Thalassotitan – Terror of the Seas

An international team of researchers have uncovered the remains of a huge mosasaur, one that was adapted to hypercarnivory and was an apex predator in the shallow seas of North Africa around 66 million years ago. In addition, the scientists have unearthed remains of other marine vertebrates that shared this giant’s habitat. Acid damage on the bones suggest that these animals were prey and ingested by mosasaurids potentially this new leviathan named Thalassotitan atrox.

Thalassotitan atrox

Late Cretaceous Marine Giant

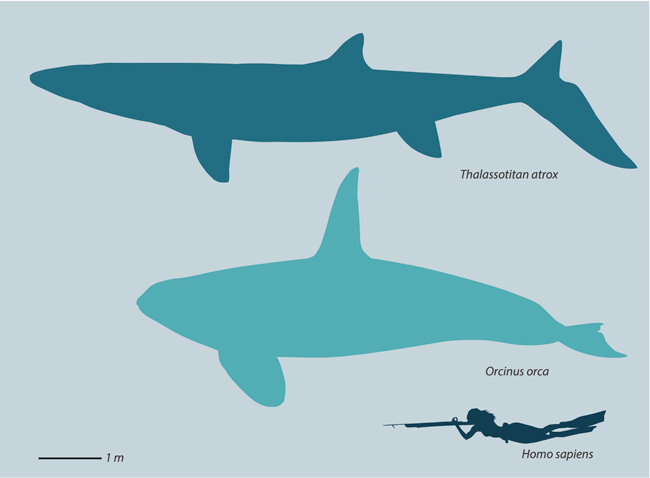

The remains of this Late Cretaceous marine giant, including a 1.4-metre-long-skull were excavated from the Upper Cretaceous, phosphatic beds of the Ouled Abdoun Basin (northern Morocco). High sea levels created a shallow, tropical sea that teemed with life in North Africa and at the very end of the Cretaceous, approximately 66 million years ago (Maastrichtian faunal stage of the Cretaceous), the 9-metre-long Thalassotitan was the apex marine predator.

A Contemporary of Tyrannosaurus rex

Thalassotitan atrox was a mosasaur, which are extinct members of the largest order of reptiles the Squamata. As such, Thalassotitan was more closely related to snakes and lizards than it was to archosaurs such as crocodilians and the Dinosauria. However, it was a contemporary of Tyrannosaurus rex and like T. rex it was a hypercarnivore, attacking and feeding upon other large vertebrates.

An Apex Predator

The massive jaws and robust, conical teeth suggest that Thalassotitan was an apex predator, filling a similar environmental nice as Orcas (Orcinus orca) and the Great White shark (Carcharodon carcharias) in extant marine ecosystems. The research team, who included Dr Nick Longrich, Senior Lecturer from the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath and lead author on the study, published in the journal Cretaceous Research, postulate that the acid-etched fossilised bones of other vertebrates found in the same deposit might represent prey ingested by mosasaurids, likely Thalassotitan.

Thalassotitan’s large teeth are often broken and show extensive signs of wear, with some teeth in the jaws worn down to the root. Piscivory (fish-eating) would not have caused this damage, the scientists conclude that this is evidence to support the theory that Thalassotitan was an apex predator.

Dr Longrich commented:

“Thalassotitan was an amazing, terrifying animal. Imagine a Komodo Dragon crossed with a great white shark crossed with a T. rex crossed with a killer whale.”

Thalassotitan’s Potential Victims

The scientists comment that possible remains of Thalassotitan’s victims may have been found. Fossils from the same beds show damage from acid, perhaps evidence of their partial digestion in the stomach of Thalassotitan before the bones and teeth were regurgitated. Fossils with this particular damage include large predatory fish, a sea turtle, a half-metre-long elasmosaurid (plesiosaur) skull, and jaws and skulls of at least three different mosasaur species.

