The Origin of High Frequency Hearing In Whales

Ancient “Echo Hunter” Provides Insight into Whale Evolution

Scientists from the College of Osteopathic Medicine, New York Institute of Technology (New York), in collaboration with colleagues from a number of other institutions including the Museum of Natural History (Paris), have published a paper on a newly described species of toothed whale, one that suggests that echolocation abilities started early in the cetaceans.

Ancient Toothed Whale Skull

Writing in the journal “Current Biology” the researchers report that they have found evidence of ultrasonic hearing and the use of echolocation as a probable navigation aid in the beautifully preserved inner ear of a 27-million-year-old toothed whale.

An Illustration of Echovenator (E. sandersi) A Newly Described Genus of Toothed Whale

Picture credit: A. Gennari

Known from a skull, jaws and an atlas bone (bone from the neck), which are believed to represent a single individual, Echovenator sandersi had features in its inner ear that suggest that this marine mammal could hear a greater range of high-pitched sounds when compared to most other mammals. Believed to be a basal member of the Odontocetes (toothed whales), this fossil suggests that sophisticated echolocation evolved very early on in this whale lineage.

From a Ditch in South Carolina

The fossil remains were discovered during work on a drainage ditch in Berkeley County, South Carolina fifteen years ago. The bones and fossil teeth are associated with a basal bed of the Chandler Bridge Formation (Upper Oligocene). The rocks of this formation were laid down in a marine environment, close to the shore (nearshore marine or possibly an embayment).

Commenting on the conclusions of the research, lead author Morgan Churchill (New York Institute of Technology), stated:

“We can tell a lot about how well this animal fits within whale evolution based on the cranial features and we can use that cranial anatomy to determine whether or not it could echolcate.”

Dr Churchill, a postdoctoral Fellow at the College of Osteopathic Medicine added:

“The fossil specimen shows several features that we would see in a modern whale with echolocation.”

The Prepared Fossil Skull of the Early Toothed Whale (E. sandersi)

Picture credit: M. Churchill/Journal of Current Biology

A Well-travelled Whale

In order to assess the morphology and likely capabilities of the inner ear of this early whale, a number of X-ray scans were taken of the skull fossils. The skull was carefully X-rayed at the Nikon Metrology X-ray facilities in Tring, (Buckinghamshire, England) and these results were compared to X-ray studies of living and extinct whales skulls undertaken at the University of Texas Austin and the National Museum of Natural History in Paris

By examining Echo Hunter’s inner ear, the researchers found evidence of its ability to receive ultrasonic frequencies. A soft tissue structure called the basilar membrane, while not present in the fossil itself, was indicated by other parts of the ear to be of a size and thickness consistent with high-frequency hearing.

Another part of the inner ear, a thin, bony structure within the cochlea, provided further evidence of a likely echolocation ability. Echolocation is the use of vocalisations to navigate and to find prey underwater, other studies have proposed that the ability to produce very high frequency sounds occurred early on in the evolution of the Cetacea, this new research suggests echolocation evolved in basal members of the toothed whale group.

Jonathan Geisler, a co-author of the study and a professor at the New York Institute of Technology commented:

“We had suspicions that they were echolocating but to really get down to a rough estimate of frequency, you really had to look in the inner ear in more detail and that’s where this project comes in.”

Echovenator sandersi

About the size of a small dolphin, Echovenator hunted fish and other small, nektonic creatures close to the shore. It used its echolocation to help it forage in the murky, sediment-filled coastal waters. The genus name is Latin which means “echo hunter”, the species name honours Albert Sanders, a former curator of The Charleston Museum, in recognition of his contribution to the scientific study of Cenozoic whales.

Mark D. Uhen, a professor at George Mason University, who in 2008 erected a new family of ancient whales, the Xenorophidae, the oldest and most primitive of the toothed whales, the whale family to which Echovenator has been ascribed, explained that previous research had suggested that the earliest toothed whales could echolocate, but that the new paper provided a clearer picture.

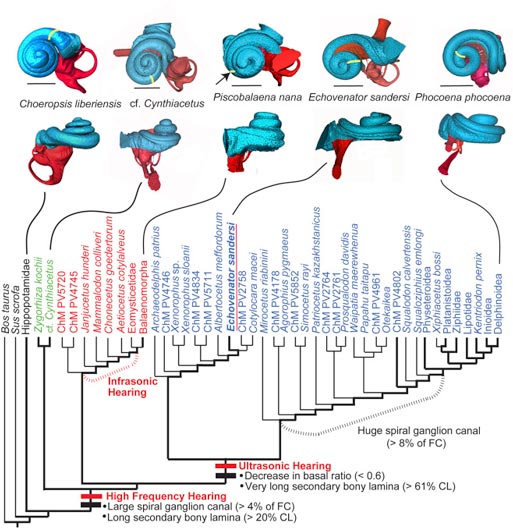

The Evolution of High Frequency Hearing and Echolocation in Whales

Picture credit: College of Charleston

The Evolution of Echolocation

Dr Uhen, who was not involved in this study, said that the development of high-frequency hearing in whales was a nice illustration of natural selection.

Professor Uhen commented:

“I think the way evolution mostly works is that animals adopt a behaviour, and then natural selection changes generation after generation so that they get better and better and better at that behaviour. Whales started feeding in the water so their feeding apparatus and their ears changed early.”

Heard the one about the origins of echolocation?: The Origins of Echolocation in Dolphins (related article).

To read an article about a potential terrestrial ancestor of whales: Deer-like Fossil Confuses Early Cetacean Evolution.

To read an article about a huge, Pliocene toothed whale that swam in the waters around Australia: Giant Aussie Whale a Terror of the Pliocene Seas.