Amazing Hamipterus Nesting Ground Discovery

Pterosaurs Even More Like Birds

Pterosaurs like birds, were capable of powered flight. It seems that command of the skies is not the only thing that these two types of vertebrate had in common. Thanks to a remarkable series of discoveries from the remote Turpan-Hami Basin located in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (north-western China), palaeontologists have learned that pterosaurs, like many living birds nested in colonies, that they had preferred nesting sites and when young, pterosaurs needed a degree of parental care, just like many species of birds today.

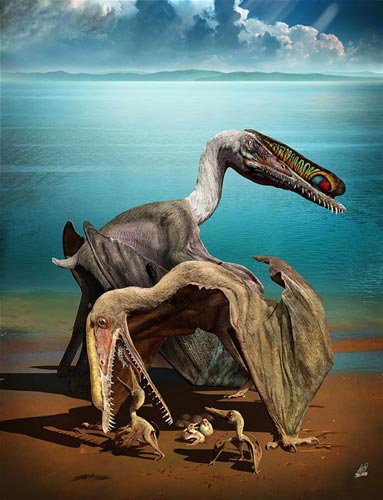

Pterosaur Nesting Colony (Hamipterus tianshanensis)

Picture credit: Zhao Chuang

Hundreds of Pterosaur Eggs Discovered

Writing in the journal “Science”, researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences along with collaborators from a number of research institutions in Brazil have published a paper describing the discovery of 215 pterosaur eggs, 16 of which contain the remains of embryos. The eggs and the numerous fossil bones associated with the site have been attributed to Hamipterus tianshanensis, a flying reptile first named and described in 2014 whose exact taxonomic position in the pterosaur family tree remains open to debate.

That point notwithstanding, H. tianshanensis has been propelled to super-stardom, like a Pteranodon taking to the air, representing one of the most significant Pterosauria discoveries made to date.

An Assemblage of Pterosaur Fossils

Picture credit: Xinhua/Wang Xiaolin

Pterosaur Nesting Grounds

Significantly, the number of eggs discovered are far too many to have been laid by a single female. This suggests that these flying reptiles nested in colonies and furthermore, the overlaying of multiple clutches of eggs indicates that pterosaurs, like many birds today, returned to the same nesting sites each year. As the authors conclude, “the similarity between these groups goes beyond wings”.

The Remains of Numerous Individuals at the Site

Picture credit: Xinhua/Alexander Kellner

Three-Dimensional Fossil Egg Preservation

The eggs were not laid at the location where they were discovered. This exceptional Lagerstätte preserves a series of tragic events, it seems that periodically, the nesting area was subjected to flooding as a result of seasonal storms. Many of the eggs have been preserved in three dimensions, caused by the encroachment of sediment.

Computed tomography scans have revealed minute details of some of the embryos preserved within the eggs. For example, an almost complete skeleton of a hatchling shows that bones related to flight were less developed than bones of the hind limb, indicating that new-borns might have been able to walk but not fly.

The front limb bones lack ossification and had yet to fully form, whilst the leg bones such as the femora are well developed. This suggests that the young pterosaurs were unable to fly, but not completely helpless, their strong legs would have meant that they would not have been stuck in the nest but quite capable of locomotion. However, these new insights have led the palaeontologists to conclude that, in the case of Hamipterus at least, the offspring were less precocious than previously assumed.

In short, mum and dad (coming to that bit next), had to take care of their young, bring food to them and protect them from predators.

Evidence Suggests that Pterosaurs Cared for their Young

Picture credit: Zhao Chuang

The Significance of Dad

Hamipterus tianshanensis was named and described three years ago. This fossil location had been discovered several years before, but the pterosaur body fossils and the associated pterosaur egg material (forty specimens and five eggs), were not scientifically described until 2014.

In the 2014 paper (Wang et al), which was written by many of the scientists involved in this latest study, it was postulated that differences in head crest shape or size helped to distinguish males from females.

It was proposed that specimens with larger skull crests were males. This suggests sexual dimorphism in this species and, if this idea is taken a little further, it implies that the males may have played a role in helping to bring up the next generation. After all, fossilised remains of what might represent adult males have been swept together with the nest site fossils. Many male birds share parental responsibilities and lots of extant Aves such as the Wandering Albatross (Diomedea exulans) for instance, pair for life. Perhaps, adult pterosaurs also had monogamous behaviour.

A Close-up View of the Preserved Leathery Egg of Hamipterus

Picture credit: Xinhua/Wang Xiaolin

Inferring Behaviours

To what degree the Pterosauria and Aves share behaviours remains a controversial area. Further research into the remarkable Hamipterus Lagerstätte has greatly increased our knowledge about flying reptiles but we must be careful not to infer or imply too much from the fossil evidence. The scientists conclude that the discovery of all these bones and fossilised eggs supports the idea that these pterosaurs nested in colonies and that they returned to a favoured nesting site to breed.

Two of the Authors of the Scientific Paper Inspect Part of the Remote Dig Site

Picture credit: Xinhua

The scientific paper: “Egg Accumulation with 3D Embryos Provides Insight into the Life History of a Pterosaur” by Xiaolin Wang, Alexander W. A. Kellner, Shunxing Jiang, Xin Cheng, Qiang Wang, Yingxia Ma, Yahefujiang Paidoula, Taissa Rodrigues, He Chen, Juliana M. Sayão, Ning Li, Jialiang Zhang, Renan A. M. Bantim, Xi Meng, Xinjun Zhang, Rui Qiu and Zhonghe Zhou published in the journal “Science”.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Visit Everything Dinosaur.