Sensitive Probe Feeding Pterosaurs

Whilst it is not always sensible to compare the Pterosauria to birds, they do have a number of things in common. As vertebrates they may not be very closely related but both birds and pterosaurs share some common anatomical characteristics that have helped them to conquer the sky. Their skeletons show special adaptations to assist with powered flight and if we focus on modern birds for a moment, we can see that many forms have evolved to occupy different niches in ecosystems. For example, some birds such as vultures and condors are primarily scavengers, whilst others are active predators (eagles, hawks and falcons).

Yet more are omnivores and some such as flamingos (filter feeders), swifts (aerial insect hunters) and hummingbirds (nectar feeders) occupy very specialist roles within food chains.

Studying the Beaks of the Pterosauria

Although the known fossil record of the Pterosauria probably grossly under-represents these flying reptiles, palaeontologists are becoming increasingly aware of the diversity of this enigmatic clade. Around 130 genera have been described, probably only a fraction of the total number of genera that evolved during their long history and recently a combination of fossil finds from Morocco in conjunction with a re-examination of fossils from a chalk pit near Maidstone in Kent (England), has led researchers to propose yet another environmental niche for pterosaurs.

Some pterosaurs evolved sensitive beaks that allowed them to probe sediments to help them find food just like many types of modern wading birds and members of the Aves such as the kiwi.

A Life Reconstruction of the Lonchodectid Lonchodraco giganteus Probing in the Mud to Find Food

Picture credit: Megan Jacobs (The University of Portsmouth)

Unusual Foramina in a Fossil Specimen

Researchers from the University of Portsmouth in collaboration with Dr Nicholas Longrich (University of Bath), took a close look at the fragmentary remains of the anterior of the rostrum (front of the jaws), of the pterosaur Lonchodraco giganteus (formerly referred to as Lonchodectes giganteus). These fossils had been found in a chalk pit, close to the village of Burham, near Maidstone, Kent. They were originally described as a species of Pterodactylus by the British naturalist James Scott Bowerbank in 1846.

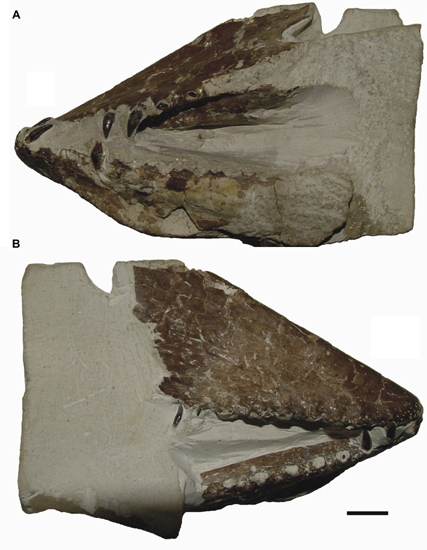

Lonchodraco giganteus Holotype Jaws

Picture credit: Martill et al (Cretaceous Research)

Extremely Fragmentary Pterosauria Fossil Remains

Like many pterosaur fossils from southern England, the fossilised remains are extremely scrappy, more recent studies have assigned these remains to the little-known lonchodectid pterosaurs (Lonchodectidae family). These types of pterosaurs are united by having low profile jaws, raised teeth sockets and uniformly small teeth.

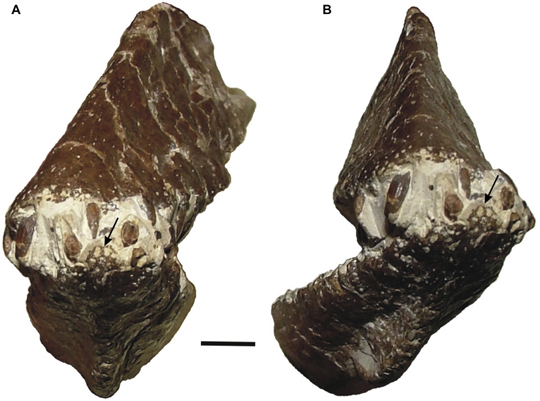

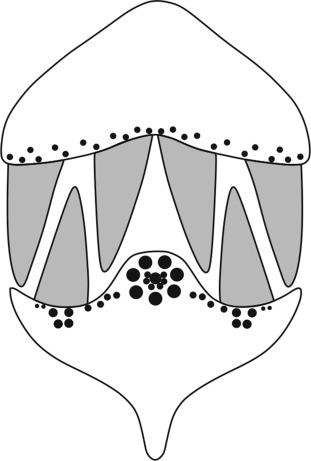

In a study of the holotype rostrum and mandible of L. giganteus, dozens of tiny holes (foramina) were discovered in the beak tip. These are thought to represent sensory areas on the beak, where nerves pass through the bone and make contact with the beak’s surface. Although foramina have been observed in the Pterosauria before, the pattern identified on the tip of the rostrum of Lonchodraco is unique.

Lonchodraco giganteus Holotype (Anterior View)

Picture credit: Martill et al (Cretaceous Research)

Identifying Nerve Clusters

These types of nerve clusters are reminiscent to those found in living birds such as kiwis, sandpapers, spoonbills, geese, ducks and snipes. These birds rely on their sense of touch when finding and catching food. Typically, they either probe in water, mud, sand or soil to locate and catch prey. This research, in combination with a second paper that also postulates on probe-feeding behaviour in the Pterosauria, suggests that just like modern birds, the pterosaurs were capable of evolving into a myriad of forms to exploit different food sources.

Concentration of Foramina at the Jaw Tips (Lonchodraco giganteus)

Picture credit: Martill et al (Cretaceous Research)

The scientific paper: “Evidence for tactile foraging in pterosaurs: a sensitive tip to the beak of Lonchodraco giganteus (Pterosauria, Lonchodectidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of southern England” by David M. Martill, Roy E. Smith, Nicholas Longrich and James Brown published in Cretaceous Research.

A Second Example of Probe Feeding

Recently, Professor David Martill, along with colleagues from Portsmouth University, pterosaur expert Samir Zouhri (Université Hassan II, Casablanca, Morocco) and Nicholas Longrich (University of Bath), published a paper in Cretaceous Research describing a new species of long-jawed pterosaur from Morocco that also could have been a probe feeder.

The flying reptile was described as having exceptionally long jaws for its body size, which terminated in a flattened beak with thickened bony walls. The shape of these jaws superficially resembled the beaks of probing birds such as kiwis, ibises and curlews. The research team hypothesised that like these living birds, this pterosaur probed in soft sediments in search of invertebrates. The age of the fossils is not certain, although an Albian to Cenomanian age was postulated. This pterosaur was tentatively assigned to the azhdarchoids, but if it is a member of the Azhdarchoidea, then it represents an extremely atypical form.

The scientists conclude that this Moroccan pterosaur adds to the remarkable diversity of the Pterosauria known from the Cretaceous.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of media releases from the University of Portsmouth and the University of Bath in compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “A long-billed, possible probe-feeding pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea: ?Azhdarchoidea) from the mid-Cretaceous of Morocco, North Africa” by Roy E. Smith, David M. Martill, Alexander Kao, Samir Zouhri, and Nicholas Longrich published in Cretaceous Research.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment