Thirsty Woolly Mammoths of St. Paul Island Identified in New Study

St. Paul’s and Wrangel Island Woolly Mammoth Populations

This week has seen the publication of research undertaken by an international team of scientists led by academics from the University of Pennsylvania, that explains the demise of one of the last populations of Woolly Mammoths to have lived on Earth.

Mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) survived on the remote Alaskan island of St. Paul until around 5,600 years ago (+/- 100 years or so), whilst their mainland cousins were extinct by about 10,500 years ago. Writing in the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences” (United States), the researchers conclude that a warming climate which led to rising sea levels caused the amount of freshwater available to fall dramatically, in essence the Woolly Mammoths died of thirst.

Study Suggests Some of the Last of the Woolly Mammoths were Unable to Quench Their Thirst

Lack of freshwater is suspected to have led to the demise of the Woolly Mammoth population on St. Paul Island.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture (above) was created using Papo Woolly Mammoth models.

To view the Papo “Les Dinosaures” range: Papo Prehistoric Animal Models and Figures.

The Island of St. Paul in Relation to Wrangel Island

Readers of this blog will probably know that the very last population of Woolly Mammoths to have existed, survived on Wrangel Island until about 4,300 years ago (although an extinction date of as recently as about 1,700 B.C. has been proposed).

Both St. Paul Island and Wrangel are remote locations deep within the Arctic circle, however, there are considerable differences between these two islands and whilst scientists such as Professor Russell Graham (University of Pennsylvania) and lead author of the St. Paul Island study, propose that a lack of drinking water led to the St. Paul’s Island Mammoth population dying out, debate remains as to the probable cause of the Wrangel Island extinction.

In both cases the presence of humans impacting on the population of Mammoths can be ruled out, these hairy elephants were long gone before the first humans visited these isolated, desolate places (once sea levels rose).

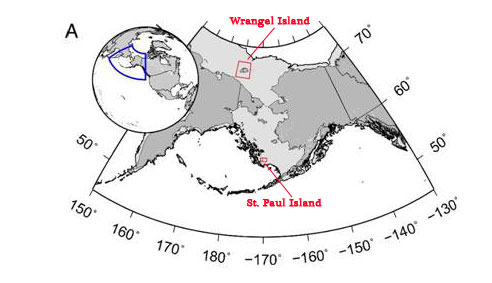

The Location of St. Paul Island in Relation to Wrangel Island

The dark grey areas represent today’s landmass, the light grey areas show the extent of the Bering Land Bridge (Beringia).

Picture credit: PNAS with additional annotation by Everything Dinosaur

St Paul Island and Wrangel Island

The picture above shows the approximate position of the Bering Land Bridge (Beringia) in light grey compared to the landmasses of Siberia and Alaska today (dark grey). At its maximum during the Quaternary glacial intervals, the land joining Asia to North America would have been over six hundred miles wide, over the last 20,000 years rising sea levels led to the eventual loss of a land link between the continents of North America and Asia.

St. Paul Island was part of the southern portion of Beringia. Today, it is located in the Bering Sea. In contrast, the much larger Wrangel Island is found in what was the northern portion of Beringia and it is located today in the Arctic Ocean.

Wrangel Island is over seventy times bigger than St. Paul Island, in the past both these islands were considerably bigger but with a warming climate in the latter stages of the Pleistocene and into the Holocene Epoch, sea levels rose and St. Paul Island in particular began to shrink. The island is presently, around forty square miles in size, the researchers used a variety of techniques to plot the ingress of sea water and the decline of freshwater on the island over the last fifteen thousand years.

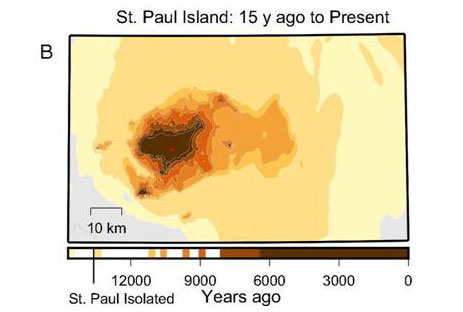

The Reduction of St. Paul Island from the Late Pleistocene to the Present Day

Picture credit: PNAS

Shrinking Islands

The picture above shows a palaeogeographical map compiled by the research team that plots the reduction in the size of St. Paul Island over the last 15,000 years or so. The red dot in the centre of the island (present size is outlined in brown), represents Lake Hill, a small, freshwater lake from which a series of sediment cores were extracted so that the scientists could trace the history of the location and how changes in climate affected the fauna and flora of the island.

The sediment cores (taken in 2013), built on data generated from core samples taken back in the 1960s and they have provided a number of independent indicators to suggest that the Mammoth population survived until around 5,600 years ago.

The flora of St. Paul Island remained relatively unchanged, however, the scientists were able to deduce that St. Paul Island shrank rapidly due to rising sea levels until about 9,000 years ago. It continued to shrink, albeit more slowly until around 6,000 years ago but declining freshwater sources and a generally drier climate with reduced precipitation from around 7,850 years ago to the time of the Mammoth’s extinction was probably the cause of the demise of this elephant population.

Independent Indicators of Mammoth Extinction

- Analysis of sedimentary ancient DNA (sedaDNA) to provide an understanding of the ancient flora of the environment and how a drying climate and rising sea levels impacted upon it.

- The level of fungal spores that are associated with animal dung (coprophilous fungal spore types). Three types of fungal spore were studied, this fungi would have thrived on Mammoth dung, the sudden elimination of the fungal spores from the core samples indicate a mega fauna extinction.

- Micro fossils such as those of water fleas (indicating freshwater) and pollen grains along with diatoms (different types of algae some of which are associated with sea water).

- Magnetic susceptibility, in arbitrary units (AU) of Lake Hill sediments from the cores, this data looks at the differences between different types of sediment and from this an understanding of changes in the palaeoenvironment over time can be mapped.

- Radiocarbon dating, isotope degradation analysis and analysis of protein remnants from St. Paul Island Mammoth remains.

Given the variety of information sources, the “best fit” for the Mammoth extinction is approximately 5,600 years ago (+/- 100 years).

The Mammoths Contributed to Their Own Downfall

As sources of freshwater dwindled, so the Mammoths would have congregated around the remaining waterholes. More intensive, localised Woolly Mammoth activity would have accelerated the fall in water levels. Vegetation would have been consumed therefore exposing sediments that would have been washed into the lakes and ponds thus degrading the water quality, reducing water levels further and exacerbating the already acute water shortage.

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“Extant Indian elephants can consume as much as two hundred litres a day, sometimes more if it is a lactating female. We suspect Mammoths too, had a high demand for drinking water. A concentration of mega fauna around remaining sources of drinking water on St. Paul Island would have probably accelerated the extinction. It is also likely, that with large animals having to survive on an ever diminishing landmass, the elephant population was already probably under considerable environmental stress.”

Lead author of the PNAS paper, Professor Russell Graham explained a likely extinction scenario:

“They [the Mammoths] were milling around, which would destroy the vegetation, we see this with modern elephants. This allows for the erosion of sediments to go into the lake, which is creating less and less fresh water. The Mammoths were contributing to their own demise.”

The scientific paper: “Timing and causes of mid-Holocene Mammoth extinction on St. Paul Island, Alaska”.