Scientists Solve Puzzle of Where the Dinosaur-killing Asteroid Came From

Researchers from the Department of Space Studies at the Southwest Research Institute (Boulder, Colorado), have developed a dynamic model to predict the origin of the extra-terrestrial body that smashed into our planet 66 million years ago. This colossal impact event played a significant role in the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs.

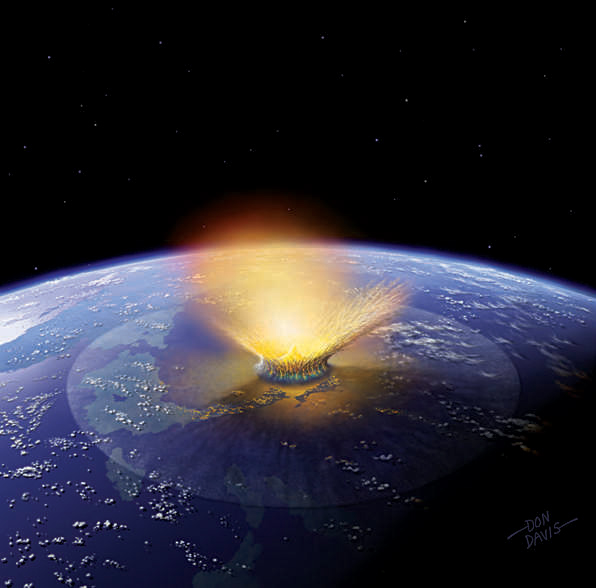

An artist’s impression of the bolide about to impact with the Gulf of Mexico 66 million years ago. Picture credit: Chas Stone.

Picture credit: Chas Stone

From the Outer Half of the Main Asteroid Belt

The research suggests that the dinosaur-killing asteroid originated from the outer half of the main asteroid belt between Mars and the gas giant Jupiter. It had been thought that this region of space did not produce many impactors (bodies that crash into other planets, moons etc). The paper published in “Science Direct” concludes that the processes that deliver large asteroids to Earth from that region occur at least ten times more frequently than previously thought and that the composition of these bodies match what we know of the dinosaur-killing impactor.

The Southwest Research Institute team consisting of lead author Dr David Nesvorný, Dr William Bottke and Dr Simone Marchi used sophisticated computer models of asteroid evolution combined with observations of known asteroids to investigate how frequently so-called Chicxulub events might occur. Around 66 million years ago an extra-terrestrial bolide estimated at around 10 kilometres in diameter smashed into the Gulf of Mexico (Yucatan peninsula). This impact event devastated life on Earth and formed the Chicxulub crater – which is over 150 kilometres across.

Commenting on the purpose of their research, Dr William Bottke explained that two very important questions remained unanswered:

“What was the source of the impactor? How often did such impact events occur on Earth in the past?”

Picture credit: SwRI and Don Davis

The Search for the Source of the Dinosaur-Killing Asteroid

Using recently published research on the composition of the Chicxulub crater the researchers identified that the extra-terrestrial body that smashed into Earth had a similar chemical signature to the carbonaceous chondrite class of meteorites. Intriguingly, whilst carbonaceous chondrites are common amongst the many mile-wide bodies that approach the Earth, none today are close to the size needed to produce the Chicxulub impact with any kind of reasonable probability.

Dr Nesvorný explained that this finding sent the team on a hunt into space to find the likely source of the bolide that collided with Earth with such catastrophic consequences for about 75% of all terrestrial lifeforms.

He commented:

“We decided to look for where the siblings of the Chicxulub impactor might be hiding.”

The team turned to the NASA’s Pleaides Supercomputer and modelled the trajectories of 130,000 asteroids, examining how gravitational kicks from the planets might push these objects into orbits near to Earth. The researchers found that their computer simulations predicted Earth impacts from asteroids originating from the outer half of the asteroid belt ten times more frequently than previously thought.

Picture credit: BBC with additional annotation by Everything Dinosaur

They calculated that asteroids in excess of 10 kilometres in diameter hit Earth once every 250 million years or so.

This suggests that the non-avian dinosaurs and the other organisms that became extinct 66 million years ago, were very unlucky. Fortunately, in deep geological time, such catastrophic Earth impacts remain rare.

Commenting on the importance of this new research, Dr Nesvorný added:

“This work will help us better understand the nature of the Chicxulub impact, while also telling us where other large impactors from Earth’s deep past might have originated.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the Southwest Research Institute in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Dark primitive asteroids account for a large share of K/Pg-scale impacts on the Earth” by David Nesvorný, William F. Bottke and Simone Marchi published in Science Direct.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.