New Evidence of Velociraptor Feeding Behaviour – Scavenging the Carcase of a Protoceratops

Fossil Find Shows Evidence of a Velociraptor Feeding upon Another Dinosaur

Velociraptor that speedy Late Cretaceous predator with its sickle-shaped “killing claw” on the second toe of each foot, plus a jaw lined with more teeth than a T. rex has a deserved reputation for being vicious amongst dinosaur fans and scientists. However, with the exception of one amazing fossil find made in 1971, palaeontologists had little evidence of what this turkey-sized animal fed on, but now that has changed thanks to a remarkable discovery made in China.

A Fight to the Death

Picture credit: Polish Academy of Sciences

The picture above shows the partial excavation of one of the most famous dinosaur fossils discovered to date. A Polish expedition exploring Late Cretaceous strata at a site called Toogreeg in the Gobi desert of Mongolia, uncovered evidence of a fight to the death between two dinosaurs.

A predatory Velociraptor (seen on the right of the picture) has been preserved alongside a Protoceratops (herbivore). The tangled fossil shows that the Velociraptor had grasped the plant-eater’s head and was delivering vicious kicks to the underbelly of the Protoceratops, whilst the Protoceratops gripped the attacker’s arm in its strong beak. It is likely that this duel led to both animals being mortally wounded, their remains being engulfed in sand and preserved. This remarkable fossil is known as “the fighting dinosaurs” and is one of very few specimens that show fighting behaviour in Dinosauria.

However, a team of researchers have found fossil fragments of Velociraptor teeth alongside the scattered bones of a sub-adult Protoceratops and from the scratches on the bones, it seems that evidence of Velociraptor feeding behaviour has been found. The teeth marks on the herbivore’s bones suggest that a Velociraptor scavenged the Protoceratops carcase.

Despite the “smoking gun” evidence of the 1971 discovery, scientists were unsure how often Velociraptor predated upon and fed upon other dinosaurs such as Protoceratops. Velociraptor, with their misleading over-sized depiction in the Jurassic Park trilogy, were actually quite small theropods. A fully grown Velociraptor (V. mongoliensis) could weigh as much as 15 kilogrammes and perhaps stood a little over a metre tall. Protoceratops, despite being much slower than Velociraptor would have had size and strength on its side.

Adult Protoceratops would have reached lengths in excess of six feet and their squat, powerful bodies could have weighed as much as 400 kilogrammes. Scientists have speculated that dinosaurs such as Velociraptor may have fed mainly on smaller animals such as lizards, baby dinosaurs and birds, although if they hunted in a pack they would have been capable of bringing down much larger quarry.

Protoceratops fossils in this particular rock strata are the commonest large vertebrate fossils found. Fossils of Velociraptor, especially their teeth have been found in this strata also, this may indicate that the predatory Velociraptor interacted frequently with the relatively common herbivore Protoceratops.

This new discovery, a paper of which is due to be published shortly in the scientific journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, suggests that Velociraptors may have regularly fed on Protoceratops. The finding of Velociraptor teeth in association with Protoceratops bones that show scratches made from feeding dinosaurs indicates that Velociraptor may have regularly dined on Protoceratops, either by hunting or scavenging from the bodies of those animals that had already perished.

Dr David Hone of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing) made the new discovery in Upper Cretaceous deposits at Bayan Mandahu, in Inner Mongolia, China. His colleague Dr Jonah Choiniere found a mass of badly eroded Protoceratops bones, amongst them lay two Velociraptorine-like teeth. The scientists were keen to analyse the dinosaur bones to see if any signs of feeding behaviour had been preserved. Dr Hone and colleagues Dr Mike Pittman and Dr Corwin Sullivan were able to identify a number of bite marks and scratches that indicated that the carcase had been scavenged by a Velociraptor-like dinosaur, the teeth were broken and shed as it fed.

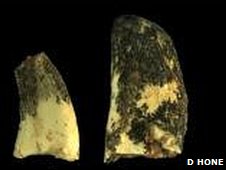

Broken Velociraptorine Teeth find at the Site

Picture credit: Dr. David Hone

The picture shows the shed teeth found in association with the the Protoceratops fossils. These tiny teeth are broken at the tip and indicate that they were lost when the Velociraptor-like animal bit into the hard bones of the dead dinosaur. Finding evidence such as this is extremely difficult, the teeth of these dromaeosaurs are extremely small and fragmentary remains of teeth are notoriously hard to spot, even when using fine screening sieves to help recover the fossils.

Bite Marks on the Protoceratops Fossil Bone

Picture credit: Dr. David Hone

The three white arrows in the picture show the strong scratches in the fossilised bone, indications that the Velociraptor scavenged the carcase. The bite marks match the sort of impressions that Velociraptor teeth would have made. As the Protoceratops was quite large (nearly fully grown) and since the bite marks were found on the jaw bones, it is likely that this fossil evidence represents scavenging behaviour and not hunting behaviour.

Dr Hone commented:

“The marks were on and around bits of the jaw. Protoceratops probably weighed many times what a Velociraptor did, with lots of muscle to eat. Why scrape away at the jaws, where there’s not much muscle, so heavily that you scratch the bone and lose teeth unless there was not much else there?”

This data suggests that a Velociraptor-like animal discovered the carcase, perhaps scenting the rotting flesh from many miles away and then it fed on what meat remained on the animal.

An Artists Impression of the Feeding Velociraptorine

Picture credit: Brett Booth

Dr Hone stated:

“In short, this looks like scavenging as the animal would be feeding on the haunches and guts first, not the cheeks”.

Protoceratops did have powerful jaws, it is perhaps possible that the cheeks of this animal were quite fleshy and one of the choicest cuts of meat. Flesh from the cheeks of animals such as cows is seen as a delicacy and revered by many butchers who regard this part of the carcase as a most flavoursome and tasty cut. We know of many local butchers who remove the cheeks from a cow whilst butchering the rest of the carcase, taking home their prize. Could the cheeks of a Protoceratops have been a choice cut for a Velociraptor?

Such feeding behaviour is not common in extent animals, most small scavengers attempt to grab what they can from where they can, after all, if they have been attracted to the carcase then some other larger beastie may be on its way to gate crash events.

Commenting on the 1971 Polish discovery Dr Hone said:

“The fighting dinosaurs suggests predation. Combine the two and we have good evidence for both behaviours. Animals like Velociraptor were probably feeding on animals like Protoceratops regularly, probably including both predation and scavenging.”

No doubt this new evidence will add spice to the perennial argument surrounding the feeding habits of Theropods, particularly the larger ones such as the late Tyrannosauridae. Did these animals scavenge most of their meals or were they active hunters? Almost all living carnivores do a bit of both, hunting but not being averse to free lunch should they find a corpse upon which they can feed.

Discussing this point Dr Hone stated:

“It is a question of degree. Lions mostly predate, whilst jackals mostly scavenge.”

This new fossil discovery helps confirm what many researchers have long suspected about how carnivorous dinosaurs interacted with their plant-eating counterparts.

Dr Hone concluded:

“Even the most dedicated predator won’t turn down a free meal if they chance across a dead animal with a few bits of meat still attached, and this looks like the case here.”

The Beasts of the Mesozoic model series contains a variety of dromaeosaurid figures: Beasts of the Mesozoic Models and Figures.