New Tetrapods from the Lower Carboniferous

Last spring Everything Dinosaur team members had the opportunity to travel to Edinburgh (Scotland), to view several early tetrapod fossils that had been excavated from a number of remarkable fossil sites located in the Scottish Borders. This week sees the publication of a scientific paper that describes five new tetrapods, helping to greater enrich our understanding with regards to the evolution and diversity of some of the very first vertebrates to adapt to terrestrial environments.

Scotland 355 Million Years Ago

Picture credit: Mark Witton/National Museums of Scotland

Scotland and Romer’s Gap

During the Late Devonian and into the Carboniferous, the area of land that makes up much of Scotland today was part of a giant super-continent called Laurentia. The Scottish Borders were located almost on the equator and the low-lying land was covered with some of the first large forests to evolve on Earth.

The climate was hot, humid and steamy, with seasonal flooding and also periods of intense drought. A team of scientists, that includes leading early tetrapod specialist Professor Jennifer Clack (Cambridge University), reporting in the academic journal “Nature Ecology & Evolution” describe five new Early Carboniferous tetrapods, helping to narrow a fifteen-million-year hole in the fossil record known as Romer’s Gap.

Fossils of Late Devonian tetrapods have been found, an example of which is Acanthostega, a stem tetrapod, fossils of Acanthostega have been found in Greenland, including fossil material found by Jennifer Clack. Acanthostega dates from around 365 million-years-ago, however, the next type of fossils found, date from rocks approximately 350 million-years-old and reveal animals with strong rib cages to support lungs and long, slender limbs – adaptations for a life on land. Harvard professor Alfred Sherwood Romer, was one of the first scientists to research early tetrapods and to identify this hole in the fossil record.

This fifteen-million-year interval became known as “Romer’s Gap”.

Professor Alfred Sherwood Romer (1894-1973)

Picture credit: Harvard University Archives

Five Almost Complete Fossils Plus Many Fragments of Bone

Building upon the early work of renowned Scottish palaeontologist Stan Wood and his co-worker Tim Smithson (Cambridge University), who, coincidentally, is also an author of this new paper, these researchers have identified a total of five new tetrapods from rocks laid down in the very Early Carboniferous (Tournaisian stage).

Although, isolated tetrapod limb bones dating from the Tournaisian faunal stage have been found outside of Scotland, most notably from the Horton Bluff Formation at Blue Beach, Nova Scotia (Canada), collecting from five Scottish locations has identified five new animals with at least seven other new taxa, that have yet to be fully studied.

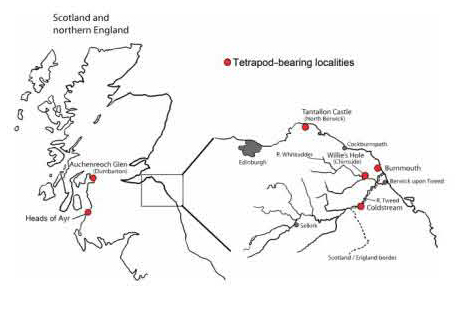

Tournaisian Tetrapod Fossil Collecting Locations (Scotland)

Picture credit: Nature Ecology & Evolution

This new research, which included exploring strata that today forms the bed of the River Whiteadder, a tributary of the River Tweed, has provided scientists with much more information about the diversity of early tetrapods and given them an insight into the fauna and flora that existed in some of the world’s first forests.

Bridging Romer’s Gap

The five new Tournaisian tetrapods named are:

- Perittodus apsconditus “concealed odd tooth”, known from the cheek region of the skull, lower jaw bones and postcranial elements found at Willie’s Hole on the River Whiteadder (Chirnside). The lower jaw measures a fraction under seven centimetres in length.

- Koilops herma “hollow-faced boundary marker”, the fossils consist of a natural mould of an isolated skull found at Willie’s Hole (River Whiteadder, Chirnside). The skull measures 8 centimetres long.

