Dinosaur Parasites Preserved in 99-million-year-old Amber

Fossilised ticks discovered trapped and preserved in amber show that these parasites sucked the blood of feathered dinosaurs almost 100 million years ago, according to a new article published in the scientific journal “Nature Communications”. The amber nodule containing the blood-sucking ticks provides the first direct evidence to support the idea that feathered dinosaurs, just like birds today, had to endure blood-sucking parasites. As a result of this research, a new species of tick has been named “Dracula’s terrible tick” – Deinocroton draculi.

Feathered Dinosaur Parasites

Modern ticks pass diseases onto their host, this discovery provides evidence that as well as having to deal with parasites, it is likely these ticks and their feeding resulted in the transmission of disease from the invertebrate to their dinosaur host.

The Discovery of Blood-sucking Ticks in Association with Dinosaur Feathers

Picture credit: Nature Communications

Cornupalpatum burmanicum

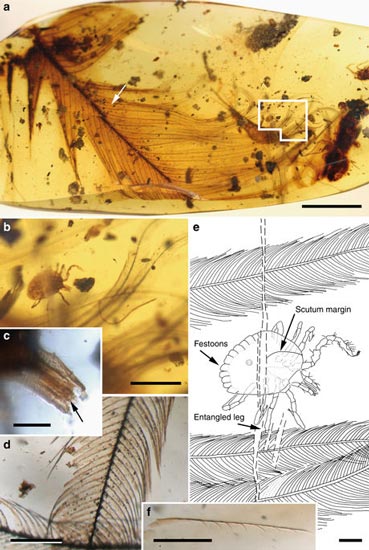

The image above shows the hard tick identified as Cornupalpatum burmanicum entangled in a pennaceous feather. Photograph (a) shows an image of the amber nodule, scale bar 5 mm, the area in the white box is highlighted in (b) allowing the tick that was entangled in the barbs of the feather to be clearly seen (scale bar 1 mm).

Photograph (c) shows a close-up view of the tick’s capitulum (feeding apparatus), the teeth are highlighted by a black arrow (scale bar 0.1 mm). Picture (d) shows a view of a barb on the feather, scale bar 0.2 mm, whilst the line drawing (e) shows a dorsal view of the tick and the entangled legs. Photograph (f) shows a close-up view of the hooklets associated with the barb on the feather, the tick became ensnared in these hooklets and trapped, scale bar 0.2 mm.

Fossils of parasites are extremely rare, especially those found with direct evidence which suggests their host. However, preserved inside a piece of Burmite (amber from Myanmar), which was formed around 100 million-years-ago, researchers found the perfectly preserved remains of a tick tangled up in a feather along with the remains of other ticks, providing a valuable insight into the lives of feathered dinosaurs.

A Jurassic Park Scenario?

Although the tick may contain dinosaur blood, the antiseptic and antibacterial properties of the amber (after all, amber is preserved tree resin and this resin is produced by certain types of trees to protect them from infection), all attempts to identify organic remains such as dinosaur DNA from amber have proved unsuccessful.

Lead author of the study, Enrique Peñalver from the Spanish Geological Survey (IGME), explained the significance of the fossil find:

“Ticks are infamous blood-sucking, parasitic organisms, having a tremendous impact on the health of humans, livestock, pets, and even wildlife, but until now clear evidence of their role in deep time has been lacking.”

Remarkable Amber from Myanmar

Over the last few years, a number of remarkable fossil discoveries have been made as scientists study amber nodules from Myanmar (formerly known as Burma). For example, in December 2016, Everything Dinosaur reported on the discovery of a partial dinosaur tail preserved in amber, whilst in June 2017, this blog site reported upon the discovery of the remains of a baby prehistoric bird that also became entombed in amber.

Dinosaur tail found in Burmite: The Tale of a Dinosaur Tail.

Baby Bird (Enantiornithine bird) preserved in amber: Watch the Birdie! Enantiornithine Bird Preserved in Amber.

