Seed Clue to How Birds Survived the Cretaceous Extinction Event

The birds that are around today, might have the seed-eating habit of an ancestor to thank for enabling their kind to survive the extinction event that saw the demise of the dinosaurs. A study published in the scientific journal “Current Biology” suggests that whilst the meat-eating and insectivorous feathered Maniraptoran dinosaurs did not survive into the Tertiary, toothless, beaked birds may have coped with the devastation that wiped out 70% of all terrestrial vertebrates, by eating seeds.

Seed Eating a Key to Survival

The study, conducted by scientists from the University of Toronto and the Royal Ontario Museum, involved the analysis of 3,104 Maniraptoran fossil teeth from eighteen different sites in western North America (Montana, USA and Alberta, Canada).

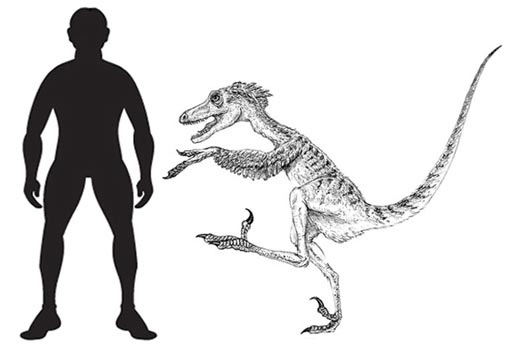

Late Cretaceous North America – Survival of the Seed Eaters?

Study suggests the evolution of a toothless beak ideal for seed eating may have had evolutionary advantages at the end of the Cretaceous.

Picture credit: Danielle Dufault

Seed Eating Birds

The beautiful illustration above, depicts an imaginary scene in the forests of Late Cretaceous North American (Maastrichtian faunal stage). There were probably large numbers of Maniraptoran dinosaurs represented by numerous families but these types of dinosaur along with the toothed birds did not survive the End Cretaceous mass extinction. Those members of the Maniraptora clade that had evolved an edentulous (toothless) beak capable of holding, manipulating and cracking seeds may have had an evolutionary advantage.

In the picture above, a large dromaeosaurid dinosaur pursues a toothed bird in the background, whilst a smaller dromaeosaurid pounces on an unsuspecting lizard resting on a log. Emerging from the hollow log is a hypothetical, toothless bird, closely related to the earliest modern birds.

A Nuclear Winter

Many scientists believe that after the extraterrestrial impact that marked the beginning of the end for the non-avian Dinosauria, the impact threw up huge amounts of dust and debris into the atmosphere. This would have blocked out sunlight, leading to a nuclear winter with plant populations (reliant on photosynthesis to make food), crashing. The loss of the plants led to a collapse of the entire food chain. The plant-eaters would have died out and once there were no carcases left to scavenge, the meat-eaters would have perished too.

This new paper is one of a number of recent studies that attempts to explain why some types of animals survived, whilst other, often closely related species did not.

Toothed Dromaeosaurs Faced Extinction

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The Maniraptora Fossil Record

The Maniraptora fossil record (dinosaurs and the birds) is very incomplete. The research team knew that they only had a limited number of fossils of Late Cretaceous Maniraptorans to examine and that in all likelihood there were many more species living towards the end of the Age of Dinosaurs than have been identified to date. In addition, there was very little direct evidence of fossil species surviving the extinction event. So to help unravel the puzzle as to why some animals died but their close relatives survived, the scientists examined the fossil record of isolated teeth.

Shed teeth tend to be more robust than the delicate and light bones of Maniraptorans and they are more numerous, so the research team had a more substantial data set to work with.

Seeds – A Readily Available Food Source

The team concluded that seeds would have survived the global devastation that occurred. Seeds already in the ground would have been available as a food source for anything with a beak capable of eating them.

Commenting on why some animals survived whilst others went extinct, lead researcher, Derek Larson (University of Toronto) explained:

“We came up with a hypothesis that it had something to do with diet. Looking at the diet of modern birds, we were able to reconstruct a hypothetical ancestral bird and what its likely diet would have been. What we are envisaging is a seed-eating bird, so you’d have a relatively short and robust, strong beak, which would be able to crush these seeds.”

