Silurian Placoderm from China – a “Jaw-Dropping” Fossil Discovery

Say Hello to “Fish Face” Entelognathus primordialis – Crucial New Evidence into the Evolution of Jawed Vertebrates

The evolution of jaws was perhaps one of the most significant events in the history of the vertebrates (and this group includes us by the way). Jaws permitted vertebrates to eat bigger items, more diverse types of food, develop different feeding styles and in the case of fish, to push more oxygen bearing water through the expanded mouth cavity, a substantial aid to respiration. It can be argued that the development of a complex jaw gave the gnathostomes (jawed vertebrates) the edge over the invertebrates, perhaps most notably the arthropods and the Mollusca as these groups battled it out for the position of apex predators in the Palaeozoic seas.

The Evolution of Jaws

The discovery of cranial elements from an armoured fish at a quarry near to Xiaoxiang Reservoir, Yunnan Province, China, dated to approximately 419 million years ago is shedding new light on the evolution of jaws. This fossil shows the earliest evidence discovered to date of jaws and facial bones seen in gnathostomes. Other bones are more primitive, typical of a placoderm (armoured fish). This sets up the intriguing hypothesis that the face was the first modern skeletal feature to evolve.

The fish, which swam in shallow seas during the Silurian, has been named Entelognathus primordialis, the name means “primordial complete jaw”.

The beautifully preserved fossil skull shows details of the individual bones that make up the skull and jaws, its discovery is extremely significant as the placoderm group is believed to have given rise to the two major classes of extant fish, the cartilaginous fish such as sharks and rays which are known as Chondrichthyes and the bony fish, the Osteichthyes, which encompasses fish with bony skeletons and all other vertebrates that bear limbs with distinct digits, that’s amphibians, reptiles, mammals, birds and of course us. E. primordialis has dermal marginal jaw bones (premaxilla, maxilla and a dentary) and as such it is the first stem gnathostome to show such anatomical features.

Placoderms (Placodermi)

Placoderms (the name means plated skins) were primitive jawed fish. They are named after the broad, flat, bony plates that covered their heads and the front parts of their bodies. Although during the Silurian and up to the Middle Devonian this group was extremely diverse, this type of fish becomes increasingly rare in the fossil record from then onwards and it is believed that placoderms became extinct at the end of the Devonian around 360 million years ago. Features such as the braincase of E. primordialis indicate a strong affinity with the placoderms but, the pattern of the bones in the jaws is almost identical to that seen in fish of the class Osteichthyes and their descendants, terrestrial animals with backbones.

Silurian Placoderm

Member of the research team, Xiaobo Yu (Kean University in Union, New Jersey) commented:

“This is a unique pattern, that is found only in bony fishes. As such, finding the pattern in what otherwise looks like a placoderm is a real surprise.”

The Holotype Fossil Material with an Artist’s Impression of E. primordialis in the Background

Picture Credit: Reuters

Dermal Armour

The dermal armour at the front of placoderm bodies bears little resemblance to the skeletons of extant vertebrates. Scientists had thought that the descendants of the placoderms lost their dermal bones entirely with two main classes of fish evolving, the Chondrichthyes such as the sharks and the Osteichthyes. The sharks and rays continued to evolve without bony skeletons, these fish have skeletons supported by cartilage. The Osteichthyes class re-evolved the bony skeleton, a successful body plan of all bony fish and their descendants the tetrapods (amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals).

This new fossil find, is something of a smack in the mouth for the “second evolution” of the bony skeleton theory. The dermal plates of the placoderm may survive today in the jaws of gnathostomes, and that includes human beings as well. Placoderms may not have lost their dermal armour, it simply evolved into elements of the modern bony skeleton such as the upper and lower jaws. The face may have been the fist element of a modern gnathostome skeleton to evolve.

A Close up of the Fossil Material

Picture credit: Reuters with the mouth highlighted by Everything Dinosaur

Previously, the common perception had been that the sharks and rays with their skeletons made of cartilage were more primitive than the bony fishes. Their lack of a bony skeleton rather suggests that the Chondrichthyes arguably, have evolved further from the ancestral form than the bony fishes have. It may not be a case of having a cartilaginous skeleton being a primitive trait, this new discovery suggests that in terms of a support structure for their bodies, sharks and rays may be more different from basal forms than the bony fishes. Sharks and rays have evolved further from the ancestral, basal body structure.

A Computer Generated Image of the Fossil Material Revealing Skeletal Features

Picture credit: Nature

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur stated:

“This intriguing find, one of a number of Silurian fossil fishes that have been discovered in rocks making up the Kuanti Formation (Late Ludlow) Formation, might lead to a revision in the taxonomic relationships between basal members of the modern, vertebrate groups.”

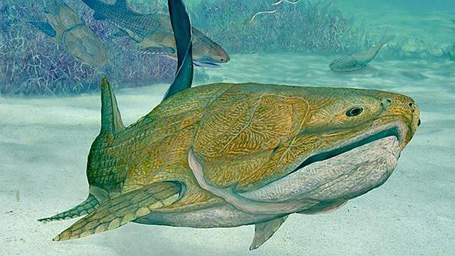

Life in the Silurian Seas – Entelognathus primordialis

Picture credit: Brian Choo

E. primordialis

The illustration above shows a life restoration of E. primordialis swimming in a warm, tropical sea that was to form the province of Yunnan (western China). Scientists believe that this fossil discovery re-writes the history of the evolution of jaw bones, including our own.

The scientific paper: “A Silurian placoderm with osteichthyan-like marginal jaw bones” by Min Zhu, Xiaobo Yu, Per Erik Ahlberg, Brian Choo, Jing Lu, Tuo Qiao, Qingming Qu, Wenjin Zhao, Liantao Jia, Henning Blom and You’an Zhu published in the journal Nature.