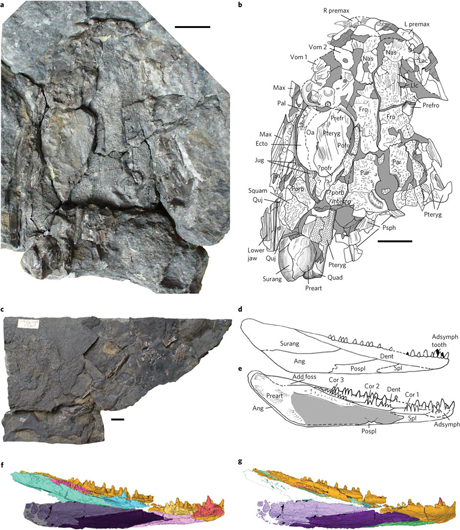

Two of the New Early Carboniferous Tetrapods (Perittodus apsconditus and Koilops herma)

Picture credit: Nature Evolution & Ecology

The photograph above shows (a) a photograph of the natural mould of the skull of K. herma with interpretative line drawing (b). Photograph of the main specimen block of Perittodus apsconditus (c), with reconstructions of the lower jaw (d-g).

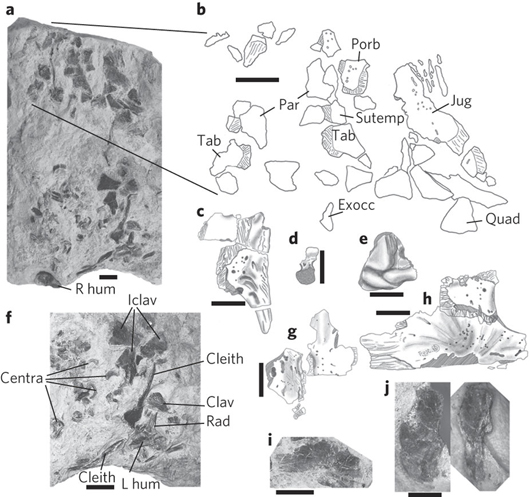

Fossils and Line Drawings of Ossirarus kierani

Picture credit: Nature Evolution & Ecology

Professor Clack et al Bridging Romer’s Gap

3. Ossirarus kierani “Kieran’s scattered bones” from Burnmouth Ross end cliffs (see picture above which shows photographs of the fossil material and line drawings). The species name honours the Kieran family who have done much to protect the natural habitat on this part of the Scottish coast. The taxon has been described from a single block of stone with preserved skull elements and postcranial bones. Ossirarus may have been a basal amniote, whilst the other four taxa named are classed as basal tetrapods.

4. Diploradus austiumensis “double row of teeth from the mouth of the river”, a reference to the strange configuration of the teeth in the lower jaw and the fact that the specimen, consisting of a single block of bones, was found at Burnmouth Ross end cliffs.

5. Aytonerpeton microps “small faced crawler from Ayton”, in reference to the size of the skull and the fossil find location (foreshore of Burnmouth Ross end cliffs heading towards the small village of Ayton).

Commenting on the significance of these new Scottish fossils, Professor Clack stated:

“We’re lifting the lid on a key part of the evolutionary story of life on land. What happened then affects everything that happens subsequently, so it affects the fact that we are here and which other animals live with us today.”

Charcoal Analysis

Sedimentary evidence analysis indicates that these early land animals lived on the low-lying land that was heavily forested, a sort of primeval, prehistoric swamp. This region was subject to frequent flooding, the fossils of various plants and invertebrates in conjunction with these exceedingly rare vertebrae specimens from locations such as Willie’s Hole are helping scientists to build up a picture of an Early Carboniferous palaeoenvironment – one of Scotland’s first wetlands.

It had been thought that atmospheric oxygen levels crashed during the Late Devonian/Early Carboniferous that inhibited the evolution of land-based vertebrates. A study of fusinite (fossil charcoal) collected from Willie’s Hole and the Burnmouth locations not only indicated that wildfires did occur, devastating local habitats, but chemical analysis revealed that oxygen levels did not drop below a level of around 16% in the atmosphere during the Tournaisian.

The scientists compared these results to fusinite samples taken from both younger and slightly older strata and they concluded that atmospheric oxygen levels were stable across the Devonian/Carboniferous boundary and therefore, probably did not inhibit the evolution of terrestrial vertebrates.

Everything Dinosaur Comments

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“It’s great to see more research being carried out in these Scottish locations, building on the work of field palaeontologists such as Stan Wood and we recognise the important role of the Natural Environment and Research Council for funding the study. The number of potential new taxa identified from the Scottish Borders raises the tantalising possibility that there are a lot more discoveries likely to be made in sedimentary rocks of a similar age.”

The scientific paper: “Phylogenetic and Environmental Context of a Tournaisian Tetrapod Fauna” published in the journal “Nature Ecology & Evolution”.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment