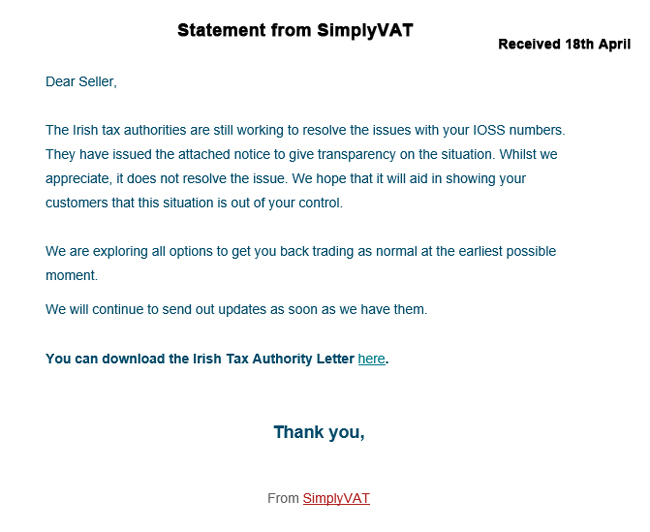

A scientific paper has just been published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE that describes a new species of giant ichthyosaur. This huge marine reptile, named Ichthyotitan severnensis could have been about as big as a blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). The discovery of the fragmentary remains of a second gigantic jawbone in Somerset supports the hypothesis that giant ichthyosaurs were present in the Late Triassic ecosystem.

A washed-up Ichthyotitan severnensis carcase on the beach being visited by two hungry theropod dinosaurs and a flock of curious pterosaurs. Picture credit: Sergey Krasovskiy.

Giant Ichthyosaurs from Somerset

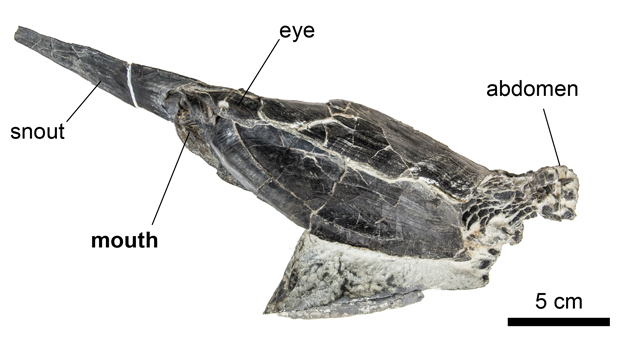

Fossil collector and co-author of this study Paul de la Salle, found a portion of fossil jaw in May 2016. He later returned to the location (the beach at Lilstock, west Somerset) and found more pieces that together formed a partial surangular more than a metre in length. The second fragmentary jawbone, also a surangular was found on a beach a few miles to the east of the original fossil discovery.

In May 2020, Father and daughter, Justin and Ruby Reynolds from Braunton, Devon found the first pieces of the second surangular. They were fossil hunting on the beach at Blue Anchor. Ruby, then aged eleven found the first chunk of fossil bone and went onto to find several more fragments.

Realising that Ruby may have discovered something of considerable scientific value, the family contacted leading ichthyosaur expert, Dr Dean Lomax, a palaeontologist at The University of Manchester. Dr Lomax, who is also a 1851 Research Fellow at the University of Bristol, contacted Paul de la Salle as he recognised the striking similarity between the two fossil finds.

Dr Dean Lomax commented:

“I was amazed by the find. In 2018, my team (including Paul de la Salle) studied and described Paul’s giant jawbone and we had hoped that one day another would come to light. This new specimen is more complete, better preserved, and shows that we now have two of these giant bones – called a surangular – that have a unique shape and structure. I became very excited, to say the least.”

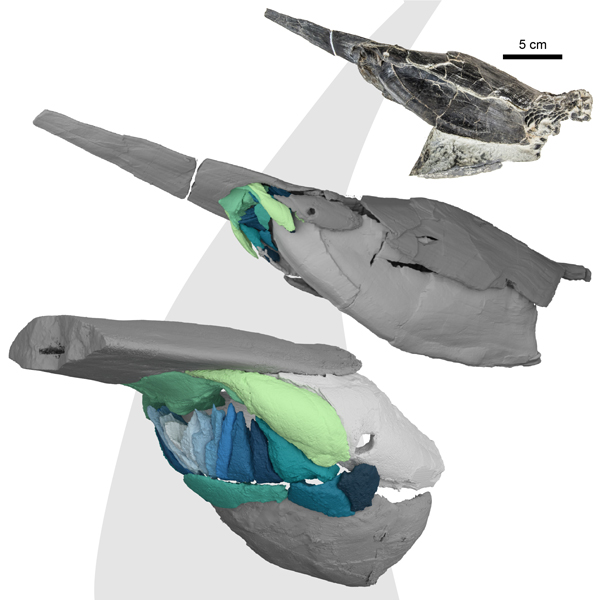

Photograph of the nearly complete giant jawbone (surangular), along with a comparison with the 2018 bone (middle and bottom) found by Paul de la Salle. Picture credit: Dr Dean Lomax.

