The Oldest Elasmosaurid in Town a New Basal Elasmosaurid is Described

A New Basal Elasmosaurid is Described (Lagenanectes richterae)

It has been a busy week for Sven Sachs of the Bielefeld Natural History Museum, Germany. A few days ago, Everything Dinosaur blogged about the discovery of the largest Ichthyosaurus specimen known (I. somersetensis), Sven was a co-author of the scientific paper published in the “Acta Palaeontologica Polonica”. Today, we feature another marine reptile discovery, this time it concerns one of the oldest-known members of the Elasmosauridae and Sven is one of the co-authors of this paper too.

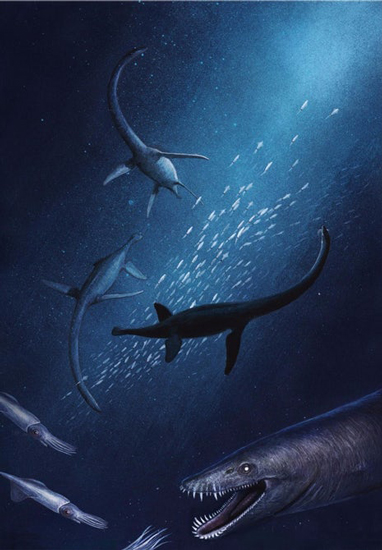

An Artist’s Impression of the Newly Described Basal Elasmosaurid Lagenanectes richterae

Picture credit: Joschua Knuppe

A Marine Reptile Discovery

Writing in the “Journal of Vertebrae Paleontology”, the researchers Jahn Hornung and Benjamin Kear as well as Sachs, describe a previously unrecognised new species of elasmosaur from Lower Cretaceous sediments at Sarstedt near Hannover (northern Germany). The Elasmosauridae are a diverse family of plesiosaurs that are characterised by the extraordinarily long necks, with some specimens having more than seventy cervical vertebrae. They were predominately piscivores, preying on small fish and squid, which they swallowed whole.

Older definitions of the Elasmosauridae included many Jurassic long-necked forms, however, most palaeontologists now restrict elasmosaurids to just the Cretaceous taxa.

The fossilised bones of the marine reptile were unearthed in 1964 as workmen were excavating a clay pit near the town of Sarstedt. The fossils consist of a partial skull (cranium and mandible), the atlas-axis complex, additional cervical vertebrae, caudal vertebrae, an ilium, and limb elements. The material was added to the vertebrate fossil collection of the Lower Saxony State Museum (Hannover), where it remained until scientists were recently invited to make a formal examination of the specimen.

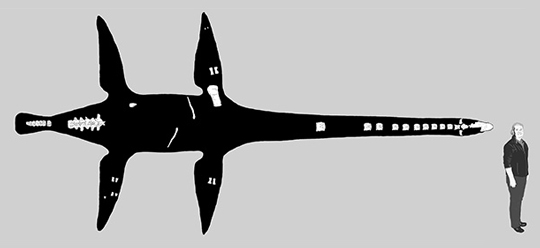

A Line Drawing of Lagenanectes richterae Showing the Known Fossil Material

Picture credit: Joschua Knuppe

Lead author of the study, Sven Sachs stated:

“It was an honour to be asked to research the mysterious Sarstedt plesiosaur skeleton. It has been one of the hidden jewels of the museum and even more importantly, it has turned out to be new to science.”

“Lagena Swimmer”

This basal elasmosaurid lived around 132 million years ago (Hauterivian faunal stage of the Lower Cretaceous), it has been named Lagenanectes richterae. The genus name is the Latinised form of the Leine River, which flows through the townscape of Sarstedt. The species name honours Dr Annette Richter, (Chief Curator of Natural Sciences at the Lower Saxony State Museum), who facilitated documentation of the fossil. Dr Richter also makes a handy scale reference in the drawing (above), L. richterae is estimated to have been around eight metres in length. The skull of Lagenanectes will be displayed as a centrepiece in the “Water Worlds” exhibition at the Lower Saxony State Museum.

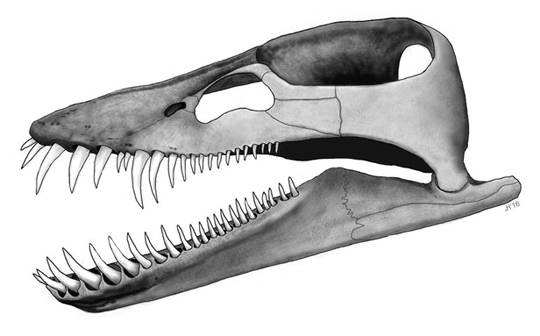

A Drawing of the Skull of L. richterae

Picture credit: Jahn Hornung

For models and replicas of marine reptiles including elasmosaurids: Models of Marine Reptiles and Other Prehistoric Animals.

Lagenanectes richterae

Co-author of the paper, Dr Jahn Hornung, a palaeontologist based in Hamburg said:

“Its broad chin was expanded into a massive jutting crest, and its lower teeth stuck out sideways. These probably served to trap small fish and squid that were then swallowed whole.”

Internal channels in the upper jaws might have housed nerves linked to pressure receptors or electroreceptors on the outside of the snout that would have helped Lagenanectes to locate its prey.

Bones at the back of the skull and the atlas show evidence of a chronic bacterial infection (osteomyelitic infection). This pathology is clearly visible in the fossil bones and this infection could have eventually claimed the animal’s life.

Dr Benjamin Kear (Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Sweden), who also contributed to the study, explained the significance of this Plesiosaur specimen:

“The most important aspect of this new plesiosaur is that it is amongst the oldest of its kind. It is one of the earliest elasmosaurs, an extremely successful group of globally distributed plesiosaurs that seem to have had their evolutionary origins in the seas that once inundated Western Europe.”

To read the earlier article chronicling the work of Sven Sachs in relation to the largest specimen of Ichthyosaurus described to date: Palaeontologists and the Pregnant Ichthyosaurus.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.