The amber was formed in the early part of the Cenomanian faunal stage of the Late Cretaceous. Northern Burma was covered in a temperate forest during this phase of the Cretaceous, tree resin trapped all kinds of creatures and plant material providing palaeontologists with a fascinating insight into the flora and fauna of a Cretaceous ecosystem.

The researchers identified five different ticks, one is grasping the dinosaur feather and has been identified as an example of Cornupalpatum burmanicum, a tick belonging to the Ixodidae family. It was a “hard” tick, it had a tough shield (scutum) on its back which protected the arthropod from predators. The others including one engorged with blood have been assigned to the new species Deinocroton draculi.

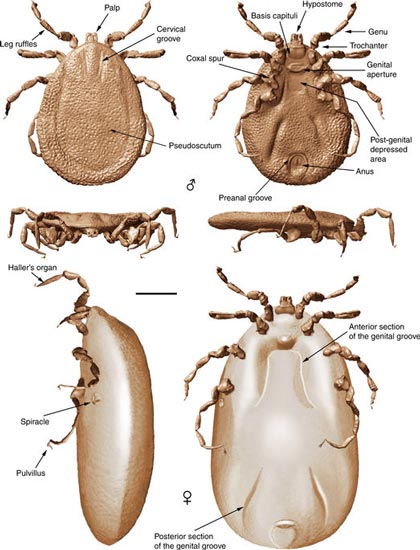

Illustrations of Two of the Ticks (Male and Female D. draculi)

Picture credit: Nature Communications

Co-author of the study, Dr Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente (Oxford University Museum of Natural History) commented:

“The fossil record tells us that feathers like the one we have studied were already present on a wide range of theropod dinosaurs, a group which included ground-running forms without flying ability, as well as bird-like dinosaurs capable of powered flight. So, although we can’t be sure what kind of dinosaur the tick was feeding on, the Cretaceous age of the Burmese amber confirms that the feather certainly did not belong to a modern bird, as these appeared much later in theropod evolution according to current fossil and molecular evidence”.

Engorged with Blood

The tick that has recently fed shows an eight-fold increase in body volume. This suggests that D. draculi fed quickly. It will not be possible to analyse the blood as this tick was only partially immersed in the sticky tree resin and during the fossilisation process the body contents were altered by mineral deposition.

Indirect evidence of a probable dinosaur host is provided in the form of hair-like structures (setae) from the larvae of skin beetles (dermestids), found attached to the other two Deinocroton ticks preserved together. Dermestids feed in nests, on debris such as shed feathers, skin and hair from the nest’s residents. As no mammal hairs have yet to be found in Burmite (or indeed any Cretaceous amber), the presence of skin beetle setae on the two Deinocroton draculi specimens suggests that the ticks’ host was a feathered dinosaur.

A Three-dimensional Model of the Newly Described Cretaceous Tick (Deinocroton draculi)

Picture credit: Oscar Sanisidro (University of Kansas)

Another author of the scientific paper, Dr David Grimaldi (American Museum of Natural History, New York) explained:

“The simultaneous entrapment of two external parasites – the ticks – is extraordinary, and can be best explained if they had a nest-inhabiting ecology as some modern ticks do, living in the host’s nest or in their own nest nearby.”

The discovery of these ticks provides indirect and direct evidence that ticks have been parasitising and sucking the blood from dinosaurs within the evolutionary lineage leading to extant Aves for almost 100 million-years.

The scientific paper: “Ticks Parasitised Feathered Dinosaurs as Revealed by Cretaceous Amber Assemblages” by Enrique Peñalver, Antonio Arillo, Xavier Delclòs, David Peris, David A. Grimaldi, Scott R. Anderson, Paul C. Nascimbene & Ricardo Pérez-de la Fuente published in the journal “Nature Communications”.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the help of a press release from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History in the compilation of this article.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment