Shingopana songwensis – Hinting at a Diverse African Titanosaur Biota

A team of international scientists including Dr Eric Gorscak, a recent PhD graduate of Ohio University and now a post-doctoral researcher at the Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago, USA), have identified a new species of Cretaceous long-necked dinosaur from south-western Tanzania. This new species of plant-eating giant has been named Shingopana songwensis and its discovery helps to demonstrate how diverse the dinosaur fauna was in southern Africa during the Cretaceous.

Writing in the Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology, the scientists, describe the new titanosaur, one that shows anatomical affinities to South American titanosaurs, indicating that Shingopana was more closely related to South American dinosaurs than it was to those species known from Africa.

The first fossils of this new dinosaur were found in 2002 by scientists affiliated with the Rukwa Rift Basin Project, an international effort led by Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine researchers Patrick O’Connor and Nancy Stevens. Other elements associated with the specimen were found over the next two years. All the fossils come from Namba Member of the Galula Formation.

An Illustration of Shingopana songwensis

Picture credit: Mark Witton

In the beautiful illustration created by palaeoartist Mark Witton, (above), a herd of Shingopana can be seen in the background, whilst the foreground is dominated by the rotting carcass of S. songwensis. A crocodylomorph is scavenging and the corpse has attracted the attention of numerous carrion beetles some of which can be clearly seen on an exposed rib bone.

The Enigmatic Galula Formation

The Galula Formation consists of a 600-3000 metre-thick sequence of amalgamated, braided fluvial deposits that were deposited across an extensive braidplain system via multiple parallel channels that had their source in the highlands of Zambia and Malawi. Dating these mainly sandstone sediments has proved challenging. Magnetostratigraphic studies place these deposits, split into two main members (the Namba and the geologically older Mtuka members), as being no older than mid-Late Cretaceous (Turonian-Campanian) for the Namba and constraining the Mtuka to the Middle Cretaceous (Aptian – Cenomanian). Although most of the vertebrate fossils discovered to date are fragmentary in nature, they hint at a rich biota made up of numerous crocodyliforms, turtles, theropods, sauropods plus evidence of several types of small mammal.

The fossils represent around 10% of the total skeleton. They were excavated from a single location and the fossils were disarticulated. A comparison of the left humerus to that of the contemporaneous but not closely related Malawisaurus suggests that Shingopana might have exceeded 16 metres in length, although other media sources report that this dinosaur was under ten metres in length. Other fossils include part of the jaw (left angular), part of the hip girdle, cervical and dorsal ribs along with neck bones (cervical vertebrae).

“Wide Neck” from the Songwe Region

The name of this new dinosaur (Shingopana songwensis), is derived from the local Swahili term “shingopana” for “wide neck”. The neural spine of the cervical ribs show a bulbous expansion, that led the researchers to assign this new genus to the Aeolosaurini, all the dinosaurs assigned to this clade (as far as we at Everything Dinosaur know), come from South America. The trivial name honours the location of the discovery, the Songwe region of the Great Rift Valley. Shingopana is the first African titanosaur that is closely related to Aeolosaurines.

Shingopana Fossil Bones Being Excavated and Prepared for Field Removal

Picture credit: Nancy Stevens

Commenting on the phylogeny of Shingopana, Dr Gorscak stated:

“There are anatomical features present only in Shingopana and in several South American titanosaurs, but not in other African titanosaurs. Shingopana had siblings in South America, whereas other African titanosaurs were only distant cousins.”

This discovery supports the hypothesis that the biota of southern and northern Africa were very different during the Cretaceous. Dinosaurs from the southern part of the continent were probably more closely related to South American dinosaurs than they were to the dinosaurs that lived on the northern part of Africa. Shingopana co-existed with another titanosaur, Rukwatitan bisepultus, but just like Malawisaurus, Rukwatitan was not closely related to Shingopana.

To read Everything Dinosaur’s article on the discovery and naming of Rukwatitan bisepultus: A Rare African Giant – Rukwatitan.

Dinosaur CSI

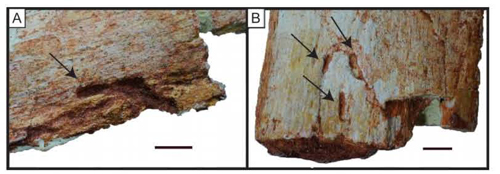

The researchers noted that the bones had been weathered prior to fossilisation. The fossils show extensive borings, most likely caused by the activities of carrion beetles. The presence of these trace fossils are particularly notable on the cervical vertebrae, the humerus and the pubis. Over 150 separate bore holes were identified on 10 different bones from the dig site. Insect borings such as these give palaeontologists an opportunity to reconstruct the timing of death and the taphonomy (the fossilisation process), of the fossil material.

A Close-up View of Rib Bones with Trace Fossils (Insect Borings)

Picture credit: Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology

A Changing Cretaceous Landscape

As the super-continent of Gondwana began to break up, so Madagascar and Antarctica split from the landmass that we now know as southern Africa. This was followed by the gradual northward “unzipping” of South America. Northern Africa maintained a land bridge with South America, but southern Africa slowly became more isolated until the continents completely separated around 105 – 95 million years ago.

Other factors such as terrain and climate may have further isolated southern Africa. The discovery of Shingopana highlights the different regional faunas between north Africa and southern Africa and suggests that tectonically driven separation of the landmasses may have influenced the development of progressively isolated southern African faunas throughout the Cretaceous.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment