The Brain of Thecodontosaurus

Analysis of the brain and inner ear of the Late Triassic basal Sauropodomorpha Thecodontosaurus (T. antiquus), reveals that it may have been bipedal, able to hold a steady gaze whilst running and possibly predatory. These are some of the conclusions drawn by researchers from the University of Bristol and the Oxford University Museum of Natural History in a new study published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

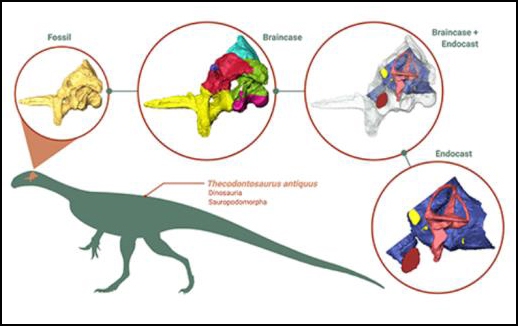

The Research Team Used CT-scans and 3-D Modelling to Construct the Brain and Inner Ear of Thecodontosaurus

Building up a picture of the brain and the inner ear based on the fossilised braincase of Thecodontosaurus antiquus.

Picture credit: Antonio Ballell et al

Thecodontosaurus antiquus

Named in 1836 (it was only the fourth dinosaur to be scientifically described), Thecodontosaurus is regarded as a basal member of the lizard-hipped Sauropodomorpha, a clade of dinosaurs that includes Brontosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Diplodocus and Argentinosaurus. Thecodontosaurus was much smaller than its illustrious Jurassic and Cretaceous descendants. It was approximately two metres long, more than half its body length was made up by its long, thin tail and it was lightly built with most palaeontologists estimating that it weighed around 20-25 kilograms, about as heavy as a border collie.

As an early member of the lineage of long-necked dinosaurs, a study of the fossilised remains of Thecodontosaurus can provide palaeontologists with a better understanding of the evolutionary history of the Sauropodomorpha.

For models and replicas of members of the Sauropodomorpha: CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Popular Figures.

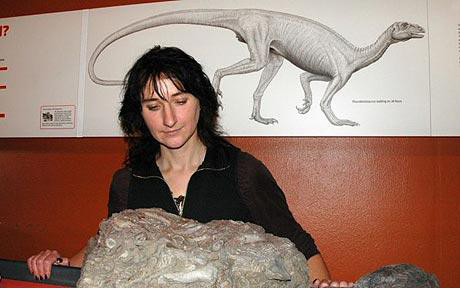

Bristol University has Researched the “Bristol Dinosaur” For Decades

Thecodontosaurus fossil block with life reconstruction in the background. In the picture (above), from 2009, a researcher stands in front of a block of Thecodontosaurus bones with a life reconstruction of the dinosaur in the background. Note that in 2009, Thecodontosaurus was thought to be quadrupedal, this new study suggests that it may have been bipedal.

Picture credit: Simon Powell/University of Bristol

Three-dimensional Modelling Techniques

Research, led by the University of Bristol, used advanced imaging and 3-D modelling techniques to digitally rebuild the brain of Thecodontosaurus. The scientists suggest that Thecodontosaurus could have eaten meat. Although the substantial part of its diet was plant matter, its brain morphology indicates that this little dinosaur had a good sense of balance and that it was agile. Traits that may have helped it supplement its vegetarian diet with the occasional meal of captured prey.

Lead author of the study, Antonio Ballell stated:

“Our analysis of Thecodontosaurus’ brain uncovered many fascinating features, some of which were quite surprising. Whereas its later relatives moved around ponderously on all fours, our findings suggest this species may have walked on two legs and been occasionally carnivorous.”

The research team was able to deploy imaging software to extract new information from the fossils in a non-destructive manner. Numerous three-dimensional models were generated from CT scans by digitally extracting the bone from the rock, identifying and classifying anatomical details about the brain and the inner ear which were previously unknown in this taxon.

PhD student Antonio explained the basis of the research:

“Even though the actual brain is long gone, the software allows us to recreate brain and inner ear shape via the dimensions of the cavities left behind. The braincase of Thecodontosaurus is beautifully preserved so we compared it to other dinosaurs, identifying common features and some that are specific to Thecodontosaurus. Its brain cast even showed the detail of the floccular lobes, located at the back of the brain, which are important for balance. Their large size indicate it was bipedal. This structure is also associated with the control of balance and eye and neck movements, suggesting Thecodontosaurus was relatively agile and could keep a stable gaze while moving fast.”

The Diet of Thecodontosaurus

The diet of Thecodontosaurus, nicknamed the “Bristol dinosaur” as a result of its association with the city, remains uncertain, although this new study suggests that it may have been omnivorous.

Antonio added:

“Our analysis showed parts of the brain associated with keeping the head stable and eyes and gaze steady during movement were well-developed. This could also mean Thecodontosaurus could occasionally catch prey, although its tooth morphology suggests plants were the main component of its diet. It’s possible it adopted omnivorous habits.”

The researchers were also able to reconstruct the inner ears, allowing them estimate how well it could hear compared to other dinosaurs. Its hearing frequency was relatively high, potentially inferring some sort of social complexity, an ability to recognise varied squeaks and honks from different animals.

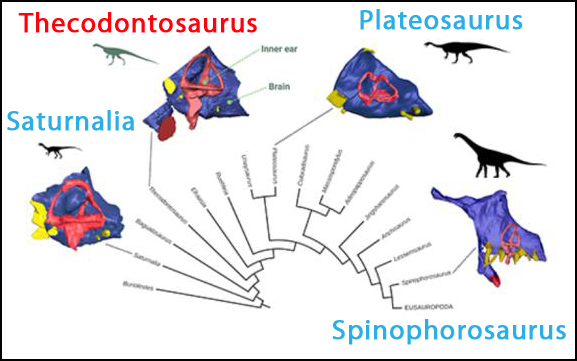

Comparing the Brain Cast of Thecodontosaurus to Other Dinosaurs

Structure, size and shape of the inner ear and brain examined in relation to the evolution of the Sauropodomorpha.

Picture credit: Antonio Ballell et al with additional notation by Everything Dinosaur

Comparing Thecodontosaurus to Other Members of the Sauropodomorpha

The application of these technologies enabled the research team to compare the brain and inner ear of Thecodontosaurus to Saturnalia tupiniquim – an earlier basal sauropodomorph which roamed the Southern Hemisphere around twenty-five million years before Thecodontosaurus evolved. Comparisons were also carried out between Plateosaurus, which is also known from the Late Triassic and the much later sauropod Spinophorosaurus (S. nigerensis) from the Middle Jurassic.

Professor Mike Benton, study co-author, said:

“It’s great to see how new technologies are allowing us to find out even more about how this little dinosaur lived more than 200 million years ago.”

The distinguished professor added:

“We began working on Thecodontosaurus in 1990, and it is the emblem of the Bristol Dinosaur Project. We’re very fortunate to have so many well-preserved fossils of such an important dinosaur here in Bristol. This has helped us understand many aspects of the biology of Thecodontosaurus, but there are still many questions about this species yet to be explored.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bristol in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “The braincase, brain and palaeobiology of the basal sauropodomorph dinosaur Thecodontosaurus antiquus” by A. Ballell, J. L. King, J. M. Neenan, E. J. Rayfield and M. J. Benton published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment