Didelphodon Study Suggests a Powerful Bite

Research published in the academic journal “Nature Communications” suggests that dinosaurs in the Late Cretaceous, did not have it all their own way when it came strong teeth and powerful jaws.

This new study, conducted by scientists from the Burke Museum and the University of Washington, indicates that the stem metatherian Didelphodon vorax may have had the strongest bite relative to its body size of any known mammal. The team estimate that D. vorax could have weighed in excess of five kilogrammes and probably would have attacked and consumed small dinosaurs.

However, microscopic analysis of the wear patterns on fossil teeth suggest that Didelphodon was not entirely carnivorous, it seems to have consumed a wide variety of food items including plants, but those robust jaws and specialised teeth were capable of crushing hard body parts such as the shells of snails and the bones of small dinosaurs.

Didelphodon with Durophagous Jaws

The research team suggest that Didelphodon may well have been durophagous (jaws and teeth adapted for crushing and coping with bones and other tough body parts, such as mollusc shells, bones and the exoskeletons of arthropods).

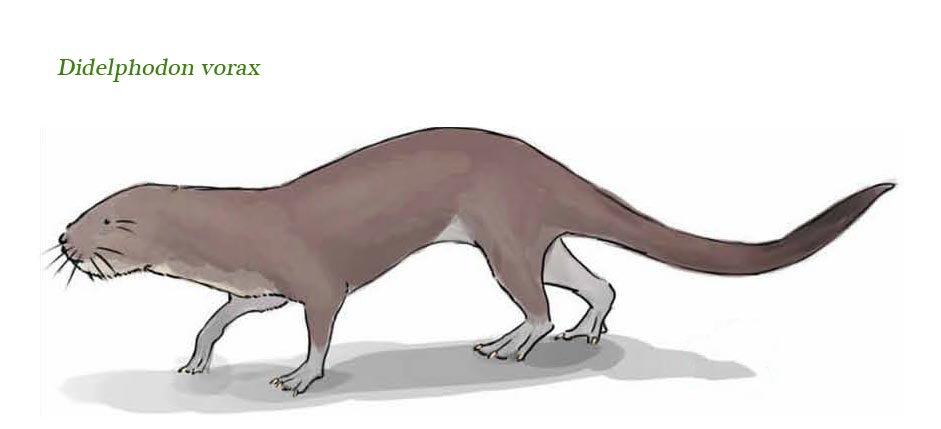

Didelphodon vorax Probably Ate Dinosaurs

Picture credit: Misaki Ouchida

Metatherians

Metatherians are the pouched mammals, the marsupials. Didelphodon is believed to be distantly related to extant marsupials such as kangaroos, koalas and opossums. Three genera have been named, all from fragmentary fossils found in North America. The Didelphodon genus was erected in 1889 by the distinguished American palaeontologist Othniel C. Marsh.

Ironically, it is very likely that small isolated bones and teeth representing many different types of Late Cretaceous mammal may have been overlooked by field teams working for Marsh as they strove to uncover large dinosaur bones in a bid to overshadow the exploits of Marsh’s bitter rival, Edward Drinker Cope.

Described as being roughly the size of a badger, but with the skull reminiscent of the extant marsupial the Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii), very little post-cranial Didelphodon material has been formally described. A specimen has been recently recovered from the Hell Creek Formation, it is likely that a more accurate picture of, what would have been one of the largest mammals of the Late Mesozoic, will emerge.

For the moment, there is a debate amongst palaeontologists as to whether Didelphodon was a semi-aquatic mammal with a lean, otter-like body or whether it was entirely terrestrial.

An Illustration of Didelphodon vorax

A Predator/Scavenger of the Hell Creek Formation

The research team, which included lead author, Dr Gregory Wilson (Burke Museum), examined four specimens from the Hell Creek Formation, namely a near complete skull, the most complete fossil skull of Didelphodon found to date, a partial snout and two upper jaw bones (maxillae).

All four specimens had been assigned to D. vorax based on an analysis of the cheek teeth that were present. These fossils enabled the team to estimate the strength of this mammal’s bite and the results, coupled with a study of teeth morphology, suggest that Didelphodon occupied a durophagous predator/scavenger niche in the Hell Creek ecosystem. Pound for pound, Didelphodon had a stronger bite than a Hyena!

For models and replicas of prehistoric animals from the Hell Creek Formation: PNSO Dinosaurs and Extinct Prehistoric Creatures.

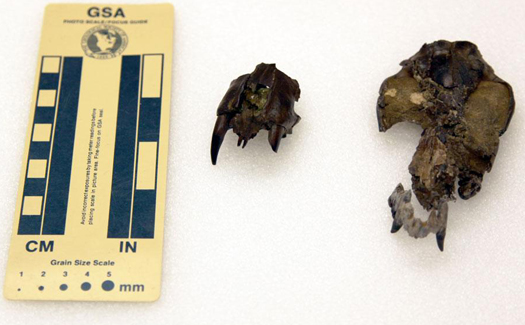

Some of the Fossil Specimens Used in the Study

The partial snout (UWBM 94084) and the near complete skull (NDGS 431) of Didelphodon used in the bite force study.

Picture credit: Burke Museum

Didelphodon vorax

Dr Wilson stated:

“What I love about Didelphodon vorax is that it crushes the classic mould of Mesozoic mammals. Instead of a shrew-like mammal meekly scurrying into the shadows of dinosaurs, this badger-sized mammal would have been a fearsome predator on the Late Cretaceous landscape – even for some dinosaurs.”

Most Cretaceous mammals are known from only isolated teeth and fragments of jaw. However, with a nearly complete skull, part of the North Dakota Geological Survey State fossil collection, the scientists were able to examine in more detail the phylogenetic relationship between Didelphodon and modern-day marsupials.

The team concluded that marsupials most probably evolved in North America, as part of a Late Cretaceous diversification of the Mammalia and later dispersed to South America. The Cretaceous extinction event that saw the demise of the Dinosauria and pterosaurs also resulted in the near extinction of the metatherian mammals.

These stem marsupials became larger and evolved to take advantage of different ecological niches before a decline in the North American metatherian diversity from the Late Campanian through to the Maastrichtian faunal stages of the Late Cretaceous, before these types of mammals died out almost entirely in North America at the end of the Mesozoic.

Marsupials survived in South America and marsupial diversity and evolution shifted to this part of the Americas.

A Closer View of the Snout of Didelphodon

A close up view of the snout of Didelphodon, one of four fossils used in a new study into Late Cretaceous metatherians.

Picture credit: Burke Museum

Marsupials from Hell Creek Formation

Marsupials seem to be the dominant types of mammal in the Hell Creek Formation, approximately sixty species have been described, Didelphodon being the largest. An analysis of the snout bones including the premaxilla suggests that this mammal had a highly mobile snout, a feature lost in most later metatherians.

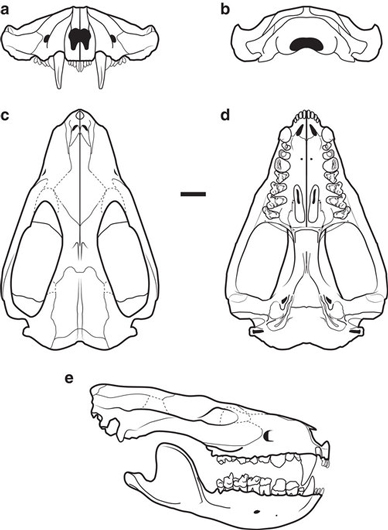

Fearsome Jaws and a Strong Skull (D. vorax)

Picture credit: Wilson et al (Nature Communications)

The picture above shows the reconstructed jaws and skull of D. vorax (scale bar = 1 cm). Picture (a) shows the anterior view (view from the front), whilst (b) shows the posterior view (view from the rear). A view from the top down (dorsal) is (c), whilst (d) is a drawing viewed from underneath (ventral view). Drawing (e), shows the skull and jaws as viewed from the right (right lateral view).

Although, these four specimens involved in the study have done much to improve our understanding of the skull morphology of Didelphodon, the areas not preserved in the actual fossils include the lower incisors, some upper incisors and parts of the back of the skull. Some suture lines remain unclear, these are shown in the above illustrations as dashed lines.

Commenting on the significance of this new insight into Late Cretaceous mammal evolution, Dr Wilson said:

“Our study highlights how, despite decades of palaeontology research, new fossil discoveries and new ways of analysing those fossils can still fundamentally impact how we view something as central to us as the evolution of our own clade, mammals.”

The scientific paper: “A Large Carnivorous Mammal from the Late Cretaceous and the North American Origin of Marsupials”, published in Nature Communications.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s award-winning website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment