Pterosaur Jawbone Hints at Greater Diversification of Ornithocheirids in North America

The fossilised mandible of a flying reptile (pterosaur) is helping scientists to piece together a puzzle that has confused palaeontologists for generations. Pterosaurs, those winged reptiles, the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight, ruled the skies for much of the Mesozoic. From their Triassic origins; this group of reptiles rapidly diversified and although they began to decline in numbers towards the end of the Cretaceous, the last of their kind persisted to the very end of the Mesozoic.

Flying Reptile

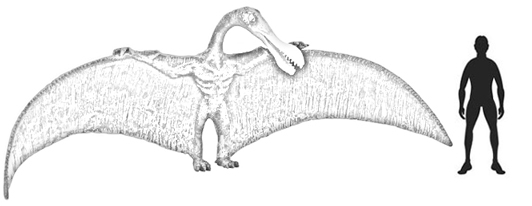

However, one particular family of pterosaurs, the Ornithocheiridae (the name means bird hand), despite being widespread and numerous were almost absent from the fossil record of Cretaceous North America. This omission had puzzled scientists. The Ornithocheiridae consist of a number of genera, fossils of which have been found in England, Europe, South America, Australia and Asia but to date only one fragmentary pterosaur fossil from the whole of North America has been ascribed to this particular family of flying reptiles. Most of these fossils date from the Early Cretaceous and some specimens represent species that may have rivalled the later Azhdarchidae as being the largest flying creatures ever. Ornithocheirus for example, a genus that represents ten species, may have had a wingspan in excess of 13 metres. However, the true size and diversity of this genus is difficult to assign accurately as the vast majority of pterosaur fossils relating to Ornithocheirus are fragmentary and poorly preserved.

However, the fossil finds of Ornithocheiridae in the whole of North America has just been doubled, thanks to the discovery of a 95-million-year-old jawbone. In a paper published in the scientific publication “The Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology”, the jawbone, discovered in Texas, four years ago is formerly described and a new genus of ornithocheirid announced. Enter Aetodactylus halli (the name means Hall’s eagle finger – after Lance Hall the amateur fossil hunter who found the fossil in 2006).

This pterosaur was very probably a fish-eater (indicated by dentition in the jawbone), it soared over what is now Dallas, approximately 95 million years ago (Cenomanian faunal stage). For much of the Cretaceous, North America was divided in two by a shallow sea (the Western Interior Seaway). It is likely that there were many ornithocheirids living at the time, but the geological conditions and their delicate, air-filled bones reduce the likelihood of fossil preservation. The jawbone indicates that this animal may have had a wingspan in excess of 3 metres.

A Scale Drawing of an Ornithocheirus

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

For replicas of ornithocheirids and other flying reptiles: CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Popular Range.

The fossil jawbone is compelling scientists to review the evidence for ornithocheirids in North America, commenting on the discovery Timothy Myers of Southern Methodist University’s Huffington Dept. of Earth Sciences stated:

“The fossil hints at a diversity of pterosaurs in the Cretaceous of North America that wasn’t previously realised.”

The only other North American pterosaur fossil ascribed to the Ornithocheiridae was discovered here, too, suggesting that the dearth of other ornithocheirids in North America might be more a function of geography and geology than actual biological distribution.

The press release describing the discovery of this new genus of flying reptile states:

“The ancient sea that covered Dallas provided the right conditions to preserve… the delicate bones of flying reptiles that fell from their flight to the waters below. The rocks and fossils here [Texas] record a time not well represented elsewhere in North America. That’s why two species of ornithocheirids have been found here but nowhere else, and that’s why discoveries of other new fossils are sure to be made….”

Lance Hall the amateur fossil collector who found the jawbone, discovered the specimen eroding out of an exposed piece of shale near a road southwest of Dallas. It seems likely that this animal’s body was swept out to sea, or perhaps it fell from the sky into the sea, sunk and was rapidly buried at the bottom in soft mud.

American scientists are hopeful that more fossils will be found in the strata, helping to shed further light on the diversity of Pterosaur genera in the region.

Leave A Comment