Have we Got Evolutionary Trees All Wrong?

A study led by scientists at the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath suggests that a fundamental cornerstone of evolutionary biology could be misrepresenting taxonomic relationships.

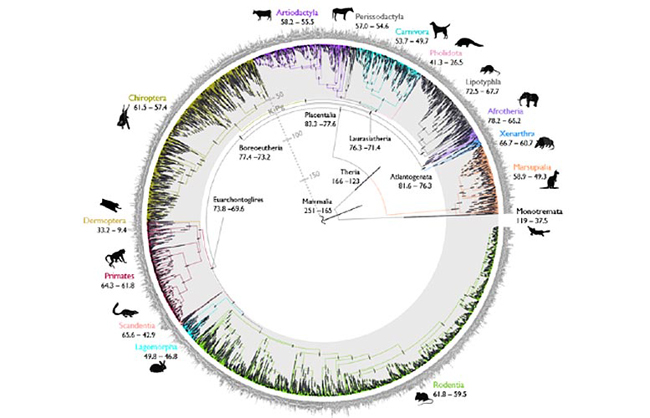

It is usual practice for biologists to establish evolutionary trees that set out the relationships between organisms. New research published in the academic journal “Communications Biology”, suggests that most of the evolutionary trees that have been constructed could be inaccurate and that convergent evolution is much more common than previously thought.

These trees are constructed by comparing anatomical characteristics, but this research suggests evolutionary trees based on the analysis of genetic sequences may be more reliable.

Overturning Centuries of Scholarly Work

Since Charles Darwin erected a “tree of life” in the 19th century, biologists have been trying to develop “family trees” of organisms by carefully examining differences in their anatomy and morphology.

With the development of rapid genetic sequencing techniques, scientists are now able to use genetic (molecular) data to compile evolutionary relationships very quickly and cheaply.

This genetic approach has led to substantial revisions in our understanding. Organisms once thought to be closely related have been demonstrated to belong to very different branches of the evolutionary tree.

Comparing the Two Methods of Building Evolutionary Trees

Scientists at the University of Bath compared evolutionary trees based on a traditional analysis of anatomy/morphology with those created using molecular data. The researchers discovered that the animals grouped together by molecular trees lived more closely together geographically than the animals grouped using the morphological trees, which implies that genetic themed evolutionary trees are more accurate.

Commenting on the significance of this study, one of the co-authors, Matthew Wills, Professor of Evolutionary Paleobiology at the Milner Centre for Evolution (University of Bath) explained:

“It turns out that we’ve got lots of our evolutionary trees wrong. For over a hundred years, we’ve been classifying organisms according to how they look and are put together anatomically, but molecular data often tells us a rather different story. Our study proves statistically that if you build an evolutionary tree of animals based on their molecular data, it often fits much better with their geographical distribution.”

Biogeography – A Reliable Guide to Evolutionary Relationships

Where organisms live, their biogeography, is regarded as an important source of evolutionary evidence that was familiar to 19th century scientists such as Darwin, Owen and Huxley. Genetic studies of animals that bear little similarity to each other such as aardvarks, elephants, golden moles, manatees and elephant shrews demonstrate that they originated from the same branch of the mammalian family tree. Molecular studies place these mammals into a single group called the Afrotheria, so-named because these animals seem to have originated from Africa, so the molecular data matches the biogeography.

Convergent Evolution More Prevalent

The study also found that convergent evolution was more prevalent than previously thought. Convergent evolution occurs when a trait or characteristic evolves separately in two genetically unrelated groups of organisms such as the evolution of tail flukes in cetaceans and the entirely unrelated ichthyosaurs.

Professor Wills added:

“We already have lots of famous examples of convergent evolution, such as flight evolving separately in birds, bats and insects, or complex camera eyes evolving separately in squid and humans. But now with molecular data, we can see that convergent evolution happens all the time, things we thought were closely related often turn out to be far apart on the tree of life.”

The ichthyosaur figure shown in the image above is from the Wild Safari Prehistoric World series.

To view this range of prehistoric animal models: Wild Safari Prehistoric World Figures.

The Professor explained that people who make a living as celebrity doubles or lookalikes are not usually related to the person that they are impersonating. Individuals in a family do not always look the same, it is the same for evolutionary trees.

Professor Wills stated:

“It proves that evolution just keeps on re-inventing things, coming up with a similar solution each time the problem is encountered in a different branch of the evolutionary tree. It means that convergent evolution has been fooling us, even the cleverest evolutionary biologists and anatomists for over a hundred years!”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bath in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Molecular phylogenies map to biogeography better than morphological ones” by Jack W. Oyston, Mark Wilkinson, Marcello Ruta and Matthew A. Wills published in Communications Biology.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.