Analysis of Compound Eye Fossil Indicates that Apex Predator had Fantastic Vision

Back in June, team members at Everything Dinosaur wrote a brief article on the remarkable research being undertaken by South Australian Museum and University of Adelaide scientists working on fossils of compound eyes dating from more than 500 million years ago. The fossils from the Emu Bay area of Kangaroo Island show that by the Middle Cambrian some invertebrates had evolved very sophisticated vision, much better than many types of extant insects and crustaceans and perhaps at least as good as those aerial masters the dragonflies.

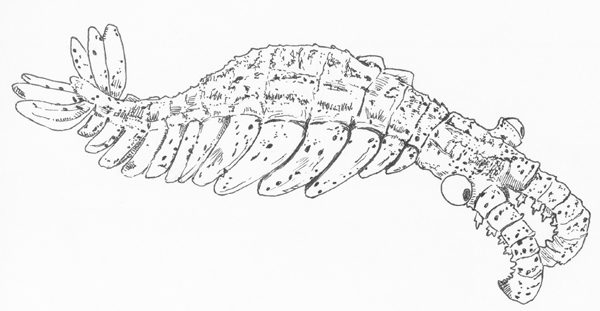

An Illustration of Anomalocaris

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

This months edition of the scientific journal “Nature” will contain a feature on the work of the research team and the front cover will consist of an artist’s impression of the super predator that the compound eyes probably belonged to – the world’s first apex predator – Anomalocaris.

To read the earlier article on the Kangaroo Island fossils: World’s Oldest Fossil Eye Discovered in Australia.

The international team behind this study includes two Adelaide researchers Associate Professor Michael Lee (South Australia Museum and University of Adelaide) and Dr Jim Jago (South Australia Museum). From our understanding of the fossil evidence, the advanced compound eye probably belonged to the largest predator known from strata dating from the same geological period – Anomalocaris. This invertebrate, a member of the Arthropoda, the largest phylum of animals is distantly related to crustaceans such as lobsters and shrimps.

At up to a metre in length, this is the largest animal known from Cambrian strata. Fossils ascribed to Anomalocaris have been found in Southern China as well as these from Australia that the scientists studied, but perhaps most famously, this fierce predator is associated with the Burgess Shale deposits of British Columbia (Canada).

Anomalocaris

Anomalocaris is the stuff of nightmares and sci-fi movies. It is considered to be at the top of the earliest food chains because of its large body size, formidable grasping claws armed with sharp spikes and a circular mouth positioned under the head with its razor-sharp serrations.

Fossils of trilobites contemporaneous to Anomalocaris fossil material are testament to this formidable predator. Some of the trilobite fossils show signs of severe damage and there has even been some five hundred million year old fossilised poo (coprolite) containing crushed and smashed pieces of trilobite exoskeleton – the remains of an Amomalocaris meal perhaps?

The discovery of superbly preserved eye fossils, the remains of the calcite based compound eyes that were supported on the end of a stiff stalk each side of the head, show astonishing detail of the optical design. Having excellent vision, far better than its prey would have given animals like Anomalocaris a huge advantage when hunting. Bio-mechanical studies have shown that Anomalocaris was nektonic (free swimming), but not a very fast swimmer. However, with much more advanced eyesight than most of its prey, this armoured giant of the Cambrian seas would have been a very effective hunter.

Compound Eyes

The fossils represent compound eyes – the multi-faceted variety seen in arthropods such as flies, crabs and such like. However, the fossils represent compound eyes that are up to three centimetres in diameter. They are amongst the largest to have compound eyes ever to have evolved. Each eye contains up to 16,000 individual lenses, that is like having two 16-kilo pixel cameras perched on stalks either side of the head. This would have given this predator excellent almost 300 degree vision.

The number of lenses and other aspects of their optical design suggest that Anomalocaris would have seen its world with exceptional clarity whilst hunting in well-lit waters. Only a few arthropods, such as modern predatory dragonflies, have similar resolution.

The international research team conclude that the existence of highly sophisticated, visual hunters within Cambrian communities would have accelerated the predator/prey “arms race” that began during this important phase in early animal evolution over half a billion years ago. Such a predator/prey relationship would have helped to speed up evolution, perhaps helping to explain the rapid diversification of marine animal forms during this geological period.

Powerful Compound Eyes

The discovery of powerful compound eyes in Anomalocaris confirms it is a close relative of arthropods, and has other far-reaching evolutionary implications. It demonstrates that this particular type of visual organ appeared and was elaborated upon very early during arthropod evolution, originating before other characteristic anatomical structures of this group, such as a hardened exoskeleton and walking legs.

The superb artwork, that is featured on the front cover of “Nature” was painted by Adelaide based artist Katrina Kenny. Katrina has a passion for fossils and her love of the subject plus her skills in biological illustration have helped bring back this fearsome predator of the Cambrian. The painting was commissioned by the University of Adelaide.

The South Australia Museum and the University of Adelaide have summarised the research in a short video.

To view models and replicas of ancient arthropods, including Anomalocaris (whilst stocks last): CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Popular Figures.

Leave A Comment