Unravelling the Mystery of an “Unravelling Ammonite”

Scientists from the Natural History Museum (Vienna) – Describe New Ammonite Species

Scientists at the Naturhistorisches Museum (Natural History Museum – Vienna) are helping to unravel the story of a bizarre new ammonite species that swam in the Early Cretaceous sea that covered what was to become the South Tyrol of Austria. Using advanced computerised tomography to create a three-dimensional image of the strange cephalopod, the researchers have been able to create a video showing how this animal swam. They have even discovered that this strange looking beast had a shell that was covered with sharp spikes, a deterrent against being eaten by the large marine reptiles that shared its underwater world.

New Ammonite Species

Ammonites are a group of marine, nektonic, cephalopod molluscs that lived in chambered shells. They were an extremely successful group with a huge number of different types and forms. The last of the ammonites died out at the same time as the dinosaurs (end of the Cretaceous).

Ammonite shell shapes varied considerably, shell shape often providing palaeontologists with an idea of how these animals lived, with each type of ammonite being adapted to a particular niche in a marine ecosystem. Most lay people would expect all ammonite shells to be coiled, this is not the case. During the Cretaceous, a number of ammonite families evolved bizarre shaped shells.

Some types of ammonite partially or nearly completely uncoiled, others uncoiled as they grew and then coiled up again as they reached maturity, others evolved screw-like spirals, superficially resembling the shell of a gastropod (snail).

Not All Ammonites had a Coiled Shell

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

A section of fossiliferous sedimentary strata high up on the Dolomites of the South Tyrol has yielded a number of beautifully preserved ammonite and other invertebrate fossils that researchers at the Natural History Museum (Vienna) have been able to study in fine detail. One particular specimen, a bizarre, uncoiled Ammonite, which represents a species unknown to science was subjected to intense examination using computerised tomography.

A three-dimensional image of the creature was built up by the scientists, layer by layer and this gave the team, led by Alexander Luke Eder (Department of Geology and Palaeontology), the chance to create a video depicting how this animal swam.

Fossil Slab

The fossil (slab and counter slab) was found at approximately 2,600 metres above sea-level in the Puez Park. The ammonite has been named Dissimilites intermedius and it lived in a warm, tropical sea that covered the South Tyrol approximately 128 million years ago. During the early Tertiary, plate movements in the Earth’s crust forced what was to become southern Europe to collide with the larger land mass that was to become northern Europe.

As the rocks crumpled and were pushed up due to the immense forces acting upon them, the Alps began to be formed. Sediment laid down at the bottom of a sea millions of years before, started to be elevated, and today Cretaceous-aged marine sediments can be found high up in the Dolomites mountain range.

Dissimilites intermedius Material Studied by the Scientists

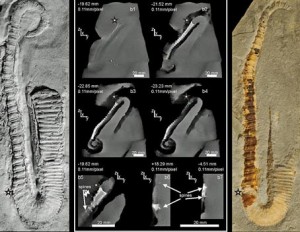

Picture credit: Natural History Museum (Vienna)/CEN/APA

The image above shows one of the slabs of rock with the uncoiled ammonite shell preserved, in the middle are images from the CT scans showing the composite structure of the ammonite. The specimen which is approximately thirteen centimetres in length, has provided scientists with the chance to study the fossils of this type of bizarrely-shelled cephalopod in great detail. The computerised tomography enabled the research team to build up a picture of the fossil in a non-destructive or intrusive manner.

The results of the Austrian team’s work have been published in the highly respected scientific publication – Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

The X-ray analysis revealed a surprise for the scientists. This particular ammonite seemed to have been a very spiky customer, armed with a series of three to four millimetre long spikes running almost the entire length of its shell. The animal would have lived in the last chamber of the shell to be formed, a the front of the shell (body chamber). The spikes probably served to protect this relatively small ammonite from being eaten. There were many types of marine reptiles – pliosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and plesiosaurs in the marine environment, most of these animals would have been capable of attacking and eating an ammonite of this size.

Dissimilites intermedius Brought Back to Life by the Austrian Scientists

Picture credit: APA/Natural History Museum (Vienna)/Alexander Luke Eder.

The research team were able to pinpoint how the organism fitted inside its body chamber. They were then able to speculate how it might have used its ten tentacles (presumed to have possessed ten tentacles, like other ammonites), to propel itself through the water with the aid of a directional water jet produced by a siphon positioned under the head.

As the creature would have only occupied the largest, last segment of the shell (body chamber), the scientists have pictured the smaller, walled-off shell chambers as being above the animal. This is because ammonites could manage their buoyancy by filling these chambers with gas. The smaller coil sections would therefore have been lighter and would have floated above the animal’s actual body.

The discovery of spikes on the specimen, may provide palaeontologists with a clue as to why so many uncoiled variants of ammonite shells evolved. Although some types of ammonite were strong swimmers, it is unlikely that they would have been able to swim faster than predatory fish, or even marine reptiles. With the evolution of Teleost fishes and the abundance of other marine predators, some types of ammonite may have evolved uncoiled shells as this permitted them to evolve more placement areas for spikes.

A coiled up shell has no opportunity to have spikes forming on the inner whorls as they are strongly attached to larger, outer whorls. An uncoiled shell, permits each whorl to have its own defences. Since fossil evidence shows coiled ammonites being attacked from behind (bite marks left in fossilised shells), having all round protective spikes makes evolutionary sense.

Using the information obtained from the three-dimensional scans, the Austrians were able to create a computer programme that modelled how this type of ammonite may have propelled itself about. From this, the team developed a short video reconstructing a scene from the Early Cretaceous of Austria showing a group of these floating molluscs at various growth stages, from juveniles to mature adults.

This video along with the fossil specimens of Dissimilites intermedius are on display at the Natural History Museum (Vienna, Austria).

To view a range of genuine ammonite fossils and replicas: Ammonite Replicas and Fossil Replicas.