Sizing Up Early Dinosaurs – Variation an Evolutionary Advantage?

For Coelophysis Variety Might Have Been the Spice of Life

Scientists from Virginia Tech University have concluded that early dinosaurs had a wide variety of growth patterns, a trait that may have helped species survive extinction events ultimately assisting the Dinosauria to establish themselves as the dominant, large terrestrial fauna. The study, published in the academic journal “The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences”, focuses on one early theropod, Coelophysis (pronounced: See-low-fy-sis), and the scientists conclude that a single dinosaur species contained a huge amount of diversity in terms of the size that the animals grew to.

Studying Coelophysis

This sets dinosaurs apart from birds, which tend to be much more uniform in terms of their growth rates and sizes within a single species. A species that contained a broad range of different sized individuals may have had an advantage during hard times or when a sudden catastrophe occurred. This ontogenetic variation may have helped dinosaurs like Coelophysis survive the harsh environment at the end of the Triassic some 210 to 201 million years ago, a time when a large number of other terrestrial reptile species became extinct.

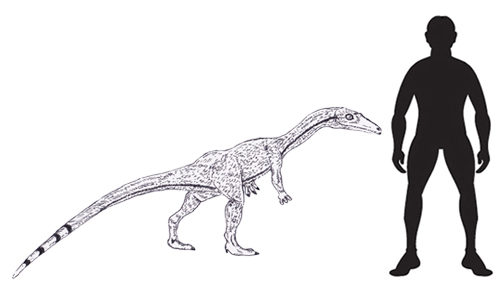

Study of the Theropod Coelophysis May Provide a Clue to the Success of Dinosaurs

Picture credit: Matt Celeskey

A Race for Supremacy Across Pangaea

The end Permian extinction event devastated terrestrial ecosystems and the early dinosaurs rapidly evolved and radiated to take advantage of vacated ecological niches. During the Triassic, a wide variety of land animals competed with each other – cynodonts, dicynodonts, rauisuchids, phytosaurs and dinosaurs. Scientists have put forward several theories as to why the Dinosauria eventually rose to become the dominant megafauna. This new research, conducted by Christopher Griffin and Sterling Nesbitt (Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech), looked at the variation in growth patterns in a mass death fossil assemblage of Coelophysis, a flock of fast-running, carnivorous dinosaurs that died together in a flood some 208 million years ago, in present-day New Mexico (Ghost Ranch).

Hundreds of individuals were buried together, ranging from youngsters, to sub-adults to fully grown animals. In total, the researchers examined the fossilised remains of 174 specimens, housed in museums across America.

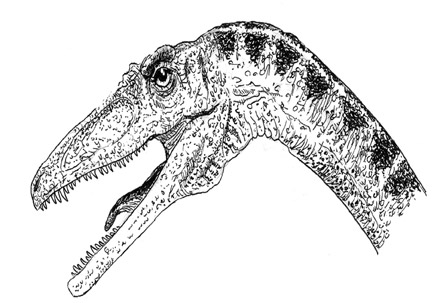

An Illustration of the Head of Coelophysis

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Explaining their results, lead author, Christopher Griffin stated:

“We found that the earliest dinosaurs had a far higher level of variation in growth patterns between individuals than crocodiles and birds, their closest living relatives. Not only were there many different pathways to grow from hatchling to adult, but there was an incredible amount of variation in body size, with some small individuals far more mature than some larger individuals, and some large individuals more immature than we would guess based on size alone.”

Ontogenetic Sequence Analysis

A technique called ontogenetic sequence analysis was used to assess the growth of the Coelophysis fossil assemblage, this data set was compared to two extant birds and one crocodile species, animals alive today that are closely related to extinct dinosaurs. The birds (Aves) are the fastest growing terrestrial vertebrates, anyone who has observed nesting garden birds can see how, within a few weeks, the hatchlings are almost the same size as their parents.

Birds develop unlike all other living archosaurs. As part of this postnatal development, birds possess a low amount of intraspecific variation, put simply, one bird such as a blackbird (Turdus merula) grows at much the same rate as other members of its species and there is little size variation in populations. The Coelophysis flock shows a very different growth rate with a wide variety of adult sizes. When did this low variation in body size amongst archosaurs evolve? By studying the extensive fossil collection of one species of non-avian, extinct animal (Coelophysis), scientists hope to pinpoint this transition in Mesozoic theropods.

Coelophysis Study Sheds Light on the Evolution of Growth Rates Amongst the Theropoda

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

To view models of Coelophysis and other prehistoric animals: Wild Safari Prehistoric World Models and Figures.

Analysing the Fossil Bones of Coelophysis

Geosciences Master’s student Christopher Griffin went onto state:

“As these animals grew, muscle attachment scars formed on the limb bones, and the bones of the ankle, hips, and shoulder fused together, similar to how the skull bones of a human baby fuse together during growth. Fossils of even a single partial skeleton of an early dinosaur are exceptionally rare, so to have an entire group of a single species that lived and died together provided an unparalleled opportunity to study early dinosaur growth like never before.”

Variation Lost in More Derived Theropods

The team concluded that this high variation in early dinosaurs as demonstrated by the Coelophysidae was lost in more derived theropod dinosaurs such as Allosaurus of the Late Jurassic and Late Cretaceous tyrannosaurids. This intraspecific high variance could have contributed to the rise of the Dinosauria during the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event.

Assistant professor Sterling Nesbitt added:

“Large variation in early dinosaurs may have allowed them to survive harsh environmental challenges like dry climate and high levels of carbon dioxide. Understanding why dinosaurs were so successful has been a great mystery, and high variation may be one of the characteristics of dinosaurs that led to their success. However, it’s difficult to determine whether this trait evolved in response to the environment or was simply a stroke of luck that allowed these dinosaurs to survive and thrive and become the most dominate vertebrates on Earth for 150 million years.”

Not Down to Differences in Size Between Males and Females

Variation in those species of early dinosaurs which have a more substantial fossil record had been put down to sexual dimorphism in the past. However, this new study, which focused on growth rate analysis as conferred by the degree of bone fusion and muscle scar evidence on the fossilised bones, did not find data to support that the fossil assemblage growth rates were solely down to differences in the adult size of males and females.

Steve Brusatte, a palaeontologist from the University of Edinburgh, who has undertaken research into the growth rates of other types of theropods, such as tyrannosaurs, commented:

“Studies like this are a perfect demonstration of how fossils can help us understand the evolution of peculiar features and behaviours of modern animals. How dinosaurs grew may have been both the key to their early success and the reason that one particular unique subgroup, the birds, survives today.”

The scientific paper: “Anomalously High Variation in Postnatal Development is Ancestral for Dinosaurs but Lost in Birds”.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s award-winning website: Everything Dinosaur.