The De-extinction of the Thylacine

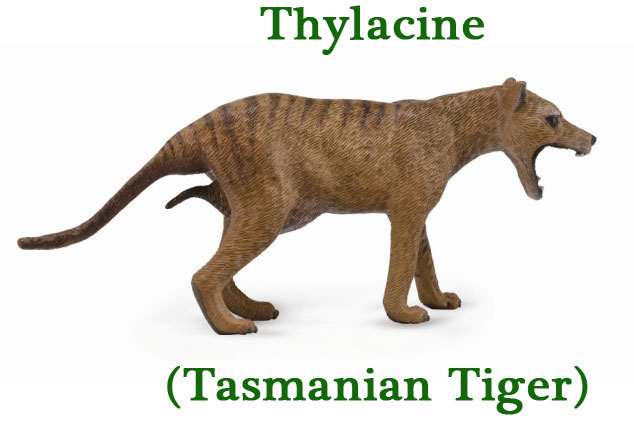

On the 7th of September, 1936 the last known Thylacine died at Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart (Tasmania). Although most of the scientific community believe that the Thylacine, or as it is sometimes called the Tasmanian Tiger, is extinct there are occasional reports of sightings, either from Tasmania or elsewhere in Australia.

Researchers at the University of Melbourne believe that extinction does not have to mean forever, and they are pursuing a Thylacine de-extinction project to bring back one of the last of Australia’s marsupial apex predators.

The research team led by Professor Andrew Pask of the Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research (TIGRR) Lab is confident that a newly signed partnership agreement with Dallas-based Colossal Biosciences will bring the resurrection of the Tasmanian Tiger one step closer.

Conserving Australia’s Wildlife Heritage

The new American/Australian partnership will provide access to CRISPR DNA editing technology and allow scientists to pool their resources in their quest to bring back the Thylacine and to prevent many of Australian’s endangered mammals from going the same way.

Commenting on the significance of the new partnership and the access to state-of-the-art gene editing technology, Professor Pask stated:

“We can now take the giant leaps to conserve Australia’s threatened marsupials and take on the grand challenge of de-extincting animals we had lost.”

The Professor added:

“A lot of the challenges with our efforts can be overcome by an army of scientists working on the same problems simultaneously, conducting and collaborating on the many experiments to accelerate discoveries. With this partnership, we will now have the army we need to make this happen.”

Genome Sequenced

Thylacines (family Thylacinidae) are part of the marsupial order Dasyuromorphia. In 2018, researchers led by Professor Pask sequenced the genome of the Thylacine. This was achieved by extracting DNA samples from the pouch of a young Thylacine preserved in a jar of alcohol (specimen number C5757), part of the marsupial collection at Melbourne Museum. The team were able to read the approximately 3 billion nucleotide “letters” of the Thylacine genome and with the help of powerful computers to sequence them.

Armed with this knowledge, the research team could establish the genetic relationship between the extinct Thylacine and living, closely related members of the Dasyuromorphia such as the Tasmanian devil.

It would be theoretically possible to mimic the Thylacine genome and reconstruct it using marsupial stem cells.

A Focus on Protecting Extant Marsupials

Professor Pask explained that TIGGR will concentrate efforts on establishing the reproductive technologies tailored to Australian marsupials, such as IVF and gestation without a surrogate, as Colossal simultaneously deploy their CRISPR gene editing and computational biology capabilities to reproduce Thylacine DNA. This research will also help in the long-term protection of many of Australia’s indigenous marsupials, study of Thylacine DNA will help scientists to better understand the genetic makeup of closely related, extant genera. This research will influence the next generation of Australia’s marsupial conservation efforts.

This partnership with Colossal follows a significant philanthropic donation of $5 million AUD for the TIGGR Lab earlier this year.

Sharing Expertise

Colossal’s experience in CRISPR gene editing will be partnered with TIGGR’s work sequencing the Thylacine genome and identifying marsupials with similar DNA to provide living cells and a template genome that can then be edited to recreate the genetic instructions required to resurrect the extinct marsupial.

Professor Park added:

“The question everyone asks is ‘how long until we see a living Thylacine’ – and I’ve previously believed in ten years’ time we would have an edited cell that we could then consider progressing into making into an animal. With this partnership, I now believe that in ten years’ time we could have our first living baby Thylacine since they were hunted to extinction close to a century ago.”

The TIGRR Lab is believed to be close to producing the first laboratory-created embryos from Australian marsupial sperm and eggs.

Marsupials have a much shorter gestation period when compared to placental mammals. It is conceivable to produce a marsupial without the aid of a surrogate mother. Growing a marsupial, even a Thylacine in a test-tube from conception to the stage at which it would have been born.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Melbourne in the compilation of this article.