In August 2014, Everything Dinosaur published a study which had been conducted by an international team of researchers that looked at the rapid evolution and diversification of the Maniraptora. These dinosaurs evolved very rapidly and probably made up a significant proportion of the terrestrial vertebrate fauna in a number of Late Cretaceous ecosystems.

The Evolution of the Maniraptora

To read more about the rapid evolution of the Maniraptora: Downsizing Dinosaurs the Key to Survival.

The challenge to palaeontologists is to find fossil evidence of seed-eating birds being prevalent prior to the End Cretaceous extinction event and then evidence of radiation and diversification in strata laid down in younger sediments deposited beyond the famous K-T extinction boundary.

What About the Mammals?

This very interesting piece of research raises a number of other questions. For example, a number of Cretaceous small mammals would also have very probably eaten seeds, just like many kinds of small mammals do today. Could seed-eating also have helped several different types of mammal survive the extinction event? Given the success of the Maniraptora and their diversity it seems peculiar that no member of the Dinosauria evolved to take advantage of seeds as a source of food.

Many members of the Maniraptora were small, around the size of many seed-eating birds today, why weren’t these dinosaurs also able to take advantage of this food source to help them endure the nuclear winter?

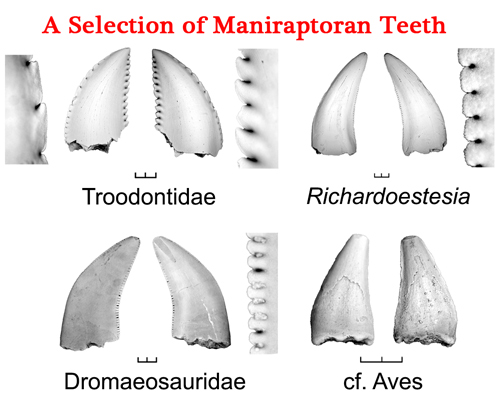

Teeth Representing a Variety of Different Members of the Maniraptora Were Studied

Picture credit: Royal Ontario Museum/University of Toronto with additional notation by Everything Dinosaur

Shed Teeth

The picture above shows a typical selection of the shed teeth used in the fossil study. Four different types of maniraptoran were incorporated into the study. Firstly, there were the Troodontidae, (top left) with their proportionately broader and much more prominent tooth serrations (denticles), an example of a typical Late Cretaceous North American Troodontidae would be Troodon inequalis. Secondly, there were members of the genus Richardoestesia (top right).

These maniraptoran dinosaurs are known from a pair of jawbones and many shed teeth, two species have been assigned, based on tooth differences. Then there are the dromaeosaurids (Dromaeosauridae). The teeth tend to be much more finely serrated than troodontid teeth and a typical North American dromaeosaurid would have been the two-metre-long Saurornitholestes langstoni.

An Illustration of Saurornitholestes langstoni

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

For models and replicas of dromaeosaurids and other dinosaurs: Beasts of the Mesozoic Models.

Dinosaur and Bird Fossils

Even though only a handful of fossil bones ascribed to Aves (birds) have been found in places such as the Dinosaur Provincial Park (southern Alberta), those bones that have been discovered indicate that some volant (flying) birds as big as modern-day raptors existed during the Late Cretaceous. Many examples of teeth from toothed birds are known from the Dinosaur Provincial Park, and at least three types of Neornithine birds have been described.

This research, that examined maniraptoran teeth across the last 18 million years of the Cretaceous, supports the idea of a sudden extinction event and the survival of Neornithine lineages as a result of some forms having evolved to exploit seeds as a food source.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s website: Everything Dinosaur.

Are there any cases on record in which the matrix that encloses an appropriate fossil skeleton has been analysed to investigate whether or not there is an associated fossil seed content present in the area of matrix which may have enclosed the gut of the animal?

We have not worked on any such examples ourselves but given the robust nature of seeds and gastrolith presence in a number of specimens evidence of seed eating could have been identified in a number of prehistoric animals, including dinosaurs and Pterosaurs.