The Dinosaurian Body Plan and Wonderful Alan Charig Remembered

Teleocrater rhadinus and Dr Alan Charig

There’s a book on our office shelves, its dust jacket is faded and torn and the pages are yellowed with age, not surprising really as it was printed in 1973. Although many of the passages, diagrams and ideas contained within it, have long since been superseded, it is treated with great reverence as it is one of the first dinosaur books I ever owned. Entitled “Before the Ark” it accompanied a ten-part television series on vertebrate palaeontology produced by the BBC.

Written by Alan Charig and Brenda Horsfield, (Dr Charig wrote and presented the television series too), it remains a treasured possession and today, with the publication of a scientific paper in the journal “Nature”, we remember Dr Charig, a man who is still having an influence on science, even though he passed away some twenty years ago.

“Before the Ark” and Teleocrater – Tribute to Dr Alan Charig

Picture credit: BBC with T. rhadinus artwork by Gabriel Lio (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales)

Early Dinosaur Counsin with “Crocodile-like” Appearance

Writing in the journal “Nature”, the researchers which include Sterling Nesbitt, assistant professor of geosciences at Virginia Tech, Roger Smith (University of Witwatersrand) and Paul Barrett of the Natural History Museum (London), describe more complete fossil material relating to Teleocrater rhadinus and formally establish this genus which helps to fill a critical gap in the fossil record leading to the evolution of the dinosaurs.

Teleocrater (the name means “slender complete basin” in reference to the reptile’s light build and the fully closed hip socket), was first proposed by Alan Charig back in the 1950s. He was a PhD student at Cambridge University writing a doctoral thesis on Triassic reptiles of Tanganyika (now Tanzania). Alan was being supervised by Francis Rex Parrington, a vertebrate palaeontologist who had uncovered the very first fossils of what we now refer to as Teleocrater rhadinus, during fieldwork in Tanganyika in 1933.

Fieldwork undertaken in 2015, led to the discovery of more fossil material and crucially limb elements and ankle bones which have helped determine where amongst the Archosaurs Teleocrater should be placed.

Team Members Extracting Fossil Material

Picture credit: Roger Smith

Published photographs show authors Christian Sidor (left), Sterling Nesbitt, Kenneth Angielczyk (in the purple top and white floppy hat), along with Michelle Stocker (right), looking for Triassic vertebrates in exposures of the Manda Beds (Anisian faunal stage of the Middle Triassic) of southern Tanzania.

All Fossil Material from the Manda Beds

Francis R. Parrington collected the first fossil specimens from the Manda Beds in the Ruhuhu Basin of southern Tanzania. These fossils were studied by Alan Charig for his doctorate, but much of Alan’s work on Teleocrater was never published. Dr Charig went to Tanzania to search for more fossils in 1963, but it was not until the expedition of 2015, that the crucially important limb and ankle bones were recovered that demonstrated where on the Archosauria family tree Teleocrater should sit.

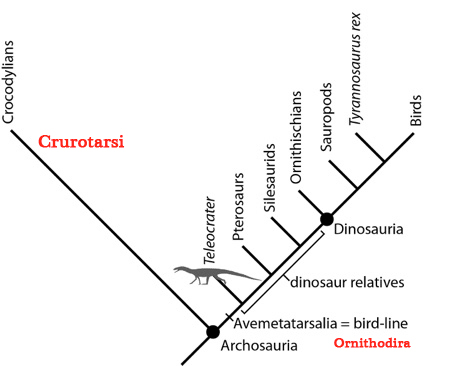

The ankle bones and other skeletal elements demonstrate that Teleocrater is more closely related to dinosaurs and birds than it is to crocodiles. It sits on the family tree of the archosaurs at the base of the Avemetatarsalian branch, the “bird-line Archosaurs”, sometimes also referred to as the Ornithodira. The researchers conclude that Teleocrater and its near relatives split off from other avemetatarsalians before the evolutionary split between the Pterosauria (flying reptiles) and the dinosaurs.

Establishing T. rhadinus on the Archosauria Family Tree

Teleocrater is more closely related to pterosaurs and dinosaurs (including birds) than to crocodilians.

Picture credit: Sterling Nesbitt of Virginia Tech with additional annotation by Everything Dinosaur

The Big Two Branches of the Archosauria

The Archosauria clade consists of birds and crocodiles plus an array of extinct creatures which include the dinosaurs, silesaurids and the flying reptiles (pterosaurs). This huge group of reptiles can be generally divided up into two distinct branches, based on the anatomy of the ankle bones. On one branch, we have the crocodiles and their relatives (Crurotarsi), which tend to have a sprawling gait, whilst on the other branch we have the Avemetatarsalia, otherwise referred to as the ornithodirans, which tend to have their limbs directly under their hips and have a more upright gait, similar to mammals.

Dr Charig never got the opportunity to study fossils of the ankle bone, he passed away in 1997, without being able to complete his assessment of this reptile. The researchers have honoured the contribution made by Alan Charig by naming him as an author on the 2017 paper and formally recognising the name Teleocrater, that he was the first to use.

Excavating the Fossils of Teleocrater

Picture credit: Roger Smith

Uniting the Aphanosauria Clade – Dinosaur Ancestors on All Fours

Teleocrater helps to cement the establishment of the Aphanosauria clade, a group of long-necked, slender-limbed, carnivores that lived in the Middle Triassic and were geographically widespread across Pangaea. The Crurotarsi archosaurs, those crocodile-like creatures were thought to be highly diversified and geographically widespread across the super-continent Pangaea. It now seems that the other branch of the Archosauria, the Avemetatarsalia, may have been equally as diverse and as widespread as their crocodile-like cousins.

Previously, palaeontologists have postulated that the earliest dinosaur relatives were chicken-sized and bipedal. Thanks to the 2015 fossil discoveries and the work first undertaken by F. R. Parrington and Alan Charig, scientists have a different body plan to consider. T. rhadinus which roamed the area that was to become Tanzania some 245 million-years-ago, was much larger at around three metres long and it was a quadruped.

An Illustration of the Early Avemetatarsalian Teleocrater rhadinus

Picture credit: Gabriel Lio (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales)

Remembering Dr Alan Charig

Alan Charig studied the fossils of what we now know as Teleocrater rhadinus. Twenty years after his death, scientists can place this enigmatic reptile and its relatives within the avemetatarsalian branch of the Archosauria, Teleocrater represents one of the earliest members of this sub-branch, a lineage that eventually led to the dinosaurs and the birds.

In addition, with a more complete picture of Teleocrater, palaeontologists have another puzzle to ponder. If the early branch members of the Avemetatarsalia were more species-rich and more widely geographically distributed than previously thought, then several early dinosauromorphs used to help scientists to understand how the body plan of the Dinosauria evolved, may represent specialised forms rather than the typical ancestral avemetatarsalian body plan.

Today, we reflect on the work of Dr Alan Charig and his mentor Francis Rex Parrington. The researchers writing in the journal “Nature” have helped to put flesh onto those bones first examined all those years ago. For my part, my thanks to Alan Charig for helping to write such a beautiful book and for inspiring a generation of science writers and enthusiasts.

The scientific paper: “The Earliest Bird-line Archosaurs and he Assembly of the Dinosaur Body Plan” by Sterling J. Nesbitt, Richard J. Butler, Martín D. Ezcurra, Paul M. Barrett, Michelle R. Stocker, Kenneth D. Angielczyk, Roger M. H. Smith, Christian A. Sidor, Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki, Andrey G. Sennikov & Alan J. Charig published in the journal “Nature”.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the help of Virginia Tech in the compilation of this article.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.