A Small Azhdarchoid Pterosaur from Late Cretaceous British Columbia

As the Cretaceous progressed, so the once diverse and dominant Pterosauria began to be replaced by the rapidly evolving and radiating Aves (birds). When it came to aeronautics, feathers were better than flaps of skin. The last of the flying reptiles, those that survived into the very Late Cretaceous were giants, huge animals some as tall as a giraffe, even the smallest of these pterosaurs, creatures like Montanazhdarcho minor and Eurazhdarcho langendorfensis had wingspans comparable to the largest volant birds today. It seemed that the last of the pterosaurs, most of which belong to a single family, the Azhdarchidae, were all big.

British Columbia Pterosaur Flies Against Conventional Thinking

Picture credit: Mark Witton

Studying Pterosaurs

The consensus went something like this, smaller pterosaurs were gradually out competed by and replaced by birds. However, a newly described pterosaur fossil from British Columbia, the first of its kind from western North America has challenged this thinking. It seems that smaller pterosaurs did survive into the Late Cretaceous and their lack of presence in the fossil record probably has more to do with preservation basis than with an inability to compete with birds.

The fossilised remains of a small-bodied pterosaur, an animal that probably had a wingspan of around 1.5 metres, that’s roughly the size of an adult European Herring Gull wingspan (Larus argentatus), were found on Hornby Island, a small body of land on the east coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia back in 2009. The fragmentary fossils, were located in carbonate nodules and date from approximately 77 million years ago (Campanian faunal stage of the Cretaceous), the finder, a volunteer with the Royal British Columbia Museum, donated the specimen to the Museum.

For models and replicas of pterosaurs and other prehistoric animals: CollectA Deluxe Scale Models and Figures.

Studying a Pterosaur Fossil Specimen

At the time, the fossil material was given to Victoria Arbour, a then PhD student and dinosaur expert at the University of Alberta. Victoria, as a postdoctoral researcher at North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, then contacted Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone, a palaeobiology PhD student (University of Southampton) and the Royal British Columbia Museum sent the specimen for analysis in collaboration with Dr Mark Witton, a pterosaur expert at the University of Portsmouth.

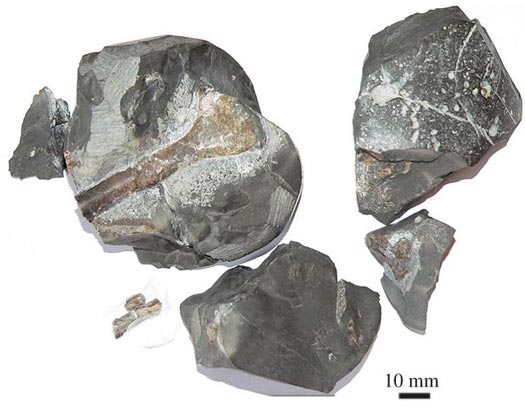

The Pterosaur Fossilised Bones can be Identified in the Carbonate Nodules

Picture credit: Sandy McLachlan

Adding to our Knowledge Base About Late Cretaceous Pterosaurs

The fossils comprising a partial humerus (upper arm bone), vertebrae and other bone fragments show characteristics that led them to be classified as azhdarchoid pterosaur material. Previous studies suggest that the Late Cretaceous skies were only occupied by much larger pterosaur species and birds, but this new finding, which is reported in the Royal Society journal “Open Science”, provides crucial information about the diversity and success of Late Cretaceous pterosaurs.

Lead author, PhD student Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone, explained the significance of this British Columbian discovery:

“This new pterosaur is exciting because it suggests that small pterosaurs were present all the way until the end of the Cretaceous, and weren’t out competed by birds. The hollow bones of pterosaurs are notoriously poorly preserved, and larger animals seem to be preferentially preserved in similarly aged Late Cretaceous ecosystems of North America. This suggests that a small pterosaur would very rarely be preserved, but not necessarily that they didn’t exist.”

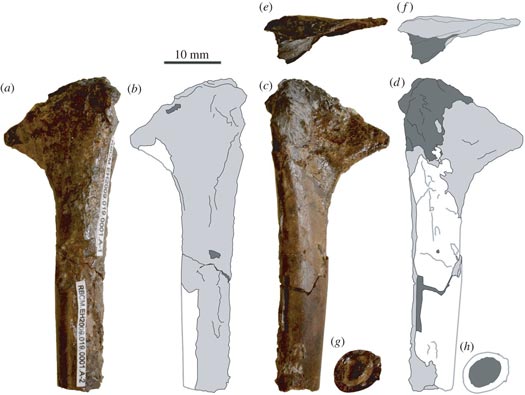

Photographs and Line Drawings of the Azhdarchoid Humerus

Picture credit: Royal Society Open Science

An Azhdarchoid Humerus

The picture above shows photographs and interpretative line drawings of the fossilised left humerus (a, b) dorsal view, (c, d) ventral view, (e, f) proximal and (g, h) distal view. The shading denotes preserved bone cortex (white), weathered bone (light grey) and matrix infill (dark grey). The scale bar in the picture equals ten millimetres, indicating a cat-sized Pterosaur.

Late Cretaceous Pterosaur No Bigger Than a Domestic Cat

Picture credit: Mark Witton

Dr Witton commented:

“The specimen is far from the prettiest or most complete pterosaur fossil you’ll ever see, but it’s still an exciting and significant find. It’s rare to find pterosaur fossils at all because their skeletons were lightweight and easily damaged once they died, and the small ones are the rarest of all. But luck was on our side and several bones of this animal survived the preservation process.

Happily, enough of the specimen was recovered to determine the approximate age of the pterosaur at the time of its death. By examining its internal bone structure and the fusion of its vertebrae we could see that, despite its small size, the animal was almost fully grown. The specimen thus seems to be a genuinely small species, and not just a baby or juvenile of a larger pterosaur type.”

Small Pterosaurs in the Late Cretaceous

Although the scientists cannot be sure what this pterosaur actually looked like, it has been given the typical skull and toothless beak of an azhdarchid, although in reality little can be deduced from the fragmentary fossil as to the appearance of this Late Cretaceous flying reptile. However, the British Columbian fossil discovery is extremely important, as Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone added:

“The absence of small juveniles of large species – which must have existed – in the fossil record is evidence of a preservational bias against small pterosaurs in the Late Cretaceous. It adds to a growing set of evidence that the Late Cretaceous period was not dominated by large or giant species, and that smaller pterosaurs may have been well represented in this time. As with other evidence of smaller pterosaurs, the fossil specimen is fragmentary and poorly preserved: researchers should check collections more carefully for misidentified or ignored pterosaur material, which may enhance our picture of pterosaur diversity and disparity at this time.”

The study, which also involved researchers from the University of Portsmouth, North Carolina State University, and the University of Alberta, was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Dr Mark Witton, as well has having a remarkable knowledge of the Pterosauria and fantastic drawing skills, has authored a number of books on the subject of flying reptiles. In 2013, his marvellous book “Pterosaurs, Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy” was published by Princeton University Press. We at Everything Dinosaur recommend this book, not only for those with an academic interest but also for the general reader.

To read a review of “Pterosaurs” by Dr Mark Witton: “Pterosaurs” – A Book Review.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the help and support of the University of Southampton in the compilation of this article.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment