A new study suggests that the key to the evolutionary success of the early mammals, was to stay small, eat insects and to reduce the number of bones in their skull. The reduction of mammalian skull bones led to a more efficient absorption of bite forces and this adaptation helped mammals to diversify and to ultimately dominate modern ecosystems.

The study, published in the academic journal “Communications Biology” contrasts the skulls of other vertebrates and mammalian ancestors with mammals known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous. In many vertebrate groups such as reptiles and fishes, the skull and lower jaw are composed of numerous bones. This configuration was also seen in the earliest ancestors of modern mammals that lived over 300 million years ago (Cynodontia). However, during evolution the number of bones in the skull was reduced.

A Reduction in Mammalian Skull Bones

Computer simulations based on three-dimensional skull models permitted the research team to examine bite forces and skull stresses. Their research demonstrates that reducing the number of skull bones did not lead to higher bite forces or increased skull strength as postulated previously.

Instead, the researchers, found that the skull shape of these early mammals redirected stresses during feeding in a more efficient way.

Lead author for the study, Dr Stephan Lautenschlager, Senior Lecturer for Palaeobiology (University of Birmingham) explained:

“Reducing the number of bones led to a redistribution of stresses in the skull of early mammals. Stress was redirected from the part of the skull housing the brain to the margins of the skull during feeding, which may have allowed for an increase in brain size.”

Switching Diets

The study, which also involved scientists from the University of Hull, Bristol University, the University of Chicago and the London Natural History Museum, demonstrated that alongside the reduction of skull bones, early mammals also became a lot smaller. Some Mammaliaformes for example, had skulls around 1 cm in length.

This miniaturisation considerably restricted the available food sources and early mammals adapted to feeding mostly on insects.

Dr Lautenschlager added:

“Changes to skull structure combined with mammals becoming smaller are linked with a dietary switch to consuming insects – allowing the subsequent diversification of mammals which led to development of the wide-range of creatures that we see around us today.”

Hadrocodium wui

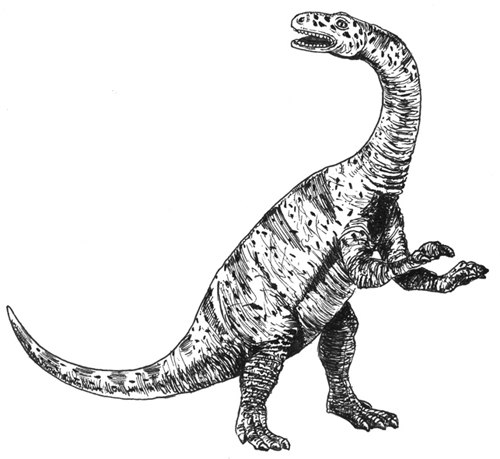

One of the mammaliaforms used in the study, is Hadrocodium wui fossils of which are known from the Early Jurassic (Sinemurian faunal stage) of China. At around ten centimetres long, this tiny animal was a very small and inconsequential member of the Lufeng Formation biota, which was dominated by dinosaurs such as Lufengosaurus.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The image (above) is a drawing of the Early Jurassic sauropodomorph Lufengosaurus.

For models and replicas of Early Jurassic dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals: CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Models and Figures.

However, H. wui is considered to be very close to the Mammaliaformes lineage that led directly to modern mammals (Mammalia).

To read an earlier blog post by Everything Dinosaur that examined how brain size might have increased in early mammals as a result of an improving sense of smell: Brain Size in Early Mammals Linked to Sense of Smell Development.

Staying Small and Eating Insects

The research team concludes that miniaturisation and staying small, combined with a reduction in skull bones and a switch to an insectivorous diet allowed the ancestors of modern mammals to thrive in the shadows of the Dinosauria. Having nocturnal habits may also have permitted these animals to carve out their own ecological niches in dinosaur dominated ecosystems.

It was not until dinosaurs became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, some 66 million years ago, that mammals had a chance to further diversify and reach the large range of body sizes seen in many extant mammals today.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Birmingham in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Functional reorganisation of the cranial skeleton during the cynodont–mammaliaform transition” by Stephan Lautenschlager, Michael J. Fagan, Zhe-Xi Luo, Charlotte M. Bird, Pamela Gill and Emily J. Rayfield published in Communications Biology.

Leave A Comment