Did Birds out compete the Pterosaurs and force them to Extinction?

We have been recently reviewing some papers on Late Cretaceous pterosaurs written by Phil Currie and Stephen Godfrey. The papers refer to the examination of flying reptile finds in the Dinosaur Park Formation (DPF) of Alberta, Canada. Phil is the curator of Dinosaurs at the nearby Royal Tyrrell museum and Stephen works in the department of Palaeontology at the Calvert Marine museum. Much of these authors work has been condensed and reproduced in the excellent volume “Dinosaur Provincial Park”. This provides a review of the finds from this area and attempts to reconstruct the ecosystem that existed in this part of the world during the Campanian (rocks aged between 76.5 mya and 74.8 mya in the DPF).

Pterosaurs

Despite this being an area rich in fossils, there are very few remains of pterosaurs. Pterosaur bones are thin-walled and full of air cavities. This makes them light, ideal for flying creatures, however, they do not preserve very well. The fossil record for pterosaurs from this region is poor and only a few isolated large bones such as femurs, tibias (leg bones); and an ulna (arm bone) have been found, plus some phalanxes. The phalanx bones are the digits and in the case of flying reptiles these formed the wings.

From the limited evidence the scientists have been able to note that the vast majority of the remains seem to belong to a group of pterosaurs called azhdarchids. These were the extremely large flying reptiles, with long necks, rounded neck vertebrae and relatively long skulls. The largest flying reptile known – Quetzalcoatlus belonged to this family – the Azhdarchidae.

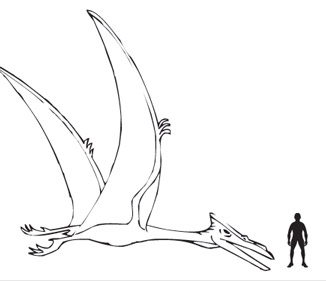

For a scale model of Quetzalcoatlus, the largest flying reptile yet described:

Pterosaur Models etc: Dinosaur and Prehistoric Animal Models.

End of the Cretaceous Flying Reptiles

It seems that the only flying reptiles left at the end of the Cretaceous were the extremely large, soaring types. We still don’t know how these animals lived, perhaps since many of the fossils have been found in marine sediments they were ocean going fish eaters that roosted on the tops of cliffs, like modern day gannets. It has even been suggested that Quetzalcoatlus was a specialist; feeding on crabs and other burrowing shellfish, using its long-snout to probe in the mud a bit like an oyster-catcher.

No skulls are known from the DPF so identification is difficult but it has been speculated that some of the remains belonged to Quetzalcoatlus northropi, the biggest pterosaur so far described. This would extend this animal’s range from Texas right up to northern Canada.

A Scale Drawing of Quetzalcoatlus northropi

Drawing courtesy of Everything Dinosaur

The Dinosaur Park Formation (DPF)

The DPF has also provided evidence of birds, although once again the fossil record is poor. Post cranial bones indicate that there might have been birds as big as modern hawks present in the Park area at the end of the Cretaceous. At least three types of neornithine birds have been reported. Neornithines have saddle shaped, articulating faces on their neck vertebra and usually lack teeth. These are effectively modern birds. As feathers tend to function better than flaps of skin, perhaps the birds dominated all the other aerial niches in the ecosystem and only the large soaring pterosaurs were left.

Birds do seem to have diversified very rapidly during the Cretaceous many modern genera that we would easily recognise were around in the last years of the dinosaurs. Evidence has been uncovered for owls, rails, cormorants and tern-like sea birds. Perhaps the rapidly expanding and diverse bird population led to the demise of the smaller pterosaurs.

To read an article from 2019 about a huge azhdarchid pterosaur discovered in Canada: The First Pterosaur Unique to Canada.

Or did the demise of small pteros free up ecospace which allowed the radiation of birds?? Solnhofen demonstrates sympatry between basal birds and small pterosaurs of roughly the same size. Haven't seen this blog before, glad to find you in the Boneyard!