Limusaurus – Dinosaur Species Lost Teeth as it Grew Up

Limusaurus – Shed Teeth as it Grew

An international team of scientists, including researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and George Washington University (United States), have made a remarkable discovery regarding the early Late Jurassic Chinese theropod dinosaur Limusaurus (L. inextricabilis). As this dinosaur grew it gradually shed its teeth and a beak formed. This is the only example of this known from the Class Reptilia. No other reptile extinct or otherwise, lost its teeth and formed a beak after birth. This research could shed new light on how birds are related to dinosaurs as well as specifically addressing the process of the evolution of beaks in the Aves (birds).

Limusaurus inextricabilis

The researchers propose that young dinosaurs were carnivorous, eating insects and small vertebrates, whilst the adults were most likely herbivores.

Scientific Paper Explores the Ontogeny of the Ceratosaurian Theropod Limusaurus

Young Limusaurus dinosaurs were carnivores as they grew up they probably switched to a herbivorous diet.

Picture credit: Yu Chen

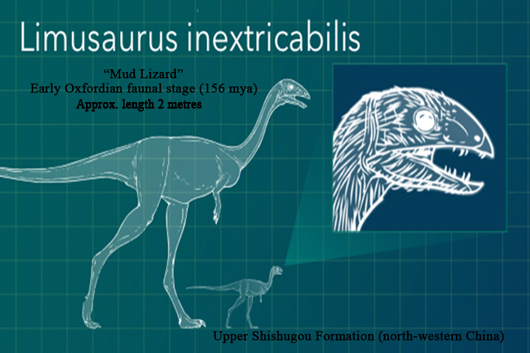

Limusaurus “Mud Lizard”

Limusaurus was named and scientifically described in 2009, from a series of fossils found in ancient “death traps”, muddy mires which the small, bipedal dinosaurs became trapped in and unable to free themselves, (the binomial name means “mud lizard that could not extract itself”, a reference to how this group of ceratosaurian dinosaurs met their fate. A number of specimens are known ranging from youngsters, estimated to be around twelve months of age, to juveniles, sub-adults and more mature individuals estimated to have been approximately ten years old when they died.

Josef Stiegler, a graduate student at George Washington University and co-author of the scientific paper published in the journal “Current Biology” stated:

“For most dinosaur species, we have few specimens and a very incomplete understanding of their developmental biology. The large sample size of Limusaurus allowed us to use several lines of evidence including the morphology, micro-structure and stable isotopic composition of the fossil bones to understand developmental and dietary changes in this animal.”

Nineteen Specimens – Placed into Six Ontogenetic Stages

In total, the team had nineteen fossilised skeletons to study. Anatomical comparisons and CT scans of the jaws and skull helped the scientists identify six distinct ontogenetic stages (stages of growth).

Co-author of the study, James Clark, (Ronald Weintraub Professor of Biology at the George Washington University’s Columbian College of Arts and Sciences), explained that by looking at how this dinosaur changed as it grew up, they could see that over time, individuals lost their sharp meat-eating teeth. By the time these dinosaurs had reached adolescence they were toothless and they did not grow another set as mature adults.

The Remarkable Ontogeny of Limusaurus

Picture credit: George Washington University

Indentifying Ontogenetically Variable Features in Limusaurus inextricabilis

Seventy-eight ontogenetically variable features were identified in the specimens. Palaeontologists are aware that many ornithischian dinosaurs such as ceratopsids (horned dinosaurs) and the duck-billed dinosaurs, change dramatically as they grow into adults, such dramatic changes in an animal’s appearance have not been extensively documented in the Theropoda. Despite the changes as Limusaurus grew up, the assessment of where this theropod is nested in the ceratosaurian family tree remains relatively unchanged.

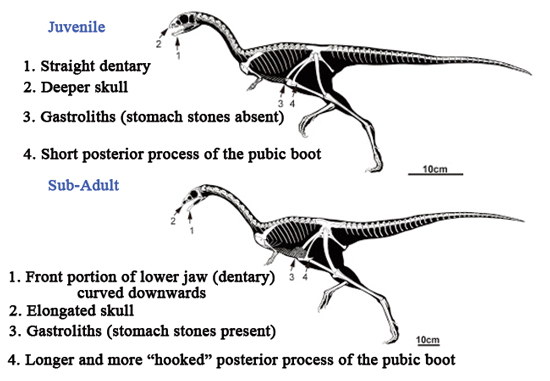

The Differences Between Individual Dinosaurs at Different Growth Stages

Picture credit: Journal of Current Biology

Key

(1) straight (juvenile) or ventrally deflected (sub-adult) anterior end of the dentary (downward pointing lower jaw).

