Cephalopods Evolved 30 Million Years Earlier Than Previously Thought

Cephalopods those advanced sophisticated molluscs such as octopi, squid and cuttlefish evolved some thirty million years earlier than previously thought according to some new research published this week.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Cephalopods belong to the phylum Mollusca. Animals such as the octopus are regarded as highly intelligent, capable of complex behaviours and are regarded by many scientists as being as sophisticated, if not more so, than many vertebrates. The ancestors of the extant cephalopods around today originally possessed a chambered shell, indeed, the pearly nautilus still retains this feature (see above for a nautilus illustration). Researchers from Heidelberg University in collaboration with colleagues from the Bavarian Natural History Collections examined a 522 million-year-old outcrop from the Lower Cambrian Bonavista Formation exposed at Bacon Cove (south-eastern Newfoundland, Canada). Slices of the red sandstone which represent a shallow, marine depositional environment revealed tantalising glimpses of ancient Cambrian animals.

The Oldest Known Cephalopods

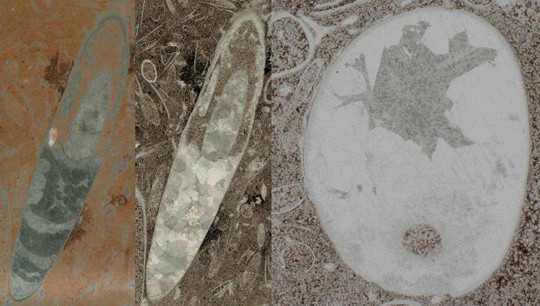

Tiny calcareous shells measuring no more than 14 mm high and around 3 mm wide discovered in cross-sections of the red sandstone rock are interpreted as representing phragmocones, part of the internal skeleton of a marine invertebrate. The researchers postulate that as similar structures are found in cephalopods, then these fossils represent the earliest evidence of the Cephalopoda.

An Extraordinary Find

Co-author of the research, Dr Gregor Austermann (Institute for Earth Sciences at Heidelberg University), commented:

“This find is extraordinary. In scientific circles it was long suspected that the evolution of these highly developed organisms had begun much earlier than hitherto assumed. But there was a lack of fossil evidence to back up this theory.”

Plectronoceras cambria

Although molecular studies had suggested that cephalopods evolved earlier than indicated by the fossil record, there was very little physical evidence to back this up. Many palaeontologists regard Plectronoceras cambria, fossils of which come from Texas limestones and date from the Middle/Late Cambrian as the earliest cephalopod. These Canadian fossils, if proved to represent the body fossils of cephalopods, push back the evolutionary origins of this important group by at least 30 million years.

The specimens described here may represent the earliest cephalopods capable of regulating the buoyancy of their shell through a siphuncle. This view supports the molecular studies that suggest that cephalopods originated in the Early Cambrian. These animals may have been the first to actively control their buoyancy and therefore to be capable of moving up and down the water column. It could be speculated that these fossils which are around 522 million years old, represent the remains of some of the first animals living above the sea floor (pelagic animals) and able to swim (nektonic).

The scientific paper: “A potential cephalopod from the early Cambrian of eastern Newfoundland, Canada” by Anne Hildenbrand, Gregor Austermann, Dirk Fuchs, Peter Bengtson and Wolfgang Stinnesbeck published in Communications Biology.

Visit the award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Prehistoric Animal Models and Toys.