The Earliest Reptile Body Impressions with Scaly Skin are Described

Scientists have identified the oldest reptile skin impressions from a remarkable fossil discovered in Germany. The fossil also preserves possible evidence of a cloaca (vent). The vent shape and structure are reminiscent of the vents found in extant turtles and living squamates. Dr Lorenzo Marchetti from the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin led the research. The study has been published in the academic journal “Current Biology”.

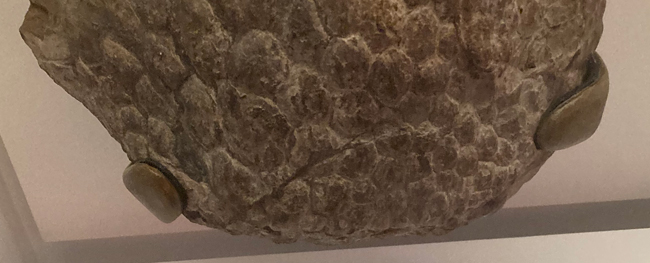

The earliest resting trace of a stem reptile and the fossil specimen preserves the earliest evidence of epidermal scales and a cloaca (vent). These scales are preserved on a newly described resting trace Cabarzichnus pulchrus representing the oldest and most complete body-impression occurrence of a Palaeozoic stem reptile. Picture credit: Lorenzo Marchetti

Picture credit: Lorenzo Marchetti

The Oldest Reptile Skin Impressions Known to Science

The stunning and beautifully preserved skin impressions were found on a slab with associated footprints of an early reptile (Varanopus microdactylus). The material is from the Goldlauter Formation and dates from the Early Permian. Modern radiometric dating of volcanic ash layers allows the finds to be precisely dated. They are around 299-298 million years old. This makes them the oldest direct evidence of reptile skin found to date.

Skin structures such as scales, feathers or horned beak remnants are documented by a large number of fossils. For example, several examples of dinosaur integument are known. Recently, we wrote a blog post about a remarkable study of the skin of Diplodocus. However, the German skin impressions are around twice as old as the Diplodocus skin impression material.

To read about the study of diplodocid integument: The Amazing Skin of a Young Diplodocus.

A sauropod skin impression (NHMUK R1868) on display as part of the London Natural History Museum Patagotitan exhibition. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Commenting on the significance of the research, Dr Lorenzo Marchetti stated:

“Such soft tissue structures are extremely rare in the fossil record – and the further back we go in geological history, the more extraordinary they become. The traces from the Thuringian Forest open up new perspectives on the early development of reptiles and their skin structures.”

Cabarzichnus pulchrus

The newly described resting traces have been named Cabarzichnus pulchrus. It is a new genus and species of trace fossil. The associated footprints have proportions similar to those of bolosaurs – an early group of reptiles from the lineage of today’s lizards. The preserved scale shapes range from diamond-shaped to hexagonal to laterally pointed and show remarkable parallels to integuments of living reptiles.

We Have a Cloaca

The skin impression representing the base of the tail preserves possible evidence of a cloaca (vent). Most terrestrial vertebrates have a cloaca – a common opening for the excretion of faeces and urine, which is also the exit point for the reproductive organs. Only live-bearing mammals have separate openings. In the fossil record, the cloaca is almost never preserved and clearly recognisable as part of the soft tissue. However, the skin impression shows traces of a cloaca opening near the base of the tail. The impression of the narrow slit suggests that the cloaca of the Cabarzichnus track maker differs in shape and orientation from that of dinosaurs and crocodiles, resembling instead the cloaca of turtles, lizards and snakes.

Trace fossils which preserve the oldest reptile skin impressions can provide a more complete picture of the evolution of early land vertebrates.

Dr Marchetti added:

“Trace fossils are much more than mere footprints. They preserve details of anatomy that would otherwise be completely lost and contribute significantly to a better understanding of the evolution of early terrestrial vertebrates.”

This record of dermal and epidermal scales provides evidence for the co-existence of epidermal and dermal scales in Carboniferous stem amniotes and for epidermal scale differentiation in Asselian stage (Early Permian) stem reptiles. Therefore, this adaptation precedes the main phases of the global warming and aridification associated with the Early Permian and probably enabled the diversification of stem reptiles.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “The earliest reptile body impressions with scaly skin” by Lorenzo Marchetti, Antoine Logghe, Michael Buchwitz, Mark J. MacDougall, Arnaud Rebillard, Thomas Martens and Jörg Fröbisch published in Current Biology.

For models and figures of Palaeozoic vertebrates: Models of Early Terrestrial Vertebrates.