The “Grandfather” of All Tortoises and Turtles

German Fossil Discovery Could be Transitional Fossil

How did the turtle get its shell? It sounds like the opening line from one of Aesop’s fables but in reality this question has been vexing palaeontologists for the best part of two hundred years. Thanks to some remarkable fossil discoveries from southern Germany (Baden-Württemberg) and the work of scientists from the Natural History Museum of Stuttgart and the Smithsonian Institute (National Museum of Natural History, Washington D.C.), we might be one step closer to solving this puzzle.

German Fossil Find

About thirty-five miles north-east of the city of Stuttgart, lies the picturesque town of Vellberg, there are a large number of quarries extracting Triassic-aged limestone and other materials in this locality, as in this part of the Germany, there are extensive outcrops of Lower Keuper sedimentary material.

In a band of claystone, which represents strata from the Erfurt Formation, (Lower Keuper stratigraphic unit), scientists have excavated eighteen specimens of a small reptile, the fossils of which, could represent a transitional fossil between basal Chelonians (turtles and tortoises) and the types of turtles and tortoises we see today.

Middle Triassic Rocks

The claystone represents sediments deposited at the bottom of a large lake that existed some 240 million years ago in the Middle Triassic (Ladinian faunal stage). Although the claystone layer is relatively thin, no more than fifteen centimetres deep at its thickest part, palaeontologists have been exploring these rocks since 1985 as the fossils they provide give a unique insight into the fauna of this part of the world a few million years after the End Permian extinction event, at around the time of the very first dinosaurs.

Dr Rainer Schoch at the Excavation Site (Erfurt Formation)

Picture credit: Dr Rainer Schoch/Natural History Museum of Stuttgart

Pappochelys rosinae

The reptile has been named Pappochelys rosinae, the genus name translates from the Greek meaning “grandfather turtle”, the species name honours Isabell Rosin of the Natural History Museum of Stuttgart as she was responsible for preparing the fossil specimens for study. This little reptile measured around twenty centimetres in length, the long tail made up about fifty percent of the total body length.

Anatomical features indicate that this reptile is a transitional animal from the more primitive and older Eunotosaurus known from strata dating from approximately 260 million years ago and the more recent Odontochelys, whose fossils come from Chinese rocks and date from about 220 million years ago.

Pappochelys

Pappochelys could be an intermediary form in between Eunotosaurus and Odontochelys. It helps to fill the forty million year gap in Chelonian fossils. Whilst Odontochelys, lacked the full turtle shell (carapace) it did possess a hard, flat underbelly (plastron). P. rosinae lacks a plastron, but the gastralia (belly ribs) on its underside are broader and closer to fusing than in Eunotosaurus.

To read about the discovery of Eunotosaurus: An Insight into Chelonian Evolution.

Associated Post Cranial Material of Pappochelys rosinae

Picture credit: Natural History Museum of Stuttgart

Hans-Dieter Sues, (Curator of Vertebrate Palaeontology, at the National Museum of Natural History, Washington D.C.) explained:

“In the case of Pappochelys, we see that its belly was protected by an array of rod-like bones, some of which are already fused to each other. Such a stage in the evolution of the turtle shell has long been predicted by embryological research on present-day turtles but never observed in fossils – until now.”

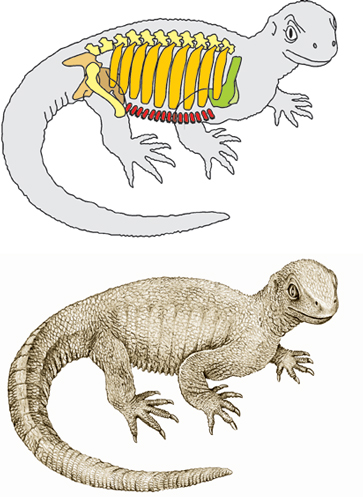

An Illustration of Pappochelys and Outline Plan of Key Bones

Illustration and outline plan of bones – ribs (mustard), gastralia (red), shoulder girdle (green), pelvis (brown), femur and vertebrae (yellow)

Picture credit: Natural History Museum of Stuttgart

Thickened Ribs

The diagram shows the thickened trunk ribs of this ancient reptile and the lacustrine (lake) deposit might provide a clue as to why such creatures eventually evolved a hard shell. The bones are thickened and more dense, if this animal was semi-aquatic, then the heavier bones would help to provide ballast and counter the animal’s natural buoyancy in water.

The more robust, heavier bones might have helped this reptile to dive deeper and to stay underwater for longer. The pelvis and the shoulder girdle are very similar to those found in Odontochelys, which is regarded by many scientists as the earliest true turtle.

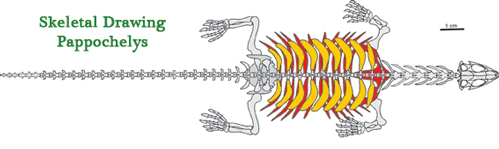

A Dorsal view of the Bauplan Showing Modified Ribs and Gastralia

Picture credit: Natural History Museum of Stuttgart

The picture above shows a skeletal reconstruction of Pappochelys. The ribs (mustard) and the gastralia (red).

Evolution of Turtles

Dr Sues outlined the anatomical developments leading to modern-day turtles that could be traced from the fragmentary fossils found at Vellberg. The paper on these specimens, which Dr Sues co-authored has just been published in “Nature”.

He stated:

“It [Pappochelys] has real beginnings of the belly shell developing, little rib-like structures beginning to fuse together into larger plates and then ultimately making up the belly shell [plastron].”

Where do the Tortoises and Turtles Fit in with Other Reptile Groups?

The origins of the Chelonia (turtles and tortoises) remain controversial. More modern Chelonia, such as those genera still around today do not have teeth. Instead, they have a beak. Pappochelys had teeth, (some cranial material including jawbones and teeth have been found) and it is known that Odontochelys also had teeth (the genus name translates as “toothed turtle with half a shell”). However, scientists have long argued where in the Order Reptilia the Chelonia actually sit.

They are regarded as a very ancient group of reptiles. It had been thought that turtles and tortoises were descended from ancient Parareptiles, but the skull bones of Pappochelys reveal an affinity to the diapsid reptiles, a wide-ranging group that includes lizards, snakes, crocodiles as well as extinct marine reptiles and the Dinosauria.

Implictions for Reptile Taxonomy

It had been thought that tortoises and turtles were anapsids, lacking temporal fenestrae (holes behind the eye socket in the skull, but the Pappochelys cranial material shows a pair of openings in the skull behind each eye socket. This suggests that the Chelonia are not descended from parareptiles but have phylogenetic affinities to the diapsids. This places them in the same clade as lizards and snakes.