An international team of researchers have published a ground-breaking study into bird evolution. This research is part of an extensive four-stage project that aims to provide a better understanding of the avian genetic pool. The study is associated with the Bird 10,000 Genomes (B10K) Consortium which aims to sequence the genomes of every single species of bird. It should help scientists resolve puzzles about evolutionary relationships.

Studying Bird Evolution

Approximately sixty-six million years ago, Earth experienced a mass extinction event. The impact of an extra-terrestrial bolide in what is now the Yucatan Peninsula (Mexico) caused ecosystems to collapse. Scientists estimate that more than three-quarters of all known species became extinct. The non-avian dinosaurs died out along with their pterosaur cousins. This extinction event is referred to as the Cretaceous-Palaeogene (K-Pg) extinction event. Fossil record data suggests that the vast majority of the world’s modern birds and mammals first appeared in the wake of that event, but further research was needed to clarify the origins of several clades.

The adaptability of many birds, such as their ability to consume seeds, a food resource that may have been relatively stable in the aftermath of the bolide impact, probably contributed to the survival of many lineages.

To read an article outlining research into avian survival: Seed-eating May Have Helped Some Birds Survive K-Pg Extinction Event.

Professor Peter Houde (New Mexico State University), is one of the fifty-two co-authors of this new study. It was published in the academic journal “Natural” earlier this year. The paper outlines what the authors discovered about bird evolution and relationships and explains how the new analysis compares to previous research. General relationships between birds, and those between species within specific families, have been extensively studied. However, where exactly many groups of birds sit in relation to each other has been surprisingly difficult to figure out.

For example, it had been thought that diurnal raptors like eagles and buzzards (Accipitriformes), were not closely related to owls (Strigiformes). However, this new study demonstrates that owls are a sister lineage to the Accipitriformes. That they are essentially nocturnal raptors.

Professor Peter Houde (New Mexico State University) highlighting the diversity of extant birds. He is one of fifty-two authors of a new study into the avian genome. Picture credit: New Mexico State University/Darren Phillips).

Picture credit: New Mexico State University/Darren Phillips

An Enormous Research Project

This new study represents phase two of the Bird 10,000 Genomes (B10K) project. Phase one, published in 2014, was ground-breaking both in its magnitude and in the data generated. The first part of the study sampled forty-eight species representing all orders of extant birds. Phase two was more ambitious. It involved three hundred and sixty-three species from ninety-two percent of all bird families. Moreover, phase two analysed fifty times more DNA per species. The dataset generated contained information on a hundred billion nucleotides.

Professor Houde explained:

“We’re only now beginning to understand how complex evolution is and to understand how biological processes work together to produce it.”

Complexity of bird evolution revealed by family-level genomes. The chart displays bird relationships and when groups diverged away from each other in deep geological time. Picture credit: Josefin Stiller, with paintings of birds by Jon Fjeldså.

Picture credit: Josefin Stiller and paintings of birds by Jon Fjeldså.

Scientists over the last two centuries inferred the relationships of birds and other organisms without the benefit of genetic data.

Professor Houde added:

“In the past, taxonomists who classified organisms were reliant on things like comparative anatomy and embryology and behaviour to infer relationships. It’s easy to see that a sparrow is close to a robin, but how might it be related to a duck? Are robins more closely related to ducks than they are to flamingos?”

Understanding Bird Evolution

Birds all ultimately descended from a single common ancestor. However, taxonomists argue about the evolutionary relationships between different lineages. Several competing and contrasting theories have been postulated. The scientific consensus states that a species can have only one closest relative. Yet, the conflicting hypotheses relating to taxonomy hinted otherwise. Is it possible that a species could be most closely related to two or more different lineages at the same time?

The “Proavis” model at the Grant Museum of Zoology (London). A model depicting a hypothetical ancestor of birds. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Researchers had a difficult time understanding how birds could seem to have multiple relationships at the same time. This research explains how this could come about. The genome is described as a “mosaic”. The genome of an organism is made up of mosaic pieces that have different evolutionary histories. It is likely that this pattern is related to biological processes that occurred early in bird evolution.

Birds are an extremely diverse group of animals. They can be found on every single continent, living in environments ranging from the driest desert to the ice and snow of the Poles. Within these habitats, they have further diversified to exploit a huge number of different niches. There are more species of birds known to science than species of mammals.