(2) relatively deep (juvenile) or elongate (sub-adult) skull.

(3) gastroliths absent (juvenile) or present (sub-adult).

(4) short (juvenile) or elongate (sub-adult).

Commenting on the significance of their research, Dr James Clark, (George Washington University) explained:

“This discovery is important for two reasons. First, it’s very rare to find a growth series from baby to adult dinosaurs. Second, this unusually dramatic change in anatomy suggests there was a big shift in Limusaurus’ diet from adolescence to adulthood.”

A Carnivore and then Herbivore

The Limusaurus specimens that represented stage 1 (very youngest animals), had a total of forty-two teeth. Stage 2 had thirty-four, whilst in the most mature stages from stage 4 onwards, the specimens were toothless (edentulous). Gastroliths were found in association with larger individuals, and significantly, the size and number of the stones seemed to increase as the dinosaur matured. The presence of stomach stones indicates a herbivorous diet, a switch from meat-eating to plant-eating as the dinosaur grew up was also suggested by carbon and oxygen isotope analysis from bone samples.

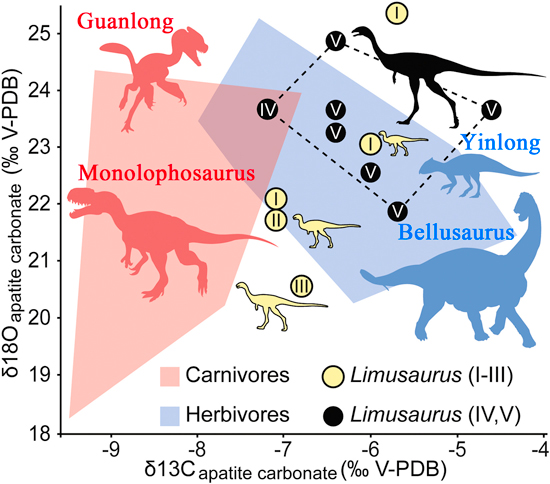

Carbon Isotope Composition of L. inextricabilis Compared to other Dinosaurs from the Upper Shishugou Formation

Picture credit: Current Biology

The diagram above shows the carbon/oxygen isotope analysis from the Limusaurus fossil material. Blue polygons show the ranges for herbivorous behaviour, whilst the red polygons show likely carnivorous feeding behaviour. The various Limusaurus ontogenetic ranges are plotted. Growth stages one to three indicate likely meat-eating habit in young and juvenile Limusaurus specimens, with a switch to a plant-eating diet (later stages). The data is plotted alongside meat-eating, plant-eating contemporaries of Limusaurus from the Upper Upper Shishugou Formation (Oxfordian faunal stage of the early Late Jurassic). The dashed lines represent the data related to sub-adult Limusaurus.

Close to the Bird Lineage

Limusaurus belongs to that part of the Theropoda that is believed to be closely allied to the evolutionary ancestors of the birds. Dr Clark et al in the formal description of this dinosaur in 2009, described the species’ hand development (manus) and noted that the reduced first digit might have been transitional towards the digit configuration of modern birds (digits II, III and IV). This new data could help scientists to understand how birds lost their teeth and the beak evolved.

To read an article on the naming and describing of Limusaurus: Chinese Ceratosaur and Dinosaur/Avian Links.

Everything Dinosaur Comments

Commenting on why these dinosaurs adapted to a different diet as they grew older, a spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur said:

“The adoption of a new feeding strategy as the animal matured might reflect a degree of opportunism by this species. Faced with an abundance of plant food within easy reach, it might have been advantageous for this dinosaur to feed on vegetation rather than expanding energy in the pursuit of prey. Perhaps, as the animal grew, plant food became an increasing proportion of its diet, this dinosaur transitioning from a carnivore/omnivore phase through to a stage where plant matter made up by the far the greatest proportion of its calorific intake.”

For theropod dinosaur figures and prehistoric animal models: Everything Dinosaur Prehistoric Animal Models.

The research was performed by Shuo Wang of the Capital Normal University and Mr. Stiegler under the guidance of Xu Xing of the Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, and Dr Clark. A National Science Foundation grant funded the research.

The scientific paper: “Extreme Ontogenetic Changes in a Ceratosaurian Theropod” published in the journal “Current Biology”.

Visit the website of Everything Dinosaur: Everything Dinosaur.