rodrigues Costa published in PLOS One.

Leave A Comment