If You Want to Live for a Long Time be Cold-blooded

Compared with most birds and mammals, reptiles like turtles and tortoises are extremely long-lived, but how do they achieve such great ages, with little evidence of age-related decline? Recently published research papers examined ageing rates and lifespans across seventy-seven species of reptiles and amphibians and these studies suggest that “cold-blooded” animals could teach us a thing or two about living to a ripe old age.

The Rebor 1:6 scale Pinta Island tortoise “Lonesome George” in oblique lateral view. Animals like giant tortoises are known to live to an extremely old age. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture (above) shows a 1:6 scale replica of a giant tortoise by the model manufacturer Rebor.

To view the range of Rebor models and figures: Rebor Models.

Life in the Slow Lane

An international team, consisting of over one hundred scientists including researchers from Flinders University (Adelaide, South Australia), Pennsylvania State, Northeastern Illinois University and the University of Kent, have provided the first comprehensive evidence confirming that turtles in the wild age very slowly and have long lifespans. In addition, the team concluded that reptiles and amphibians (ectotherms) have highly variable rates of ageing.

Several cold-blooded (ectothermic) species, essentially, do not age and show very little evidence for age-related decline. Unlike warm-blooded (endothermic) animals, ectotherms rely on external heat sources to help them regulate their body temperature, as a result, they tend to have much lower metabolisms than animals like birds and mammals. They way in which these animals regulate their body temperatures could play a role in ageing and potential lifespan (thermoregulatory mode hypothesis).

Native to Australia, the Sleepy lizard (Tiliqua rugosa), which is also referred to as the Shingleback, can live for more than 50 years. Scientists from Flinders University have been working on a long-term study of these slow-moving reptiles, their maximum age is not known. Picture credit: Mike Gardner.

Picture credit: Mike Gardner

Having a Shell, Armour, Venom or Spines Might Help You Live Longer

In this extensive study programme, the researchers also noted that animals with physical or chemical traits that provide defence and protection such as spines, armour, shells or venom, tend to age slowly and to live longer.

The scientists documented that these protective traits do, indeed, enable animals to age more slowly and in the case of physical protection, live much longer for their size than those without protective phenotypes (protective phenotypes hypothesis).

Some Cold-blooded Animals Do Not Seem to Age

Discussing the significance of this long-term research programme, Professor Mike Gardner (Flinders University) stated:

“We helped track seventy-seven species for up to sixty years to try to reveal the secrets of long life. Some don’t seem to age at all.”

First author of one of the studies, published in the journal “Science”, Assistant Professor Beth Reinke from Northeastern Illinois University added:

“These various protective mechanisms may reduce animals’ mortality rates within generations. Thus, they are more likely to live longer, and that can change the selection landscape across generations for the evolution of slower ageing. We found the biggest support for the protective phenotype hypothesis in turtles. Again, this demonstrates that turtles, as a group, are unique.”

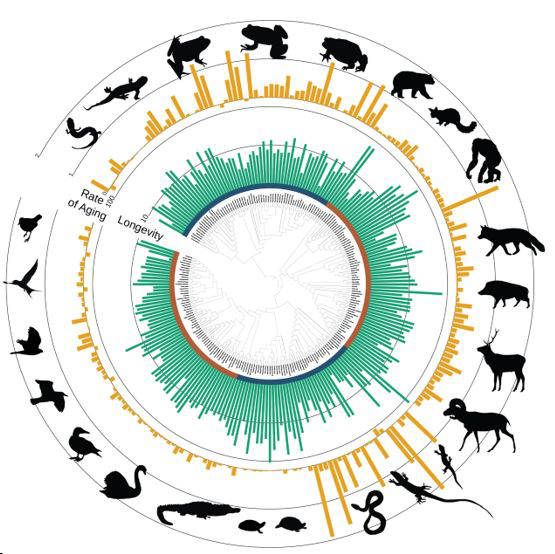

Ageing Diagram Ectotherms compared to Endotherms. A supertree diagram showing all the endothermic and ectothermic species included in the analysis. Branch lengths are not scaled. The red in the inner circle represents endotherms and blue represents ectotherms. Green bars are longevity estimates and orange bars are the aging rates. Silhouettes from Phylopic.org. Picture credit: Reinke et al.

Picture credit: Reinke et al

Cold-blooded

It might sound a little dramatic to conclude that some cold-blooded animals may show no signs of ageing, but basically their likelihood of dying does not alter to any great extent once they mature. They show “negligible ageing” which means if an animal’s chance of dying in a year when they are ten years old is 1%, if that animal is alive in a hundred years, it still has a 1% chance of dying.

In contrast, a study of American women found that the risk of dying at age twenty is 1 in 2,500, but this risk rises as they get older. For example, in this study group, at the age of eighty, their risk of dying was more than a hundred times higher (1 in 24) than when they were twenty years old.

Everything Dinosaur stocks a range of prehistoric reptile models including crocodilians and other cold-blooded animals as well as feathered dinosaurs and models of endothermic creatures.

To view the range: Models of Ectothermic and Endothermic Prehistoric Animals.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from Flinders University in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Diverse aging rates in ectothermic tetrapods provide insights for the evolution of aging and longevity” by Beth A. Reinke, Hugo Cayuela, Fredric J. Janzen et al published in Science.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.