Dr Longrich explained the significance of the acid etched fossil bones and teeth stating:

“It’s circumstantial evidence. We can’t say for certain which species of animal ate all these other mosasaurs. But we have the bones of marine reptiles killed and eaten by a large predator and in the same location, we find Thalassotitan, a species that fits the profile of the killer – it’s a mosasaur specialised to prey on other marine reptiles. That’s probably not a coincidence.”

Mosasaurids Not in Decline Immediately Prior to their Extinction

The discovery of T. atrox along with the other dozen or so mosasaurid genera identified from fossils found in the Ouled Abdoun Basin suggests that mosasaurs continued to diversify and fill new niches until their extinction at the end of the Cretaceous. These marine lizards probably filled ecological niches vacated by the recently extinct ichthyosaurs and they may have out-competed plesiosaurs. The mosasaurs were probably not in decline prior to the end-Cretaceous extinction event.

Co-author of the scientific paper, Professor Nour-Eddine Jalil (Muséum National D’Histoire Naturelle, Paris), added:

“The phosphate fossils of Morocco offer an unparalleled window on the paleobiodiversity at the end of Cretaceous. They tell us how life was rich and diversified just before the end of the ‘dinosaur era’, where animals had to specialise to have a place in their ecosystems. Thalassotitan completes the picture by taking on the role of the megapredator at the top of the food chain.”

A Threat to Other Marine Animals and to Other Thalassotitans

Extensive pathology associated with the fossilised remains of Thalassotitan indicate that these large mosasaurs sustained injuries as a result of combat. Injuries not only sustained through predation but also during intra-specific combat – fights with members of their own species. The skull and jaws show signs of injury. Other mosasaur fossils have similar pathology, but in Thalassotitan these wounds were exceptionally common, suggesting frequent, intense fights over feeding grounds or mates.

Merciless Sea Monster

Although not the largest mosasaurid described to date, specimens from the Tylosaurus and Hainosaurus genera indicate body lengths in excess of twelve metres, Thalassotitan was a formidable predator, and this is emphasised by the binomial scientific name chosen by the research team. The genus name is from the Greek for “sea monster” or “sea titan” and the species name means “cruel or merciless”

Phylogenetic analysis recovers Thalassotitan as a close relative of Prognathodon currii and P. saturator within the Mosasauridae tribe the Prognathodontini. Prognathodon is represented by numerous species all known from the end of the Cretaceous (Campanian to Maastrichtian faunal stages). Prognathodon species are characterised by very robust skulls, with powerful jaws.

More Discoveries Waiting to be Made

Dr Longrich and his colleagues stressed the importance of the prehistoric animal fossils from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco and hinted that further exciting discoveries are likely to be made.

He stated:

“There’s so much more to be done. Morocco has one of the richest and most diverse marine faunas known from the Cretaceous. We’re just getting started understanding the diversity and the biology of the mosasaurs.”

The extensive, Upper Cretaceous phosphate beds of the Ouled Abdoun Basin have proved palaeontologists with more than a dozen species of mosasaurid to study. Many of these mosasaurs show anatomical adaptations that permitted them to exploit different niches in the ecosystem (niche partitioning). For example, Gavialimimus (G. almaghribensis) had a long, narrow jaw lined with interlocking teeth suggesting that this mosasaur specialised in hunting small fish. In contrast the recently described Pluridens serpentis had disproportionately small eyes, suggesting that this mosasaurid either hunted at depth or within murky water.

To read Everything Dinosaur’s article about P. serpentis: Giant Moroccan Mosasaurid Pluridens serpentis.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bath in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Thalassotitan atrox, a giant predatory mosasaurid (Squamata) from the Upper Maastrichtian Phosphates of Morocco” by Nicholas R. Longrich, Nour-Eddine Jalil, Fatima Khaldoune, Oussama Khadiri Yazami, Xabier Pereda-Suberbiola, and Nathalie Bardet published in Cretaceous Research.

For models and replicas of mosasaurs and other marine reptiles: CollectA Scale Prehistoric Animal Models.