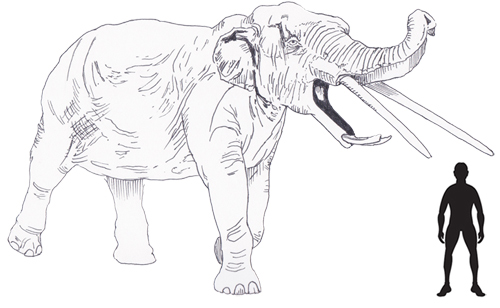

The research provides strong support for the idea that very few lineages of modern birds existed before and survived the K-Pg extinction event. The modern diversity of birds resulted from an explosive radiation of lineages immediately following it, as well as explosive population growth as birds expanded into vast newly uninhabited regions of the planet. This agrees with the fossil record but is contrasted by smaller studies. It is likely that the Aves were able to exploit the niches in ecosystems vacated by the extinct dinosaurs.

The Rise of the Elementaves

The study has led to the placing of a seemingly diverse group of birds in one new group. This group has been named the Elementaves as it includes specialists that are at home both in the water, on land and in the air. The Elementaves contains many species that you might expect to be closely related. For instance, penguins, albatrosses and pelicans. However, this group also includes other birds such as hummingbirds, swifts and the bizarre South American hoatzin. Therefore, the Elementaves contains the smallest and the largest volant birds.

Professor Houde opined:

“Furthermore, there are parts of the genome that are patently misrepresentative of what nearest relationships are. For example, you’ve got long-legged birds like storks, herons and cranes and so on and so forth. They all like to wade in water, yet they’re not each other’s nearest relatives. There are certain genes that they have, that have over millions and millions of years, allowed these birds to adapt to be able to wade in water. But those genes will mislead you about how those birds are actually related to one another.”

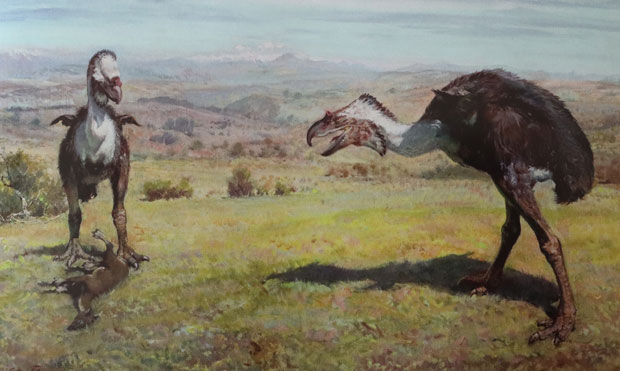

The closest related living birds to the “Terror Birds” (phorusrhacids), the Cariamiformes, are placed in a group entitled the Australaves uniting them with parrots, falcons and the order Passeriformes (the perching birds, which includes more than fifty percent of all known bird species). According to this research, they are far removed from other kinds of giant, flightless birds such as the ratites (ostrich, rhea, cassowary and emu). The cassowary and the emu are covered in hair-like feathers. It had been suggested that Cariamiformes such as Phorusrhacos longissimus may have possessed a hair-like integumentary covering. However, they were probably feathered like other Australaves, and their large size and similarity is the result of convergent evolution.

The Kelenken in all its glory. Cariamiformes were probably feathered unlike many large, flightless birds today that have a more bristle-like integumentary covering. Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Wider Implications for Taxonomic Studies

Houde and his colleagues used mathematical and probabilistic models to describe genetic connections more accurately and evaluate bird evolution. Although many of the assumptions on which scientists had based their standard models of bird evolution turned out to be true, co-authors discovered others were not valid. The Aves are an interesting group to study. However, this research can be applied to other organisms.

Although the results are not yet definitive, the authors’ new approach and findings will provide opportunities to enhance future research in this area.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from New Mexico State University in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Complexity of avian evolution revealed by family-level genomes” by Josefin Stiller, Shaohong Feng, Al-Aabid Chowdhury, Iker Rivas-González, David A. Duchêne, Qi Fang, Yuan Deng, Alexey Kozlov, Alexandros Stamatakis, Santiago Claramunt, Jacqueline M. T. Nguyen, Simon Y. W. Ho, Brant C. Faircloth, Julia Haag, Peter Houde, Joel Cracraft, Metin Balaban, Uyen Mai, Guangji Chen, Rongsheng Gao, Chengran Zhou, Yulong Xie, Zijian Huang, Zhen Cao, Guojie Zhang et al published in Nature.

The award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Dinosaur Toys and Models.