Hunting for More Fossil Evidence

Justin and Ruby, together with Paul, Dr Lomax, and several family members, visited the site to hunt for more pieces of fossil bone. Over time, the team found additional fragments of the same jaw which fit together perfectly, like a multimillion-year-old ichthyosaur jigsaw.

Father Justin explained:

“When Ruby and I found the first two pieces we were very excited as we realised that this was something important and unusual. When I found the back part of the jaw, I was thrilled because that is one of the defining parts of Paul’s earlier discovery.”

The last piece of bone was recovered in October 2022.

Part of the research team in 2020 examining the initial finds (at the back) of the new discovery made by Ruby and Justin Reynolds. Additional sections of the bone were subsequently discovered. From left to right, Dr Dean Lomax, Ruby Reynolds, Justin Reynolds and Paul de la Salle. Picture credit: Dr Dean Lomax.

Ichthyotitan severnensis

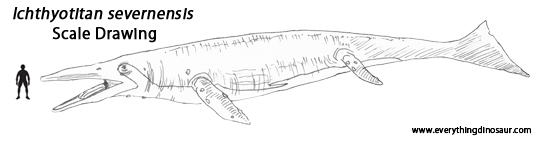

Lead author of the study, Dr Lomax commented that the jaw fossils belong to a new species of enormous ichthyosaur. It would have measured perhaps as much as twenty-five metres in length. Ichthyotitan severnensis was probably larger than any extant toothed whale. Based on comparisons with better known shastasaurid ichthyosaurs, it could have been as big as a blue whale. Analysis of the geology of the two fossil sites along with a detailed comparison of the two surangular fossils supports the team’s hypothesis that these fossils represent an enormous ichthyosaur that is new to science.

An Ichthyotitan severnensis scale drawing. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The genus and species name translates as “giant fish lizard of the Severn”.

The fossil material is estimated to be around 202 million years old, dating to the end of the Triassic (Rhaetian faunal stage). Gigantic ichthyosaurs (Shastasauridae) swam in the seas while the Dinosauria were beginning to dominate terrestrial environments. Ichthyotitan was one of the last of the shastasaurids, these Somerset fossils represent the last of their kind. The Shastasauridae family are thought to have become extinct at the end of the Triassic.

Ichthyotitan severnensis was not the world’s first giant marine reptile, but de la Salles’ and Reynolds’ discoveries are unique among those known to science. These two bones appear to be approximately thirteen million years younger than their latest geologic relatives, including Shonisaurus sikanniensis (British Columbia, Canada), and Himalayasaurus tibetensis from Tibet, China.

Dr Lomax added:

“I was highly impressed that Ruby and Justin correctly identified the discovery as another enormous jawbone from an ichthyosaur. They recognised that it matched the one we described in 2018. I asked them whether they would like to join my team to study and describe this fossil, including naming it. They jumped at the chance. For Ruby, especially, she is now a published scientist who not only found but also helped to name a type of gigantic prehistoric reptile. There are probably not many 15-year-olds who can say that! A Mary Anning in the making, perhaps.”

Ruby exclaimed:

“It was so cool to discover part of this gigantic ichthyosaur. I am very proud to have played a part in a scientific discovery like this.”

A giant pair of swimming Ichthyotitan severnensis. Picture credit: Gabriel Ugueto.

Not Yet Fully Grown

Further examinations of the bones’ internal structures have been carried out by master’s student, Marcello Perillo, from the University of Bonn, Germany. His research confirmed the ichthyosaur origin of the bones and also revealed that the animal was still growing at the time of death.

He said:

“We could confirm the unique set of histological characters typical of giant ichthyosaur lower jaws: the anomalous periosteal growth of these bones hints at yet to be understood bone developmental strategies, now lost in the deep time, that likely allowed Late Triassic ichthyosaurs to reach the known biological limits of vertebrates in terms of size. So much about these giants is still shrouded by mystery, but one fossil at a time we will be able to unravel their secret.”

Concluding the work, Paul de la Salle added:

“To think that my discovery in 2016 would spark so much interest in these enormous creatures fills me with joy. When I found the first jawbone, I knew it was something special. To have a second that confirms our findings is incredible. I am overjoyed.”

Ichthyotitan severnensis Fossils on Public Display

The fossilised remains will soon be put on display at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery (Bristol).

Dr Lomax summarised the study:

“This research has been ongoing for almost eight years. It is quite remarkable to think that gigantic, blue whale-sized ichthyosaurs were swimming in the oceans around what was the UK during the Triassic Period. These jawbones provide tantalising evidence that perhaps one day a complete skull or skeleton of one of these giants might be found. You never know.”

To read Everything Dinosaur’s 2018 article about the first surangular fossil discovery: Late Triassic Giant Ichthyosaurs.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Manchester in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper “The last giants: New evidence for giant Late Triassic (Rhaetian) ichthyosaurs from the UK” by Lomax D. R., de la Salle, P., Perillo, M., Reynolds, J., Reynolds, R. and Waldron, J. F. published in PLOS ONE.

Visit the website of Dr Dean Lomax: British Palaeontologist Dr Dean Lomax.