A newly published scientific paper documents the evolutionary history of burrowing vertebrates. Many animals alive today are able to live underground. Burrows are used for a variety of purposes. They are used for shelter, protection and for breeding. Understanding the origin and early evolution of fossorial vertebrates and the architecture and function of the burrows they excavate is an important component of the history of life on Earth. However, little research has been done into this area of vertebrate behaviour. A newly published scientific paper reviews the fossil record of vertebrate burrows and fossorial vertebrates.

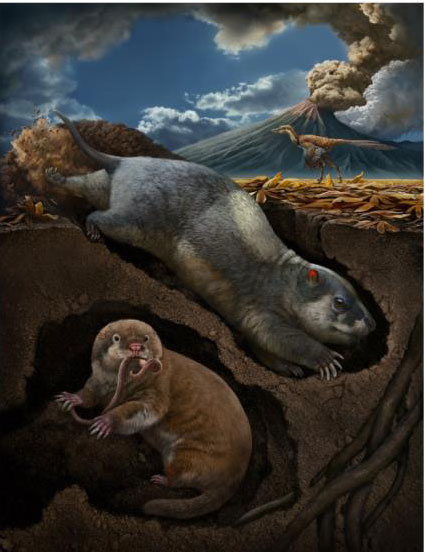

Picture credit: Zhao Chuang

The Evolution of Burrowing Vertebrates

Scientists including Dr Lorenzo Marchetti and colleagues from the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin analysed both body and trace fossils. The fossil material covered a large interval of geological time, from the Devonian to the Triassic. The research revealed an older appearance of several features related to burrowing behaviour and their relationship with global warming and mass extinctions.

During the Devonian-Carboniferous, burrows were probably used primarily for aestivation or temporary shelter and evidence of fossoriality is restricted so far to European and North American localities. During the Permian, fossoriality became geographically widespread and developed in new, distantly related vertebrate lineages. This is evidence of convergent evolution. Adaptations for burrowing and living underground being identified in both synapsids and diapsids.

The research highlights that lungfish (Dipnoi) were probably the first vertebrates to use burrows. Lungfish excavate burrows so that they have a protected environment in which they can spend long periods in a state of dormancy (aestivation). This behaviour probably first evolved in the Devonian.

Burrows Became Bigger and More Complex

The paper, published in “Earth-Science Reviews” outlines a trend for bigger and more complex burrows during the Palaeozoic and into the Mesozoic. Burrows became permanent shelters and breeding locations. The researchers link these developments to climate crises such as the Cisuralian aridification (Early Permian) and the end-Permian extinction event.

After the end-Permian mass extinction, vertebrate fossoriality became more common and widespread. This behaviour became a feature of continental environments and in more distal floodplain areas, probably as a consequence of changing fluvial regimes. In the Triassic, fossoriality is recorded in even more groups, such as the Temnospondyli and the Procolophonidae. In addition, evidence of burrow sharing by unrelated vertebrates appears. This indicates that burrowers were playing an increasing role as ecosystem engineers.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Origin and early evolution of vertebrate burrowing behaviour” by Lorenzo Marchetti, Mark J. MacDougall, Michael Buchwitz, Aurore Canoville, Max Herde, Christian F. Kammerer and Jörg Fröbisch published in Earth-Science Reviews.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment