Fossilised Bacteria Shed Light on Life Before Oxygen

Ancient African Rocks Provide Evidence of Life Before Oxygen

The fossils of ancient bacteria that existed in deep water environments during the Neoarchean Era some 2.52 billion years ago, have been identified by an international team of researchers. They don’t represent the oldest known life on our planet, recently, Everything Dinosaur published an article on some new research that postulates that microbial colonies existed on Earth some 3.7 billion years ago*, but these South African fossils may represent the oldest evidence of a bacteria capable of oxidising sulphur (within the Class Gamma Proteobacteria), found to date.

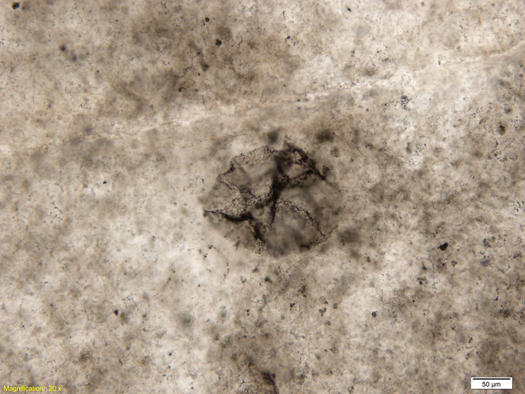

A Highly Magnified Image of a Fossilised Bacteria

Picture credit: Andrew Czaja

This discovery is significant as it sheds light on a time in Earth’s history, when, essentially, all the microbial forms that exist today had probably evolved, but the fossil record for their existence is particularly sparse.

Writing in the journal of the Geological Society of America, the researchers which include scientists from the University of Cincinnati and the University of Johannesburg, report on large, organic, smooth-walled, spherical microfossils representing organisms that lived in deep water, when our planet’s atmosphere had less than one-thousandth of one percent of the oxygen we have today.

Microscopic Life in the Archaean

The research team discovered the microscopic fossils preserved in black chert that had been laid down at the bottom of a deep ocean, in the Griqualand West Basin of the Kaapvaal craton of South Africa (Northern Cape Province).

Geologist Andrew Czaja (University of Cincinnati), explained that this part of South Africa was one of the few places in the world where rocks of this great age were exposed. The fossils are very significant as they represent bacteria surviving in a very low oxygen environment, the bacteria existed prior to “Great Oxygenation Event”, sometimes referred to as the GOE, a period in Earth’s history from about 2.4 billion to 2.2 billion years ago, when water-borne cyanobacteria (blue-green bacteria), evolved photosynthesis and as a result, oxygen was released into the atmosphere. More oxygen in our atmosphere helped drive the evolution of complex organisms, eventually leading to the development of multi-cellular life.

Commenting on this research Assistant Professor Andrew Czaja stated:

“These are the oldest reported fossil sulphur bacteria to date and this discovery is helping us reveal a diversity of life and ecosystems that existed just prior to the Great Oxidation Event, a time of major atmospheric evolution.”

Radiometric Dating and Geochemical Isotope Analysis

Radiometric dating and geochemical isotope analysis suggest that these fossils formed on an ancient seabed more than one hundred metres down. The bacteria fed on sulphates that probably originated on the early super-continent Vaalbara (a landmass that consisted of parts of Australia and South Africa). With the fossils having been dated to 2.52 billion years ago, the bacteria were thriving just before the GOE, when shallow water bacteria began creating more oxygen as a by-product of photosynthesis.

Czaja’s fossils show the Neoarchean bacteria in plentiful numbers while living within the muddy sediment of the seabed. The assistant professor and his co-researchers postulate that these early bacteria were busy ingesting volcanic hydrogen sulphide, the molecule known to give off a rotten egg smell, then emitting sulphate, a gas that has no smell.

This is the same process that goes on today as extant microbes recycle decaying organic matter into minerals and gas. The team surmise that the ancient oceanic bacteria are likely to have consumed the molecules dissolved from sulphur rich minerals that came from the land rocks associated with Vaalbara or from volcanic rocks on the seabed.

Andrew Czaja Points to the Rock Layer where the Fossil Bacteria was Found

Andrew Czaja (University of Cincinnati), points to the rock layer from which fossil bacteria was collected.

Picture credit: Aaron Satkoski

Sizeable Ancient Bacteria

These fossils occur mainly as compressed and flattened solitary shapes that resemble a flattened, microscopic beach ball. They range in size from 20 microns (µm), about half the thickness of a human hair, up to a whopping 265 µm, that’s some very large bacteria, about forty times bigger than a human red blood cell, making the fossils exceptionally large for an example of bacteria. The research team hypothesis that these ancient bacteria were similar in habit to the modern, equally large-sized bacteria Thiomargarita, which lives in oxygen-poor, deep water environments.

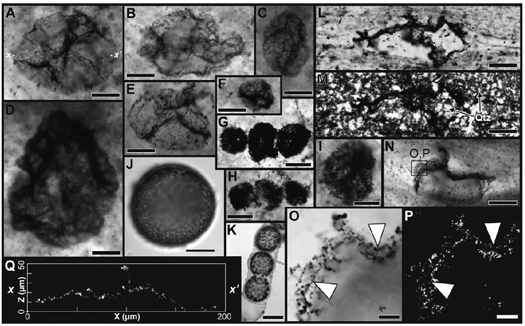

Described as being morphologically similar to Proterozoic and Phanerozoic acritarchs and to certain Archaean fossils interpreted as possible blue-green bacteria (cyanobacteria), these fossils are the oldest reported sulphur processing bacteria described to date. They reveal that microbial life was diverse as early as 2.5 billion years ago and provide further evidence that organisms can thrive in very low oxygen environments. This may have implications for astronomers as they search for evidence of life on other planets and moons within our solar system.

Images of the Microstructures (Dark, Round Spots within Ancient Rocks)

Images of microstructures that have physical characteristics with the remains of spherical bacteria.

Picture credit: Andrew Czaja

*To read Everything Dinosaur’s recently published article (September 2016), about the possible identification of evidence of microbial colonies in strata some 3.7 billion years old: 3.7-Billion-Year-Old Microbes.

The scientific paper: “Sulfur-oxidizing Bacteria prior to the Great Oxidation Event from the 2.52 Ga Gamohaan Formation of South Africa”, published in “Geology” the journal of the Geological Society of America.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s website: Everything Dinosaur.