CT Scan of Ancient Whale Reveals Evolution of Echolocation

There are many different types of dolphins, porpoises and toothed whales around today. These sleek, marine mammals are characterised by their superb adaptations to their environment, social behaviours, their intelligence and also their ability to use a complex sensory system to make sense of their underwater world.

Echolocation in Whales

Modern toothed whales (Odontocetes), use sonar frequencies (echolocation) to communicate with each other, for navigation and to locate and capture prey. These are the only marine mammals to have evolved the ability to hear and make sense of such high frequency sounds. But how did this super sensitive system evolve? This is a question that we are part way to solving thanks to a remarkable piece of research carried out by scientists at Monash University and Museum Victoria (Australia).

An Illustration of a Prehistoric Whale – Dorudon

Picture credit: Julius Csotonyi.

CT Scan of Ancient Whale Inner Ear Bone

In a paper published in the Royal Society’s journal “Biology Letters”, the researchers which included PhD student Travis Park (School of Biological Sciences, Monash University and Geosciences, Museum Victoria, both in Melbourne, Australia) explain how they borrowed a fossilised inner ear (cochlea) from the vertebrate fossil collection of the Smithsonian Institute and subjected the object to a CT scan (computerised tomography) to see inside and reveal the intricate structures that made up the hearing mechanism.

Student Travis Park Compares the Fossil Bone to the Inner Ear of an Extant Dolphin

The fossil cochlea (left) compared to the cochlea of a modern dolphin (right). Study suggests ancient toothed whales had echolocation.

Picture credit: Ben Healley

Comparing Extant with Extinct

Today’s dolphins and toothed whales produce high frequency sounds in their nasal passages. These are transmitted through air sinuses and a specialised organ, the melon, which consists of a mass of fatty tissue. It is the melon that propagates these sounds into the surrounding environment. These sounds “bounce” of objects in the animal’s surroundings and the reflected signals reach the inner ear (cochlea) via acoustic fat pads that are located at the end of the lower jaw bone and the middle ear.

The CT scan produced a three-dimensional image of the cochlea and an assessment of the ancient creature’s hearing abilities could then be made using the cochlea of modern, extant dolphin as a benchmark.

Ancient Whale Fossil Ear Bone

The 26-million-year-old fossil ear bone from a xenorophid (one of the earliest Odontocetes known) revealed internal structures that were remarkably similar to those found in extant toothed whales. The team concluded that ancient Oligocene whales had ears tuned for hearing high frequency sounds and therefore the ability to use echolocation.

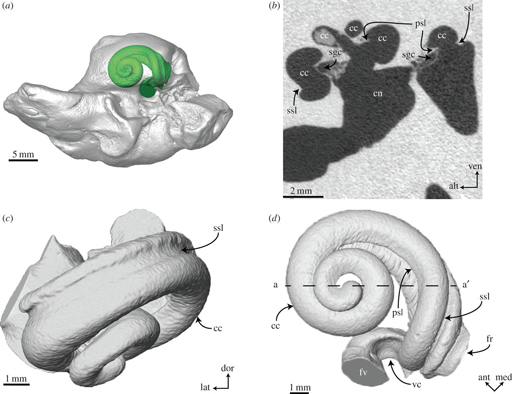

A Computer Model Generated from the CT Scan Reveals the Intricate Structure

Picture credit: Biology Letters

The picture above shows (a) the fossil bone with the inner ear structure superimposed on the transparent image, (b) a cross-sectional element from the CT scan showing key features of the inner ear. Images (c) and (d) are computer models created from the CT scan that shows the shape and structure of the ancient cochlea. From an assessment of the morphology and the structure of this cochlea, scientists have been able to determine the likely hearing abilities of the long extinct animal.

Commenting on the outcomes of the research, Travis Park stated:

“When I first looked at the inner ear of the xenorophid, I was blown away by just how similar this incredibly old toothed whale was to a modern echolocating dolphin.”

Intriguing Questions Remain

This means that even the most ancient ancestors of today’s toothed whales and dolphins had ears tuned for hearing high frequency sound, and therefore the ability to echolocate like their living relatives. It is likely that echolocation evolved in the ancestral Odontocetes but the fossil record is incomplete and a number of tantalising questions remain, as explained by co-author of the study Dr. Erich Fitzgerald (Museum Victoria):

“Our paper shows even the earliest known fossil Odontocetes have all the tools for echolocation seen in living dolphins. But they must have evolved from something that didn’t quite have all the tricks of the Odontocete trade. What were those animals like and how did they start down the path to sonic super senses? The quest for the origins of this extraordinary group of creatures continues.”

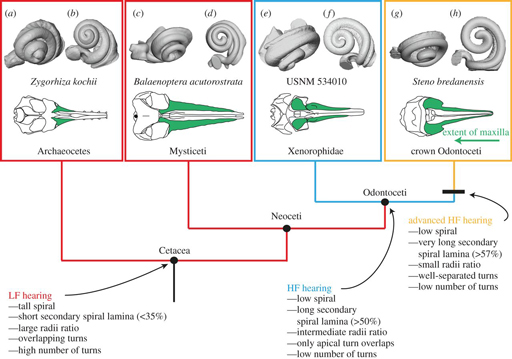

Plotting the Evolution of Echolocation in the Toothed Whales

Picture credit: Biology Letters

Charting the Evolution of the Inner Ear of Cetaceans

The diagram above charts the evolution of the inner ear in cetaceans (whales). The fossil bone used in the study has been assigned to the Xenorophidae family (fossil specimen used in the study is USNM-534010). The researchers suggest that over millions of years, the inner ear of these creatures evolved into organs more capable of hearing high frequency sounds.

Everything Dinosaur has written a number of articles that feature the research of Dr Fitzgerald (Senior Curator of Vertebrate Palaeontology at the Museum Victoria), he has certainly been involved in an eclectic range of studies including mapping Australia’s dinosaur diversity, looking at the origins of seals and examining the fossilised bones of a bird with “pseudo teeth” in its beak.

Australia’s diverse dinosaurs: Australia – A Dinosaur Melting Pot

The first seals of Australia: Australia’s First Seal – A Pliocene Pinniped

Giant bird with a toothy grin: Giant “Toothed” Birds Once Soared Over Australia

Leave A Comment