DNA from Cave Sediments Reveals Ancient Human Occupants

Close to the Belgium town of Modave, there is a large cave. It overlooks the Hoyoux River, a tributary of the Meuse and although no human bones have ever been found at this cave site, palaeoanthropologists are confident that it was once occupied by ancient hominins as animal bones with stone tool cut marks are associated with the site.

The Trou Al’Wesse Cave

The cave is called Trou Al’Wesse (“Wasp Cave” in Walloon) and thanks to a remarkable application of technology, scientists now know that some fifty thousand years ago, a Neanderthal relieved himself inside the cave. That person’s urine and faeces may have long since decomposed but, left in the cave sediments were minute traces of his DNA. Researchers have shown that they can find and identify such genetic traces of ancient humans, enabling them to test for the presence of ancient hominins even at sites where no human bones have been discovered.

In addition, the same technique can be used to map other mammalian fauna at these locations. The scientists, including researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig, Germany) propose that this technique could become a standard tool in palaeoarchaeology.

Excavations at the site of El Sidrón, (Spain) – One of the Cave Sites in the Study

Picture credit: El Sidrón research team

The Secrets of Cave Soils and Sediments

Human remains are extremely rare and although scientists are aware of the existence of ancient hominins such as the Denisovans, they are only known from a handful of fossilised bones (literally, a single finger bone and a possible femur, plus some teeth). However, cave soils and sediments themselves can provide genetic evidence in the form of tiny traces of ancient hominin DNA. By examining cave soils and sediments and extracting genetic traces, scientists can gain a better understanding of the evolutionary history of humans, even if no bones or stone tools are present.

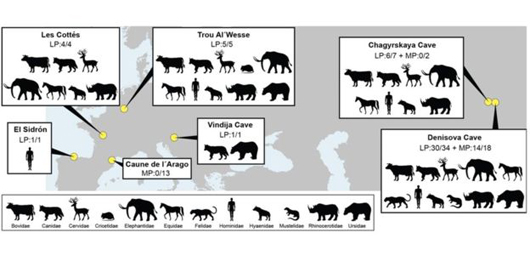

The research team members collected eighty-five sediment samples from seven caves in Europe and Russia that humans are known to have entered or even lived in during the Pleistocene Epoch. The samples dated from between 14,000 and 550,000 years ago. Using a refined DNA analysis technique, one that was originally designed to identify plant and animal DNA, the team were able to search specifically for hominin genetic evidence.

The Significance of this Research for Detecting Ancient Hominins

Commenting on the significance of this research, Matthias Meyer (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology) and co-author of the study published in the journal “Science” stated:

“We know that several components of sediments can bind DNA. We therefore decided to investigate whether hominin DNA may survive in sediments at archaeological sites known to have been occupied by ancient hominins.”

Entrance to the Archaeological Site of Vindija Cave, Croatia

Picture credit: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology/J.Krause

The picture above shows a view from the entrance of Vindija Cave in northern Croatia, one of the seven sites studied. Analysis of microscopic amounts of mitochondrial DNA at the Vindija Cave location confirmed the presence of several large mammals including Cave Bears at this location. The researchers found evidence of a total of twelve different mammalian families across the sites that were included in this study, including enigmatic, extinct species such as Woolly Mammoth, Woolly Rhinoceros and Cave Hyena.

Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA Helps Map the Presence of Large Mammals (Including Hominins)

Picture credit: Journal Science

Once animal DNA had been mapped the researchers turned their attention to identifying ancient human genetic traces within the samples.

Lead author of the research paper, PhD student Viviane Slon (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology), explained:

“From the preliminary results, we suspected that in most of our samples, DNA from other mammals was too abundant to detect small traces of human DNA. We then switched strategies and started targeting specifically DNA fragments of human origin.”

In total, nine samples from four cave sites contained enough ancient hominin DNA to permit further analysis. Of these, eight sediment samples contained Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA, either from one or multiple individuals, whilst one sample contained evidence of Denisovan DNA. The majority of these samples were taken from archaeological layers or sites where no Neanderthal bones or teeth had been previously found.

A New, Important Tool for Palaeoanthropology

Svante Pääbo, another co-author of the paper and director of the Evolutionary Genetics department at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology commented that the ability to retrieve ancient hominin DNA from sediments represented a significant advance in palaeoanthropology and archaeology. The use of this technique could become a standard analytical procedure in future.

A Sample Ready for Testing

Picture credit: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology/S. Tüpke

Even sediment samples that were stored at room temperature for years still yielded DNA. Analyses of these and of freshly-excavated sediment samples recovered from archaeological sites where no human remains are found will shed light on these sites’ former occupants and our joint genetic history.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the contribution of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in the compilation of this article.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment